Is it fair to read the electoral outcome as a mandate against the BJP, the ruling establishment? One of us—Yogendra Yadav—has argued that is indeed the case. The NDA has the numbers to form the government, but the BJP has not only lost its majority, it has also failed to secure popular endorsement. The BJP may be the largest single party, way ahead of any rival, but its tally has to be seen against its own public target of 400+ seats and 50 per cent+ vote share. Above all, the electoral outcome has to be placed in the political context of how all the odds—money, media, governmental machine and even the Election Commission—were stacked against the Opposition in this election.

One possible counter to this reading is the story of BJP’s vote share, which has seen just a negligible drop from 37.4 per cent to 36.6 per cent. The BJP made a dramatic entry into Odisha, broke the Kerala barrier and improved its presence in Andhra and Punjab. It has an undeniable national footprint now, with a double-digit vote share across all the states of the Indian Union. The BJP advocates claim a victory based on these facts. Independent observers caution us against premature celebration and point out that the BJP’s reach has gotten deeper.

A closer look at the state-level vote shares shows that this is not the story of the political establishment losing in some areas and gaining in the rest. This was indeed a vote against the political establishment, except that the BJP did not represent the establishment everywhere. Let us think of two different BJPs that contested this election: BJP (Establishment) and BJP (Challenger). The Establishment suffered serious electoral reversals, while the Challenger had a good electoral outing. While the anti-establishment vote for the BJP in some states partially masked the national mandate against the BJP this time, this is a short-lived if not one-shot windfall that the ruling establishment cannot bank upon.

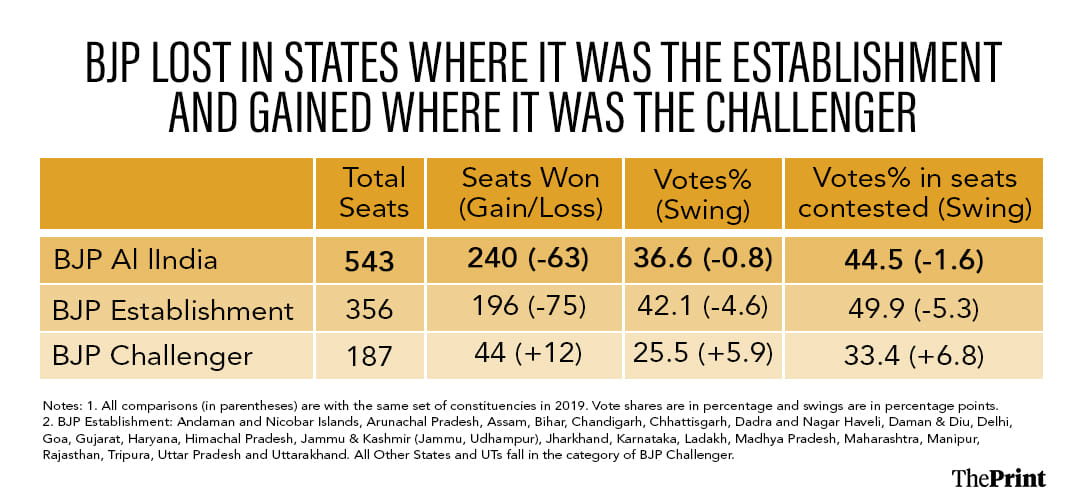

Let us look at the numbers presented in Table 1. In two-thirds of the country (356 seats to be precise) the BJP is the dominant political party even when it is not the state ruling party at the moment. This area stretches from Maharashtra and Gujarat to Bihar and Jharkhand in the east and includes states like Karnataka and Himachal where the BJP does not rule currently. In these states, the BJP Establishment faced severe electoral reversals to its near political monopoly, losing 75 of the 271 seats it held last time. On average, there was a five percentage point swing against the BJP in these areas that stretch from Karnataka to Bihar.

But in the remaining one-third of India (187 seats), the BJP entered this election as an anti-establishment force, a challenger to the incumbent or the dominant political party—BJD in Odisha, YSRCP in Andhra or TMC in Bengal. This BJP Challenger was a face-saver for the ruling party. The BJP gained 12 seats here over its tally in the last election. More importantly, it had a positive vote swing of about six percentage points, which contained the BJP’s national losses to under one percentage point of the vote share.

Also read: Why 2024 marks the return of state politics to the Centre

A serious setback

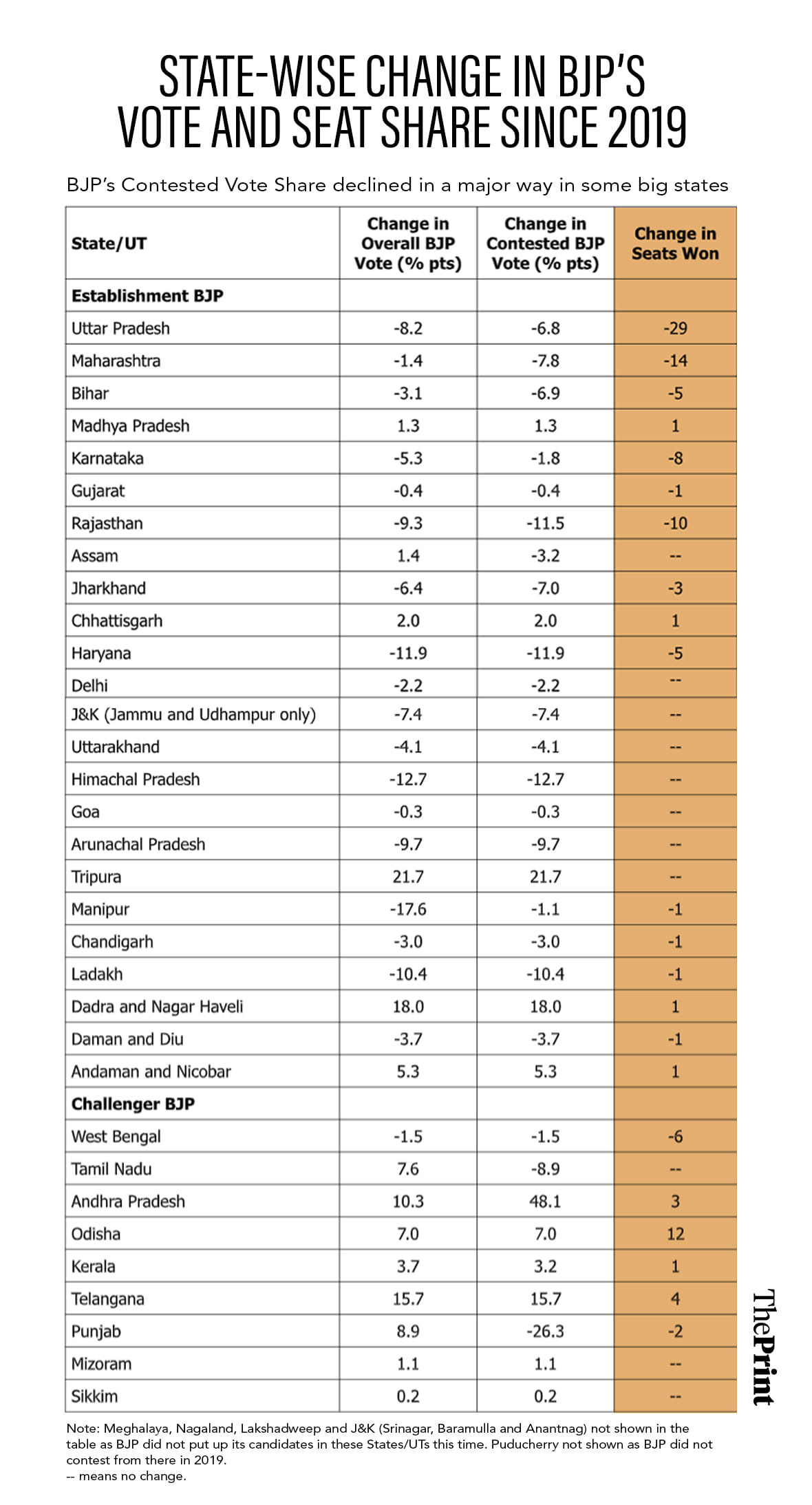

The BJP’s vote share is worse than it looks. Overall, the BJP’s vote share went down in 274 of the 399 constituencies that it contested both in 2019 and 2024. These included all the seats that the BJP contested in Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Bihar, Jharkhand, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir, and all but two seats in UP.

The margins of BJP victory went down sharply. The number of seats it won by 20 percentage points or more fell from 151 to just 77.

It is useful to see the swing in BJP votes in the 215 seats that witnessed a direct BJP vs Congress contest, seats where these two occupied the top two positions. Last time the BJP had won more than 90 per cent of such contests with an average margin of over 21 percentage points. This time the BJP won 153 of these seats, losing 62 to the Congress. The average margin was halved to a little less than 10 percentage points. Compared to 2019, these seats witnessed a negative swing of 5.5 percentage points against the BJP. That is indeed a serious setback.

If we look at the BJP Establishment states in Table 2, and focus on the BJP vote share in the seats it contested, we notice a negative swing that cuts across state boundaries. States like Rajasthan (12 per cent), Haryana (12 per cent) and Himachal (13 per cent) experienced the strongest double-digit anti-BJP swing. While the BJP’s earlier lead was huge in these states, the swing against it was concentrated in some areas in Rajasthan and Haryana (but not Himachal) for it to lose a substantial number of seats.

While the BJP’s dramatic losses in UP were the story of this election, it is interesting to note that the swing against the BJP is nearly identical in the neighbouring states of Uttar Pradesh (6.8 per cent), Bihar (6.9 per cent) and Jharkhand (7 per cent). In UP, the BJP had a smaller margin to defend and was up against a smart political and social alliance. But in Bihar, the BJP could cut its losses thanks to a huge (23 points) advantage that it began with and its ability to retain a very large coalition.

The smallest drop in BJP votes was in Karnataka, Assam, Delhi and Uttarakhand. In all these states the ruling party managed to retain most of its seats, except in Karnataka where the negative swing was concentrated in some regions that cost BJP many seats. The only exceptions to this story of negative swing for BJP Establishment are Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh where weak Opposition could not snatch any votes from the BJP.

We see the undercurrent in the opposite direction, though of varying degrees, when we look at BJP in the role of a Challenger. Here the sudden meltdown of, and indirect help from the BRS enabled BJP to add a whopping 15.7 per cent to its votes in Telangana, while an additional 7 per cent enabled the party to nearly sweep the Lok Sabha polls in Odisha. A modest but steady addition of 3 per cent votes helped the BJP pick its first Lok Sabha seat from Kerala.

In Tamil Nadu and Punjab, the loss of a key partner meant that the BJP lost the support of its former ally’s social base: its overall vote share did increase, as it contested more seats, but its vote share in the seats it contested decreased quite a bit.

West Bengal looks like an exception to this trend, as the BJP was very much a challenger but lost 1.3 per cent vote share in the state, failing to recover from the debacle in the Assembly elections.

The real question in this election was: would this political establishment secure a stamp of popular endorsement? No wonder, the election was all about the ambitious target that BJP set for itself—no less than 400+ seats and 50 per cent+ votes. It was an election that the BJP was widely believed to have won even before the schedule was announced. No one bothered about the tally of its opponents. Nor that of its allies. All that was incidental to the real power play around Modi and his party.

The real question for the future is: how long can the BJP Challenger rescue the BJP Establishment? This window appears very short both in terms of time and space. There are not many states now where the BJP has a headroom to grow. And this advantage may not continue for long. Sooner than later, the BJP Establishment has to find ways of not meeting the fate of the Congress Establishment, and that too when Modi’s charm is fading. This election may not give the BJP much confidence in this respect.

Yogendra Yadav is National Convener of the Bharat Jodo Abhiyan. He tweets @_YogendraYadav. Rahul Shastri is a researcher. Shreyas Sardesai is a survey researcher associated with the Bharat Jodo Abhiyan. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

Yogendra Yadav’s pathological hatred for anything remotely BJP or RSS is an open secret if one removes ones’ ideological blinkers. Expecting any fair analysis from him will be a futile exercise.