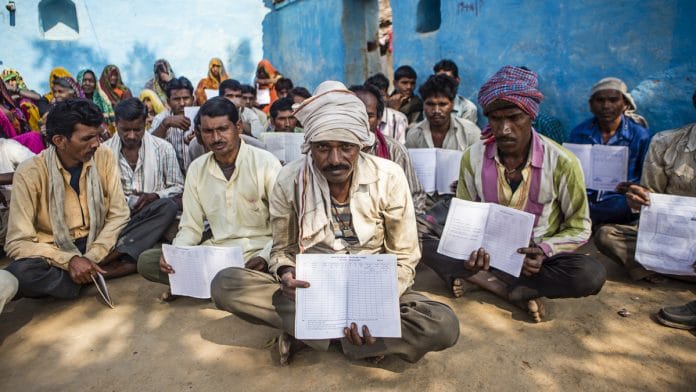

The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, or MGNREGA, was a constitutional departure in India’s welfare architecture. It transformed employment from a policy preference into a legal right.

Now that the Narendra Modi government has replaced this 2005 law with the Viksit Bharat – Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) Act, it is worth asking: how did MGNREGA actually perform in the last decade? And was it perceived as a failure because the idea was flawed, or because its legal and financial foundations were steadily weakened?

The under-funded programme

Since its inception in 2006-07, MGNREGA has always been demand-driven. When rural distress rises, demand for work goes up. When it falls, demand eases. This was broadly recognised during the UPA years (2006-13), when Budget Estimates and Revised Estimates usually followed actual demand.

That discipline broke down after 2014. Between 2015-16 and 2023-24, the government underestimated rural employment demand every single year. Revised Estimates exceeded Budget Estimates year after year, meaning that the programme was consistently under-funded on paper and patched up later. The Standing Committee on Rural Development and Panchayati Raj, in its 25th Report, flagged this mismatch, arguing that a demand-driven law cannot be run on optimistic or politically convenient budgeting. Those warnings were largely ignored.

Legal guarantees, unpaid in practice

Under MGNREGA, failure to provide work within 15 days mandated unemployment allowance; failure to pay wages within 15 days required compensation at 0.05 per cent per day of delay.

In 2024-25, 100 per cent of the unemployment allowance legally due remained unpaid in 13 states and Union Territories, including Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Manipur, Meghalaya, Punjab, Rajasthan, and Tamil Nadu.

At the all-India level, nearly 69 per cent of unemployment allowance due that year was never paid. The government simply did not honour the law.

Today’s budgets pay yesterday’s wages

Payment delays became normalised. In 2024-25, 2.2 per cent of India’s total unskilled wage expenditure under MGNREGA went toward clearing old wage liabilities.

Andaman and Nicobar Islands used 83.1 per cent of their unskilled wage expenditure to pay pending liabilities. The figure was 36 per cent in Manipur, 22.5 per cent in Meghalaya, 10.5 per cent in Puducherry, and 7 per cent in Haryana. Even large states such as Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Jammu and Kashmir, and Bihar diverted between 3 per cent and 5 per cent of wage budgets to arrears.

The imbalance is sharper when material and administrative expenditure is considered. At the all-India level, 37 per cent of cumulative expenditure on wages, materials and administrative work went toward paying liabilities from previous years, while spending on materials and administrative components was far more current. In Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Meghalaya, and Nagaland, this skew was extreme with 97 per cent, 88 per cent and 76 per cent, respectively.

Therefore, MGNREGA increasingly operated as a system where today’s budgets were used to pay yesterday’s bills, while legally mandated compensation for denied work remained unpaid.

Fewer households, longer work spells

Between 2014-15 and 2024-25, MGNREGA changed in a quiet but important way. Instead of reaching more households, it increasingly provided more days of work to fewer families. How this shift played out depended heavily on the social group.

Among Scheduled Caste (SC) households, the total volume of work increased, but access narrowed. The number of SC households that received work rose by about 19 per cent, while the number of person-days generated for SC workers jumped by nearly 60 per cent. More SC households also managed to complete the full 100 days of work. But this growth hides a concentration effect. Fewer SC families were being reached overall, even as those who did get work stayed on for longer. As a result, the share of SCs among households provided employment fell from 22.9 per cent to 19.5 per cent, and their share of total person-days declined from 22.6 per cent to 18.6 per cent. In short, work became deeper but less widely spread.

Scheduled Tribe (ST) households saw a different pattern. The number of ST households receiving work rose by over 34 per cent, and person-days for ST workers increased by an even sharper 93 per cent. The number of ST households completing 100 days more than doubled. Unlike SCs, STs slightly improved their relative position within the programme: their share among employed households rose from 17.2 per cent to 18.1 per cent, even though their share of total person-days dipped marginally.

The clearest and most consistent expansion was in women’s participation. The number of women workers increased by 41 per cent over the decade, rising from 312.6 lakh to 441 lakh. Women accounted for roughly 56 per cent of total person-days for most of the period, climbing to 58 per cent by 2024-25.

In practice, this meant that MGNREGA increasingly functioned as India’s largest public employment programme for women, even as its overall household coverage quietly narrowed.

When demand does not turn into work

Over the last decade, a growing gap opened up between people who asked for work under MGNREGA and those who actually got it. In 2014-15, the difference was about 1.9 lakh. By 2024-25, this gap had widened to 2.5 lakh households, averaging nearly 3 lakh households every year, with sharp spikes during 2018-19 and the Covid shock of 2020-21.

The more serious problem, however, lies elsewhere. The gap between households that demanded work and those that actually took up work was far larger. Between 2015-16 and 2023-24, this gap averaged around 1.4 crore households every year. The main constraint was not just whether work was offered, but whether it was worth taking up, given low wages, delayed payments, inconvenient timing, or worksites located far from home. In other words, demand existed, but the system simply failed to convert it into usable employment.

At the heart of this problem lies wages. Over the last decade, MGNREGA wages steadily lost ground, not just against market wages, but even against the government’s own minimum wage standards.

To begin with, workers often did not receive even the wages that states officially announced. Between 2015-16 and 2022-23, the average wage actually paid under MGNREGA was lower than the notified wage in every single year. Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Puducherry, and Gujarat saw this shortfall year after year. Underpayment was not a one-off glitch; it was routine.

More striking is how MGNREGA wages compare with legal minimum wages. Between 2014-15 and 2022-23, the average MGNREGA wage was below the central minimum wage for unskilled agricultural labour in every year. The gap widened sharply, from about Rs 46 per day in 2014-15 to Rs 176 per day by 2022-23. What was meant to be a statutory wage floor slipped well below the legal minimum.

Compared with market wages, the picture was no better. From 2015-16 to 2021-22, MGNREGA’s notified wages were consistently lower than prevailing rural market wages. When actual payments are considered, the gap is even wider. On average, MGNREGA workers earned Rs 77 less per day than market wages in 2014-15, and this shortfall grew to Rs 113 per day by 2021-22.

Finally, MGNREGA wages also fell below state minimum wages for agricultural labour. Between 2014–15 and 2019-20, the national gap widened from Rs 47 to Rs 163 per day, affecting almost all major states.

What expert committees warned

As far back as 2010, the Central Employment Guarantee Council reviewed several working group reports on the programme. One of the most influential—the Working Group on Wages, chaired by Jean Drèze—flagged a simple but serious problem: wages under NREGA were stagnating even as prices rose. Although the government had promised a real wage of Rs 100 per day, this figure was frozen in nominal terms. Inflation did the rest. Workers’ real earnings steadily eroded.

To prevent this, the committee recommended that NREGA wages be indexed to the Consumer Price Index for Agricultural Labourers (CPI-AL) from April 2009 onwards, so that the purchasing power of wages was protected over time. States that already paid higher wages were advised to continue indexing from those levels, with revisions every six to twelve months in line with inflation.

More importantly, the committee raised a deeper legal red flag. Until 2009, states were free to set NREGA wages. When the Centre froze state-wise wages and capped increases at Rs 100 per day, it activated Section 6(1) of the Act, allowing central wage notifications to override state minimum wages. In several states, this meant that NREGA wages could legally fall below the statutory minimum wage for agricultural labour. The working group warned that this directly undermined the Minimum Wages Act and insisted that NREGA wage policy must never undercut legally mandated minimum wages.

In 2013, the Mahendra Dev Committee pointed out that the Consumer Price Index for Agricultural Labourers (CPI-AL) was based on a 1986-87 base year and an even older 1983 consumption pattern. Rural consumption had changed radically since then, but wage indexation had not kept pace.

The committee argued that continuing to use outdated indices was leading to systematic underestimation of real living costs. It recommended updating the base years and, crucially, shifting to the Consumer Price Index for Rural (CPI-R), which better reflects contemporary rural consumption. Since MGNREGA applies to all rural households, not just agricultural labourers, the committee argued that CPI-R was the more appropriate benchmark.

It also proposed a clear safeguard: from 2014 onwards, MGNREGA wages should be indexed to whichever was higher—the prevailing state minimum wage for unskilled agricultural labour or the existing MGNREGA wage rate. This simple rule would have prevented wages from slipping below statutory floors.

In 2017, a committee chaired by Dr Nagesh Singh reiterated the case for shifting from CPI-AL to CPI-R. Despite the Ministry of Finance’s approval in early 2019, the process stalled. Inter-ministerial consultations dragged on. Base-year revisions became an excuse for delay. By October 2021, the government decided to retain CPI-AL after all.

The Standing Committee on Rural Development and Panchayati Raj questioned why workers under a centrally funded programme earn vastly different wages depending on where they live. At the time of its publication in 2023, MGNREGA wages ranged from Rs 193 to Rs 318 per day across states. It argued that a single, nationally applicable wage rate, revised annually, would simplify administration, reduce uncertainty for workers, and reinforce the programme’s welfare intent. The ministry’s defence was that wages are revised each year based on state-specific CPI-AL. The Committee found this explanation evasive and pressed for a serious examination of how a uniform wage could be designed without disadvantaging workers in any region.

Also read: Modi govt’s repeal of MGNREGA is all about extracting money from states, not reform

The risk of forgetting MGNREGA

MGNREGA was not perfect. But under VB–GRAMG, the danger is that the old law’s hard-won lessons — on demand-driven budgeting, gendered labour markets, wage floors, and federal accountability — will be lost in the promise of a “new” framework.

The last decade shows that rural employment demand remains structurally high, that women rely disproportionately on public works, that wages matter as much as days of work, and that statutory guarantees weaken when fiscal realism gives way to administrative discretion. Replacing MGNREGA without carrying these lessons forward risks repeating the same failures, only without the legal entitlements that allowed Parliament, courts, and workers to demand accountability.

The question, then, is not whether MGNREGA should evolve. It is whether VB–GRAMG will inherit its guarantees, or merely its vocabulary.

Priyank Nagpal is an Independent Researcher and a former LAMP fellow. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)