Why did Draupadi, after suffering abuse at the hand of the Kauravas, and Chanakya, after being insulted by the Nanda king, keep their hair loose until the Kauravas were avenged and the Nandas were vanquished with Chandragupta installed as king? Why do Buddhist, Jain, and Brahmanical renouncers shave their heads, while Sikh men and Brahmanical forest hermits keep their hair long and uncut—the former tying it in a turban and the latter leaving it unkempt and matted? These questions require us to untangle the complex grammar of hair manipulation in India, and, more broadly, in various ancient cultures. The ways in which societies manage hair, the social expectations for its treatment at different times and stages of life, provide a unique lens through which to examine cultural practices.

Throughout history, humans have had a neurotic obsession with hair, especially head hair. We cut, shave, style, or even neglect it. Recently, I came across the staggering headline: “Hair Care Market to Soar Past 122 Billion US Dollars by 2030.” The annual global spending on hair products exceeds the GDP of over 100 countries, including Sri Lanka and Nepal. We expend a lot of time, care, and money on our hair. And it appears to have been so for much of recorded history. When humans want to say something important, they often do so with their hair.

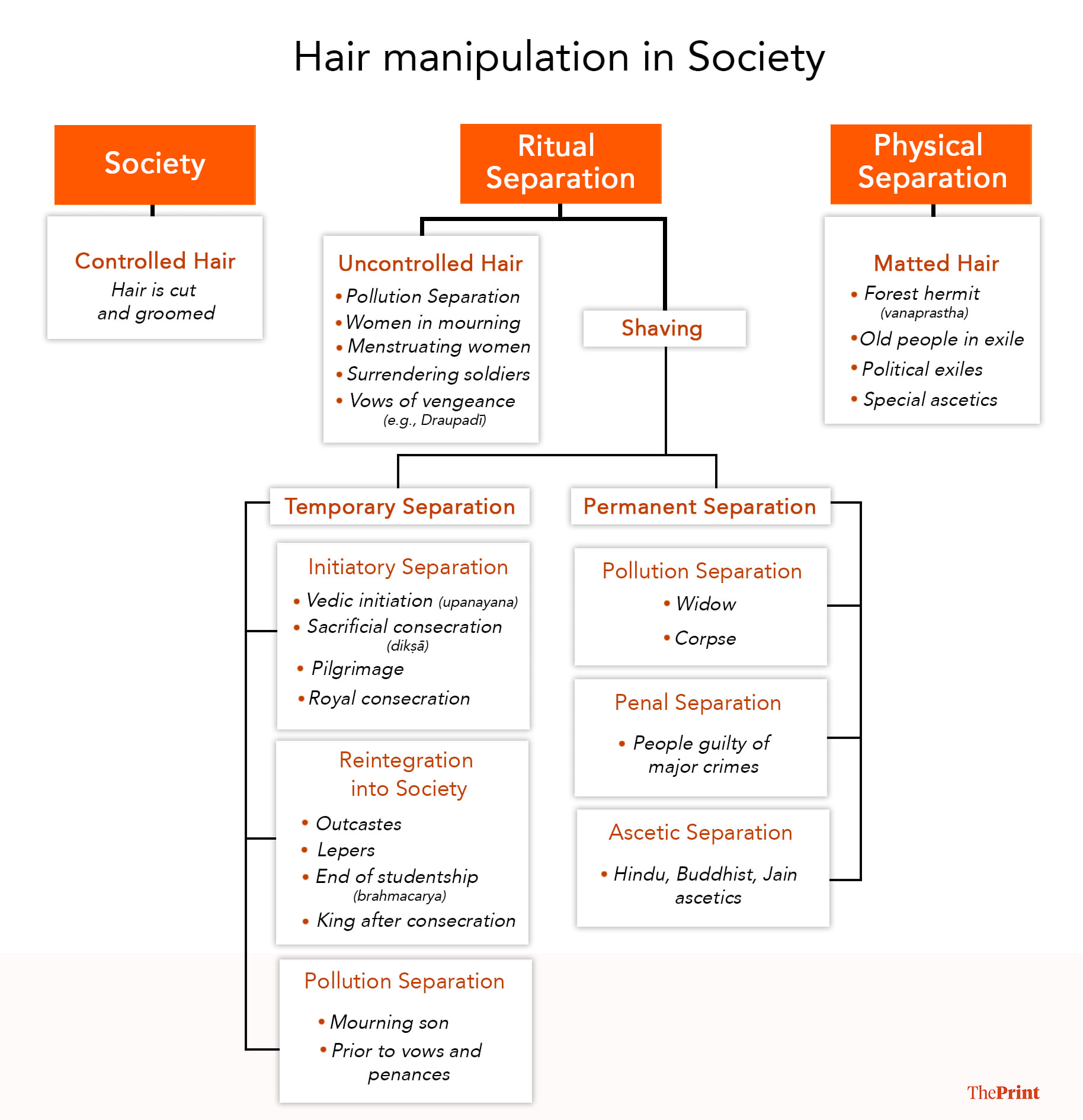

In pre-modern India symbolic manipulations of hair appear as variations of three central themes: (1) groomed control of hair, (2) the ritual shaving of hair on the head (in case of adult males, this may also involve shaving the beard), and (3) the neglect of hair, resulting in either loose and unkempt or dirty and matted, often accompanied by the neglect of nails, and, in the case of males, of the beard. Each of these forms of hair manipulation carried deeply social, widely understood meanings, placing the individual with the manipulated hair in different relationships to people within society. [See chart]

Central themes of hair manipulation

Groomed and controlled hair is the hallmark of publicly recognised societal roles, especially for adult men and women (see Hallpike). Such controlled social hair is the point of reference for other hair manipulations from which they derive their significance. For instance, married men typically kept their hair short, while women wore their hair long, oiled, and restrained in knots or braids.

The groomed control of hair is especially demanded when appearing in public, where loose and uncontrolled hair carries a variety of socially recognised meanings and messages. Loose hair, especially for women, is a sign of domestic informality or sexual intimacy. In sculpture, for example, erotic couples are often depicted with flowing hair. Mendicants are warned not to seek alms from a muktakeśinī (“a woman with loose hair”), which could indicate either recent sexual intimacy or menstruation. In the warrior ethic, a soldier is warned against killing an opponent who has let down his hair (muktakeśa), a sign of surrender.

The most common temporary social separation occurs during initiation ceremonies. Initiation rites worldwide are commonly recognised as having three moments: separation, liminality, and reintegration. The initiate is first ritually separated from society as well as from his or her social rank and role, and left in an ill-defined marginal state. The initiatory rite concludes with the reintegration of the initiate into his or her new status within society. In South Asian traditions, most initiatory separations are accompanied and signalled by the ritual shaving of the initiate. For example, when a young boy undergoes Vedic initiation (upanayana), a man is consecrated (dīkṣā) prior to his performing a Vedic sacrifice, and a king is anointed (abhiṣeka)—all of them are first shaved before these initiatory rites. Indeed, these ceremonies are presented expressly as the new birth of the individual with many explicit statements and symbolic enactments signifying the initiate’s return to the womb to become an embryo or an infant—the asexual and hairless condition.

Social intercourse is forbidden with people tainted with ritual pollution. These people are ritually separated during their period of impurity. Some of these temporary periods of separation, such as those created by the death of a close relative, can also be marked by shaving. A son, for example, is expected to shave his head at the death of his father or mother. A more permanent ritual separation from society occurs in the case of a widow. The social position of a widow has undergone repeated changes in Indian history. There is at least one period when the ritually impure, inauspicious, and unmarriageable state of a widow was signalled by the shaving of her head. The permanence of this condition, moreover, required that she keep her head permanently shaven, and in this and other customs, a widow often resembled an ascetic.

The best-known ritual shaving associated with a permanent separation from society is, of course, that of a world-renouncing ascetic—Hindu saṃnyāsins, Buddhist and Jain monks, and their female counterparts. A central feature of the rites of initiation into the ascetic life in all these traditions is the removal of head and facial hair. Throughout their life, these ascetics keep their heads and faces clean-shaven. Ascetics, as well as all people ritually shaven, are forbidden to engage in sex. For most, this is a temporary condition required by a rite of passage or necessitated by ritual pollution. For the ascetic, on the other hand, it is permanent, and therein lies the difference between ascetic and other forms of ritual shaving. For the ascetic, shaving indicates his or her removal from socially sanctioned sexual structures, and, a fortiori, also from other types of social structures and roles.

Also read: Billie razor’s ‘real body hair’ ad is insidious, harmful and exploitative

Matted hair, withdrawal from society

Finally, we have a unique manipulation of hair by refusing to manipulate it at all—that is, the utter neglect of hair, allowing it to grow matted and unkempt. In Indian history, we can identify at least three distinct types of matted-haired people who have withdrawn or have been forced to withdraw physically from society. First, there are the forest hermits called Vaikhanasa or Vanaprastha, and second, the aged. Old people, especially old kings, within the Hindu institution of the four orders of life (ashramas) were expected to leave their family and society and assume a forest mode of life. These two classes—the hermits and the retirees—are often collapsed into a single category in Indian legal literature.

The third class consists of political exiles. The epic heroes of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, the five Pandava brothers and Rama, for example, are all sent into political exile. Significantly, political exiles assume the bodily symbols and the mode of life of forest hermits. To understand the symbolism of matted hair, it is necessary to locate it within the larger grammar of the symbols associated with physical withdrawal from society in ancient India. Besides long and matted hair, bodily symbols of forest living included keeping a long and uncut beard, long and uncut nails, eating only uncultivated forest produce, wearing clothes made from tree bark or animal skin, and frequently leaving the body unclean. One can decipher from this symbolic grammar the following statement: a matted-haired individual withdraws from all culturally mediated products, institutions and geographical areas, and returns to the state of nature, to the condition of the wild.

A particular type of hair manipulation may become a ‘condensed symbol,’—a symbol so powerful that it encapsulates all the diverse aspects of the symbolised. Condensed symbols include a national flag or anthem. Hair thus remains both a means of strong institutional control and an instrument of liberation from and critique of social and institutional controls.

Patrick Olivelle is Professor Emeritus of Asian Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. He is known for his work on early Indian religions, law, and statecraft. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)