The United States, on 3 January, executed an unprecedented international intervention by conducting a military operation in Venezuela, which resulted in the removal of President Nicolás Maduro. Subsequently, he was extradited to the United States to face federal criminal charges, including allegations of drug trafficking. In the ensuing chaos, Delcy Rodríguez was appointed as interim president, as the nation grappled with deep political uncertainty and persistent economic challenges.

Diplomatic relations with the United States have undergone a significant transformation, with Washington indicating its intention to indefinitely oversee Venezuelan oil sales, including the management of revenue allocation to benefit the populace.

Venezuela is frequently characterised as a nation in crisis, with narratives of shortages, mass emigration, deteriorating public services and a weakened state dominating global media coverage. The prevailing explanation often attributes the situation to a sudden calamity, such as a sharp political shift, sanctions, or a series of recent policy errors that precipitated economic collapse. However, this simplistic framing is profoundly misleading.

The economic decline of Venezuela did not occur overnight; rather, it developed gradually over decades through stagnation rather than sudden shocks. The nation did not simply collapse; over more than four decades, it largely failed to achieve economic growth while the rest of South America progressed. The repercussions of this prolonged failure now shape the daily lives of millions of Venezuelans.

Four decades of stagnation

Economic crises are characterised by their dramatic nature, capturing attention due to their sudden and conspicuous onset. In contrast, economic stagnation is more insidious. When an economy fails to exhibit growth over extended periods, the resultant damage accumulates subtly: infrastructure remains outdated, skills become obsolete, capital depreciates, and institutions’ capacities diminish. Consequently, a society may not necessarily become poorer in absolute terms, but it experiences a relentless decline in relative wealth compared to the global context.

This phenomenon is exemplified by the economic trajectory of Venezuela over the past four decades. To understand this situation, it is essential to move beyond the immediacy of the present and consider the broader historical context of economic performance. The most reliable metric for assessing long-term living standards is GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP), a measure that reflects what people can actually purchase in their own economy.

By the early 1980s, Venezuela’s GDP per capita (PPP) approached $8,000, and, according to the recent data from the World Bank and IMF, it has remained within a similar range in real over subsequent decades. Various historical datasets indicate that, despite fluctuations, the country’s average income level in PPP has not experienced sustained growth since the late 20th century.

This pattern does not signify a temporary economic downturn; rather, it is indicative of an economy that has failed to develop.

Also read: What the US did in Venezuela shows the world is still at the mercy of brute power

A continent that grew, and a country that stood still

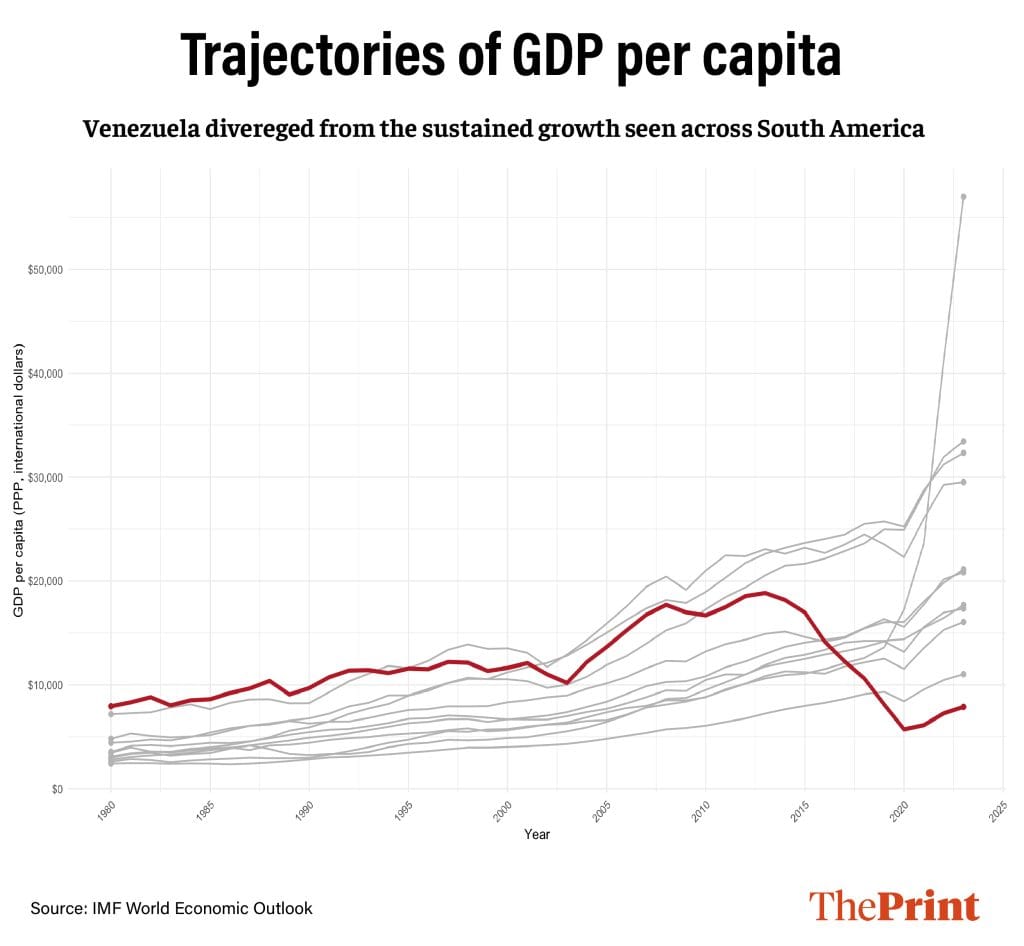

The extent of Venezuela’s economic stagnation becomes evident only through comparative analysis. Over the past four decades, the majority of South American nations have experienced a sustained increase in living standards; only Venezuela could not cope up.

The disparity is stark. In 1980, South American countries exhibited broadly similar income levels, with Venezuela ranking among the more affluent economies in the region. By 2023, this landscape had significantly altered. Chile, Uruguay and Argentina had advanced into high-income categories, while Brazil more than quadrupled its average income. Colombia, which initially lagged behind Venezuela, not only caught up but surpassed it. The region as a whole experienced upward mobility, whereas Venezuela remained stagnant.

Figure 1 accurately illustrates this divergence: while the majority of countries transition to different colours as they move to higher income brackets, Venezuela remains unchanged. Its relative position compared to its neighbouring countries exhibits minimal variations over a span of four decades. The time dimension makes the failure even harder to dismiss.

Figure 2 illustrates the trajectories of GDP per capita from 1980 to 2023. Across South America, the pattern is generally consistent, characterised by periods of volatility but demonstrating a clear upward trend over the long run. Venezuela’s trajectory diverges early and persistently. Its income increases during oil booms, subsequently stalls, and then reverses, never converging with regional counterparts.

The gap widens gradually, then decisively.

This comparison is significant as it eliminates simplistic explanations. Geography did not predetermine Venezuela’s fate, nor did culture, colonial legacy, or regional circumstances. Other countries facing similar external shocks, commodity cycles, and political constraints have managed to improve living standards over time, whereas Venezuela has not.

The distinction between stagnation and crisis is crucial. Economies can recover from recessions, even severe ones, but decades without growth erode the foundations of prosperity. When output per person fails to increase, wages stagnate, public services deteriorate, and opportunities diminish. Emigration becomes an economic necessity rather than a political choice. In this context, Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis is not an anomaly; it is the delayed consequence of prolonged economic erosion reaching its limit.

Also read: US invasion of Venezuela is end of international order. India must focus on cold calculations

Oil wealth failed to produce prosperity

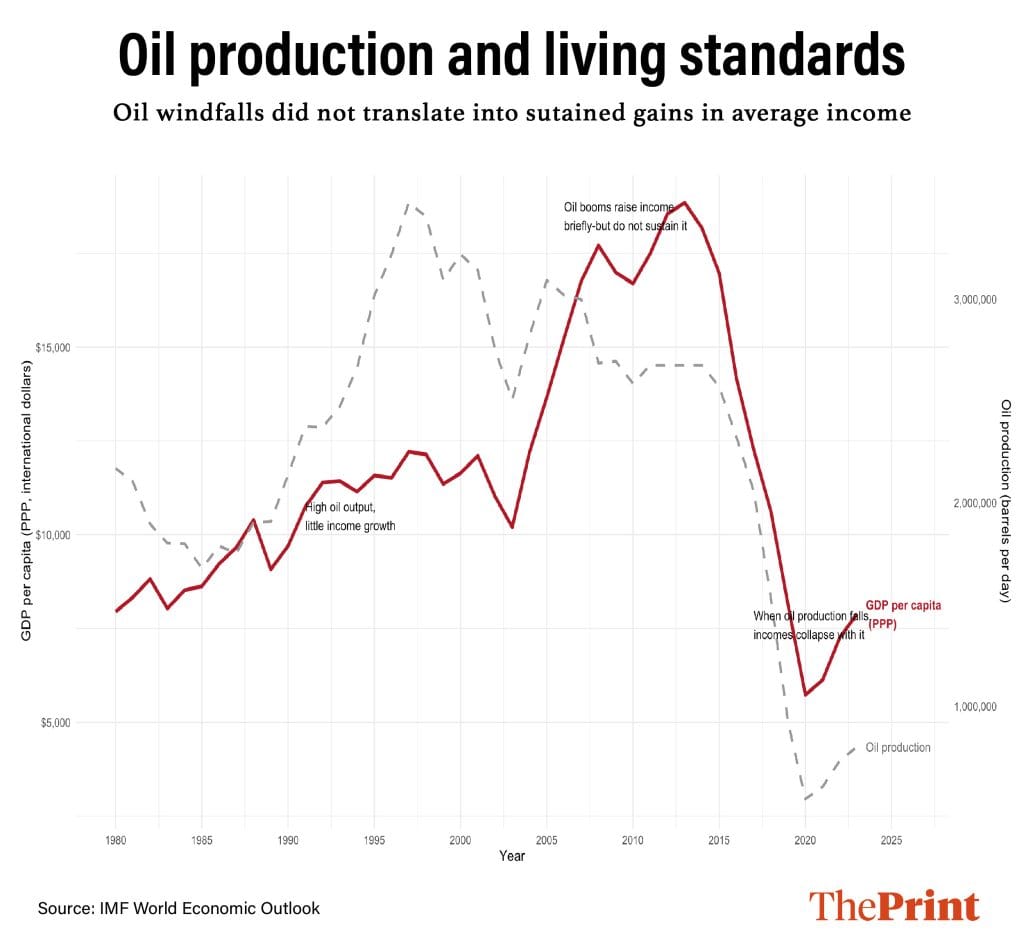

Venezuela’s situation is particularly due to the occurrence of economic stagnation in a nation possessing substantial natural resources. Specifically, Venezuela is home to the largest proven oil reserves globally, a resource that should have facilitated investment, economic diversification and increased productivity. However, this wealth instead supported a prolonged period of economic inertia.

Figure 3 makes the failure unmistakable. Oil production experienced significant increases throughout the 1990s and again during the mid-2000s economic boom. However, the resultant gains in average income were modest and short-lived. Living standards improved temporarily during periods of high output, only to stagnate and ultimately collapse without establishing a sustainable upward trajectory. The oil windfalls were consumed rather than being transformed into enduring growth.

Over time, reliance on a single volatile commodity intensified, while other sectors of the economy weakened. The ease of export revenues distorted incentives, crowded out non-oil activities and diminished the impetus to develop competitive institutions. Economists have long described this phenomenon as the resource curse: when abundance supplants discipline, long-term development falters.

Policy decisions compounded the damage. Price controls undermined domestic production, currency controls discouraged investment and fostered rent-seeking, and repeated expropriations deterred long-term capital formation. These decisions did not precipitate an immediate collapse; rather, they gradually eroded the economy, leaving it vulnerable when oil production eventually declined.

This perspective also clarifies the role of sanctions. While external pressures in recent years have intensified hardships, they cannot account for four decades of stagnation. Venezuela’s failure to converge with the rest of South America was entrenched long before the imposition of sanctions.

The implication of this lesson extends beyond the context of Venezuela. The mere possession of natural resources does not inherently guarantee economic prosperity. Redistribution efforts that lack a foundation in productivity fail to foster economic growth.

Furthermore, political narratives, regardless of their influence, cannot substitute for robust institutions that incentivise investment, innovation and sustained labour. Venezuela began this period with advantages that many nations would envy. It concluded this era having squandered an entire generation’s worth of economic progress – not through sudden collapse, but rather through the cumulative consequences of stagnation.

Bidisha Bhattacharya is an Associate Fellow, Chintan Research Foundation. She tweets @Bidishabh. Views are personal.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)