Politicians and political strategists everywhere in the world now use Bill Clinton’s pithy phrase, “It’s the economy, stupid”, to describe a truism they have known all along: people vote based on how they feel about their prospects in life. An ability to get—or move up to—a new job is what most people measure that by. Which is why, world over, politicians campaign heavily on job creation. Even though they often have very little direct control over it.

As a rule of thumb, a population that has seen its job market thrive re-elects incumbents; one that has experienced stagnation or low growth in jobs throws them out. In the run up to the Lok Sabha elections, therefore, it’s useful to take stock of what the last few years have been in terms of job creation in this country.

To start with, let’s ask some basic questions. How many new jobs have been created in, say, the last year? Or, in the last few years? And of those jobs, what is the sectoral break-up? Ideally, one wants a lot of jobs to be created in the manufacturing sector. Both politicians and economists agree that this is a sustainable way to lift people out of unproductive low-wage work such as agricultural labour. Additionally, we want more people to get regular jobs in the formal sector as opposed to the informal sector.

Let’s evaluate India’s performance on these questions.

Also Read: India Employment Report paints a dire picture for youth. But it has praised Modi govt too

Workforce boost to the ‘wrong’ sector

About 9.9 million new jobs were created in 2022 compared to the previous year, according to the International Labour Organization’s India Employment Report 2024, based on data from India’s Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS).

This figure encompasses all jobs created in the country across all sectors for all citizens of working age. For context, India produces about 10-12 million college graduates each year. And about four times as many people who never attended college become of working age as well. So, the total jobs created is somewhere between a third and a fourth of the total number of people who became eligible to work that year, depending on how one counts. The queue also includes vast numbers of unemployed people from previous years.

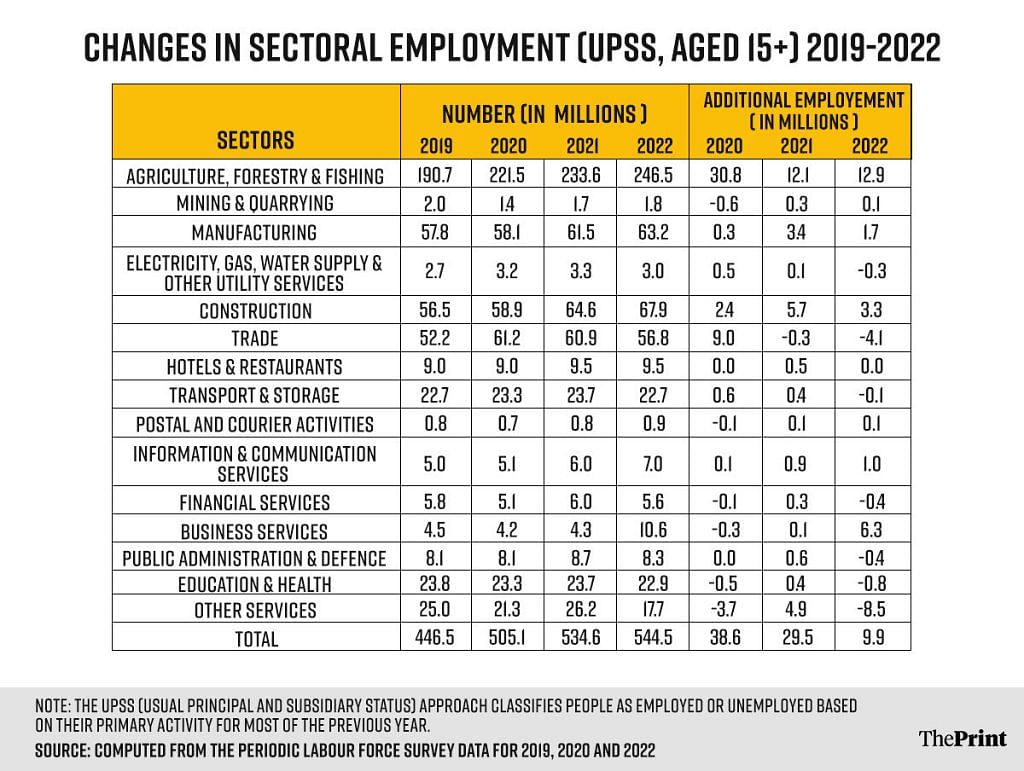

Now, according to the same ILO report, the number of workers in agriculture and allied sectors increased by 12.9 million in 2022—more than the net addition of 9.9 new million jobs. This suggests losses in other sectors. This is the exact opposite of what we want as a society that seeks to move people from an agrarian economy to a manufacturing one. India added a mere 1.7 million jobs in manufacturing in 2022, which is less than 10 per cent of the jobs added in agriculture! Instead of moving away from an agrarian economy to an industrial one, it seems the country is moving backwards by becoming even more agrarian.

Impact on productivity

Agriculture is, as I’ve previously written, disguised unemployment. Additional employment in this sector, for the most part, shows a lack of job opportunities in other sectors. But what is even more troubling is that younger people are taking up jobs in agriculture on a massive scale. Typically, younger workers, as a cohort, are more educated. These workers tend to take up jobs in newer sectors of industry while older workers continue with agriculture. Except, in recent years, more than half of all jobs that young people have been taking up are in agriculture! Worse, this figure—of young people taking up jobs in agriculture—went from around 37 per cent in 2019 to 52 per cent in 2022. Therefore, not only are young people still taking up these unproductive jobs, but the rate at which they are doing so is accelerating!

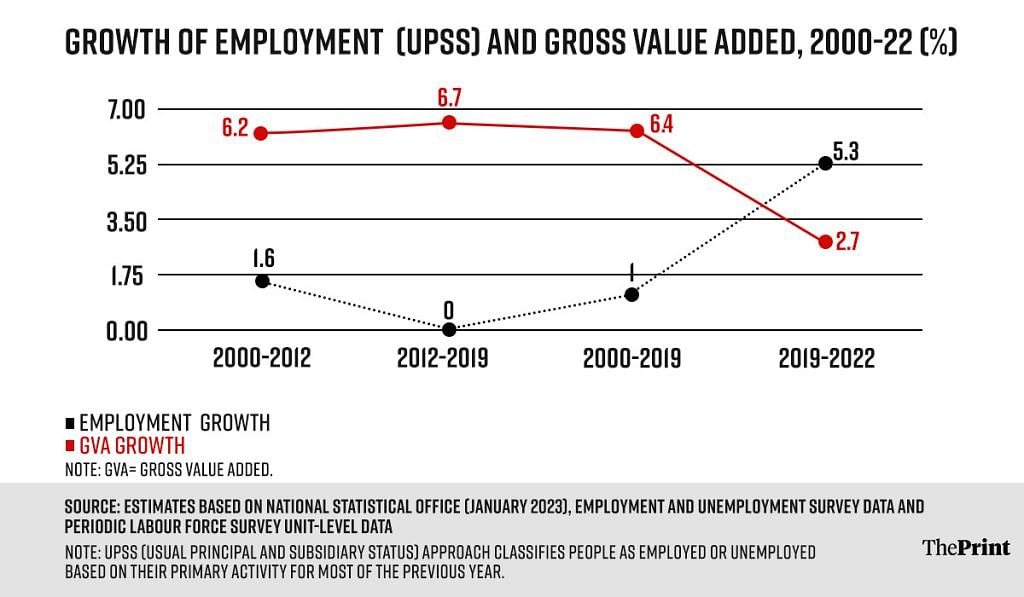

This shows up as falling productivity in the data. Even when there was growth in jobs created, the total value added did not keep pace. This points to the creation of low-quality jobs, amounting essentially to disguised unemployment.

The stagnation in job creation, as well as the decline in job quality, are not recent phenomena. This trend, in fact, has been unfolding since the turn of the century. For example, between 2012-2019, years that include both the first term of the Modi administration and the previous government’s tenure, the total jobs in the country remained a relative constant. In 2012, the total estimated number of jobs stood at 466.3 million. In 2019, it was 466.5 million. In these seven years, it’s likely that 100-150 million young people became of working age while hardly any additional jobs were created.

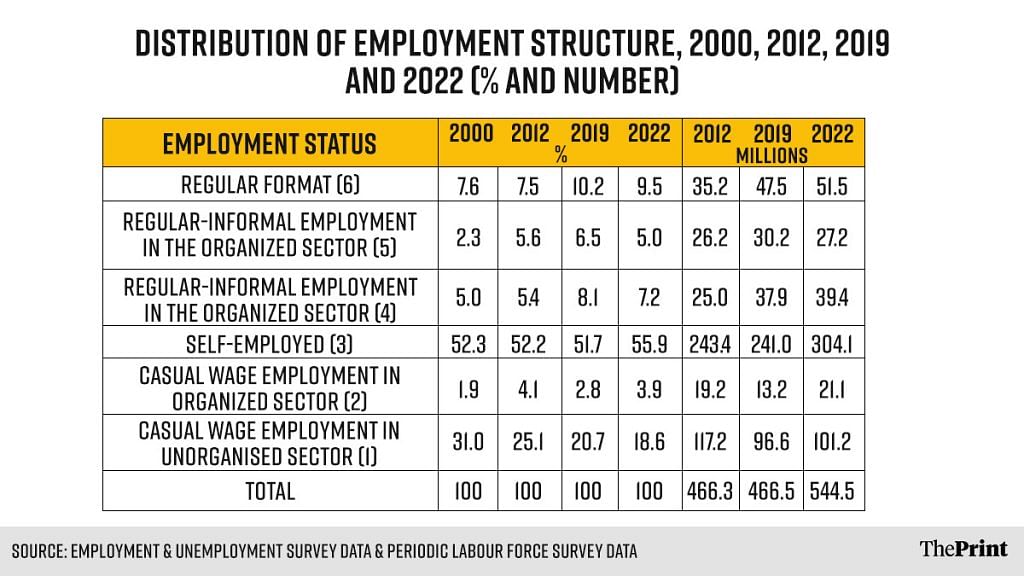

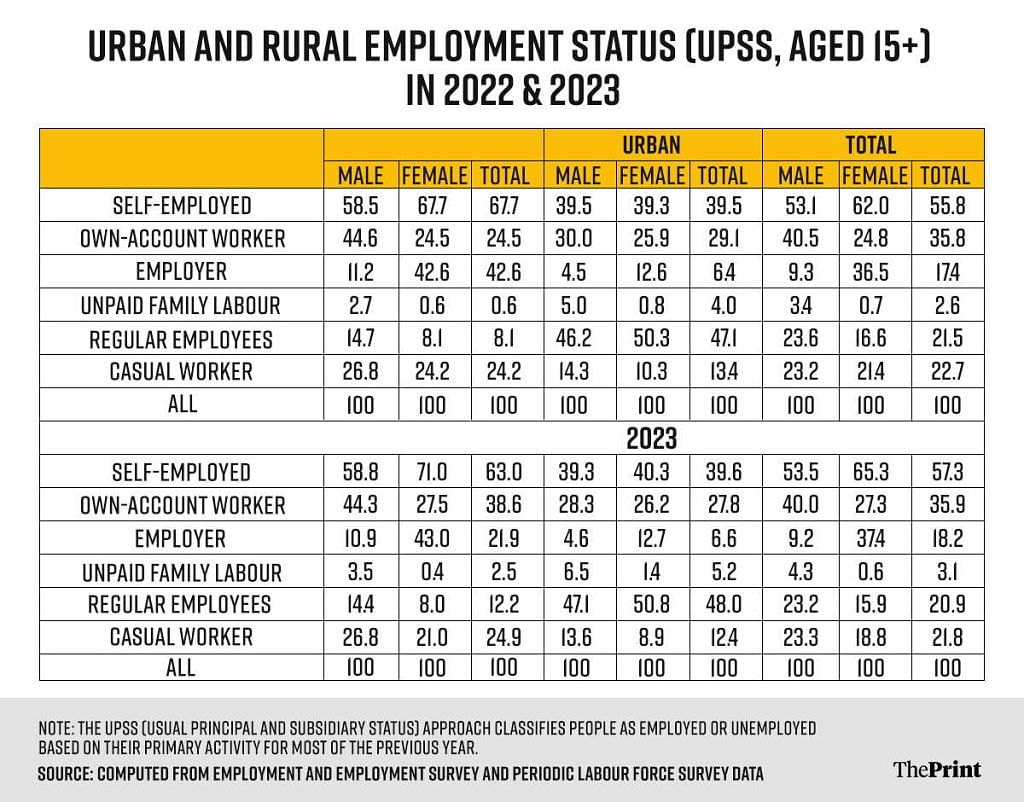

Another important yardstick of job creation is whether these are regular jobs in the formal sector. When one mentions the word “job”, the image that typically comes to mind is that of an office or factory worker with a salary. But that type of work accounts for less than a tenth of all jobs.

Between 2022 and 2023, this category of jobs—classified as “regular” by the PLFS—actually dropped as a ratio of overall jobs. The only category of jobs that showed growth were “self-employed” and “unpaid family labour”. These are both, again, forms of disguised unemployment, and their growth in the relative mix is only a cause for concern.

Also Read: India’s youth need jobs not freebies. Can govt deliver before demographic dividend fades?

Big promises don’t cut it

A shocking 71 per cent of India’s youth fall into the NEET category—that is, not in employment, education, or training. It’s no wonder, then, that some of these young people take extreme measures just to find a job, like going to Nicaragua and then taking an arduous and life-threatening trek north to the United States. Others have jumped into the well of Parliament, breaching security and risking serious consequences.

A large unemployed youth population, especially young men, has been a predictor of revolutions world over. This has been true from the French Revolution to the Arab Spring. Politicians are not unaware of the risk that unemployed youth pose both to their political careers and to general peace. Which is why, Narendra Modi, for instance, promised to create 2 crore jobs per year. That promise hasn’t materialised, though.

The data is grim however one slices it. What was touted as a demographic dividend for India a couple of decades ago has turned sour. Our best hope now is to avoid the ill-effects of having a large unemployed youth population, as opposed to reaping the rewards of their potential productivity.

Politicians and political parties, as Narendra Modi and BJP found out, do not have a magic wand. Everyone wants to see massive job growth. But the reality is that job growth is a downstream effect of good economic policymaking. Jobs can’t be willed into reality despite bad decision-making on the policy front. For people to move up the value chain and hold productive non-farm jobs, they need to first get an education, be healthy, and feel secure. That human capital needs to be built, as a necessary condition. The data on state-level discrepancies shows exactly that, as well. States with higher levels of education and human capital formation have better employment opportunities for their citizens, and at higher wages.

When a politician seeks your vote, perhaps the most important question to ask is: what is their long-term strategy to build up human capital? And how do they aim to transform that capital, once formed, into a productive labour force? If their answer boils down just to being “business friendly”, you know they haven’t thought it through. If their answer is, “Well, that is complicated and there are no easy answers”, maybe that person knows what the job is.

Knowing the job is the first step to doing it.

Nilakantan RS is a data scientist and the author of South vs North: India’s Great Divide. He tweets @puram_politics. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)