Technology, traditionally an enabler of high finance in the West, has been democratised in India. Finance, which was supposed to be a developmental economics tool, now sits firmly in the mobile phones of average citizens in the world’s most populous country. India is a case study of several innovations, from the world’s largest financial inclusion scheme and the world’s largest social security scheme to the world’s highest transacting economy. The Unified Payments Interface (UPI) binds these elements together.

UPI has become the world’s largest platform for payments—compared to Visa’s 639 million daily transactions in 2024, UPI recorded 644 million on 1 June 2025 and 650 million on 2 June. In terms of value of transactions, however, Visa still leads: at US$13.2 trillion, it is more than four times larger than UPI’s US$3.2 trillion. Considering that Visa was set up in 1958, almost five decades before UPI in 2016, this is unsurprising. Over the next decade, UPI volumes are expected to increase further, as it contributes to and partakes in India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth, currently the world’s fastest. Between May 2018 and May 2025, UPI payments doubled every year. Having reached critical mass, the momentum may slow down, but growth will nonetheless continue.

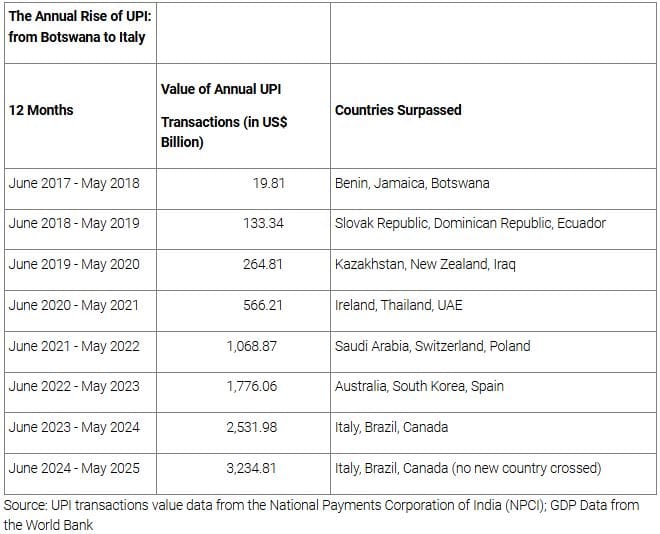

Viewed another way, the annual value of transactions on UPI (US$ 3.2 trillion) is greater than the GDPs of Italy (US$ 2.3 trillion), Brazil (US$ 2.2 trillion) or Canada (US$ 2.1 trillion)—see Table 1.

Table 1: The Annual Rise of UPI

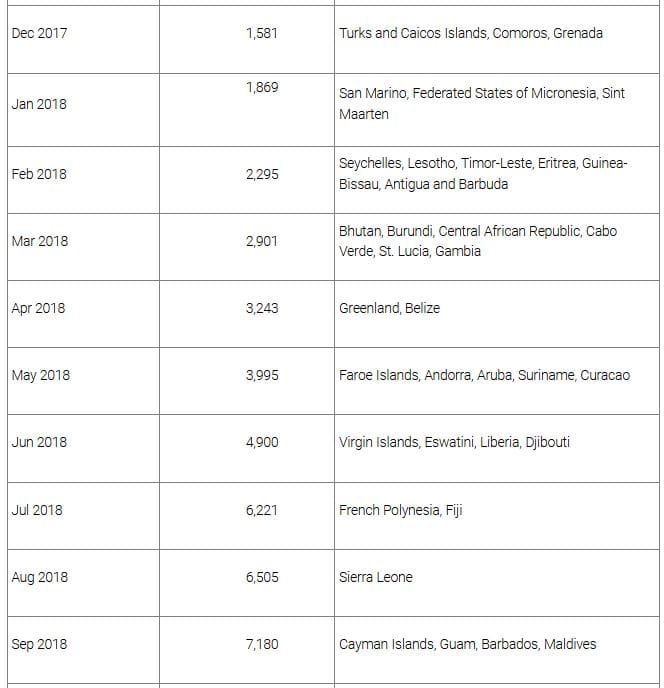

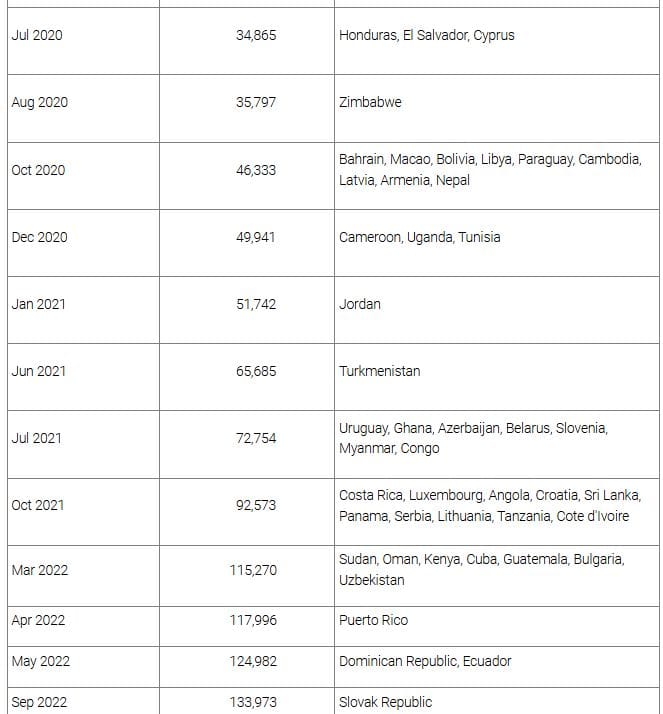

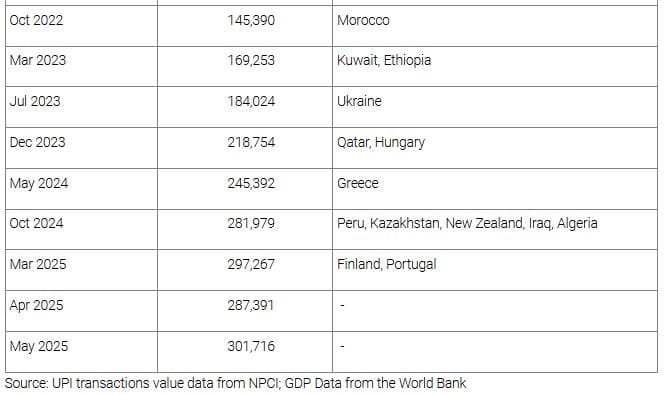

Examining it in another way, since its launch in December 2016, the value of transactions on UPI has added the equivalent of a country almost every month: it crossed Finland and Portugal in May 2025, New Zealand in October 2024, Greece in May 2024, Qatar and Hungary in December 2023—see Table 2.

Table 2: The Monthly Rise of UPI: From Tuvalu to Finland

The success of UPI rests on five pillars.

First, the demonetisation of INR 500 and INR 1,000 notes on 8 November 2016 created an urgency to seek out alternative transaction systems. Electronic payments became the go-to option. Taking demonetisation as a policy nudge, Indian citizens have shown a remarkable cultural flexibility in shifting from cash to electronic money. Today, cash is used more as a precautionary store-of-value than as a payment medium. The growth of cash has been slowing down, while that of digital has been rising.

Second, underlying the transactions was the digital embrace by Indians, led by the launch of Jio, which provided high-quality data at the world’s lowest prices, a strategy that other telecom companies soon followed. This led to the proliferation of smartphones, which enabled transactions.

Third, where internet connectivity is a problem, UPI functions on feature phones.

Fourth, unlike credit cards, there are no transaction costs on UPI. In a country like India, that’s a financial magnet.

And fifth, UPI is part of the government’s drive to deliver foundational digital systems through its digital public infrastructure push and employs Aadhaar’s identity infrastructure to integrate user data with the banking system.

Looking ahead, as an emerging supporter and an anchor of the Global South, India can use the UPI infrastructure as an international public good and an economic component of its grand strategy. This is a future that is presently being shaped: UPI is operational in seven countries outside India—UAE, Singapore, Bhutan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, France, and Mauritius. With France, UPI has entered the US$ 18 trillion European Union (EU) market; how it expands to the balance 26 countries—from Germany and Italy to Portugal and Malta—remains to be seen. Singapore has reached the US$ 4 trillion Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) market. Japan and Australia are the other digital destinations.

Also read: UPI redefining digital economy but govt coercion can stifle innovation

These aside, consider the developing economies of Asia, Africa and South America. UPI will work particularly well in geographies where the informal economy is large. Here, India will do well to replicate its complete basket of infrastructure—the JAM (Jan Dhan Yojana, Aadhaar, and Mobile ) trinity. This could mean offering not merely a UPI equivalent, but a JAM counterpart, with country-specific needs taken care of. This could involve advising or even building infrastructure around banking, identity and telecom, through government-to-government overseen public-private partnerships.

One country after another, one component at a time, the success of UPI must be leveraged to build new relationships with the world. The UPI can turn fineprint-free geoeconomics into a tool for geopolitics. A clear communication strategy powering the infrastructure is needed to engage with democracies across the world and build the goodwill of India’s soft power. The risk of giving in good faith but not receiving a return remains, as the recent experience of Türkiye shows. Yet for a rising power, it would be an adventure worth embarking on.

Given the strategic nature of financial infrastructure, especially at a time when everything from trade and technology to health and climate is being weaponised, India has the opportunity to operationalise what Prime Minister Narendra Modi has articulated through the idea Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam—the idea that the world is one family. Having achieved scale, the UPI can serve as a turning point in India’s engagement with a world that is collapsing under the weight of great power politics. The new world order needs India, and for India to count, it must, among other things, establish itself as a producer and dispenser of global public goods. Like vaccine diplomacy earlier, India must create and leverage UPI diplomacy as one strand of its emerging grand strategy.

Gautam Chikermane is Vice President at the Observer Research Foundation. Views are personal.

This article was originally published on the Observer Research Foundation website.