Two weeks ahead of the Union Budget, India’s most reassuring macroeconomic indicator, low inflation, is also the most misleading. While price pressures appear under control and the prevailing narrative suggests stability, this apparent calm disguises a deeper fragility. The economy is not experiencing overheating that requires gentle cooling; rather, it is grappling with the challenge of generating broad-based demand, and price stability has been achieved not through income recovery, but through restraint.

That distinction matters a great deal because the Budget will be constructed based on policymakers’ perceptions of their accomplishments. If low inflation is interpreted as a success, fiscal ambitions will be limited. Conversely, if it is perceived as indicative of weak demand, the policy response will have to be suitably adjusted. The divergence between these two interpretations will influence India’s growth trajectory well beyond the Budget cycle.

When inflation falls but incomes do not rise

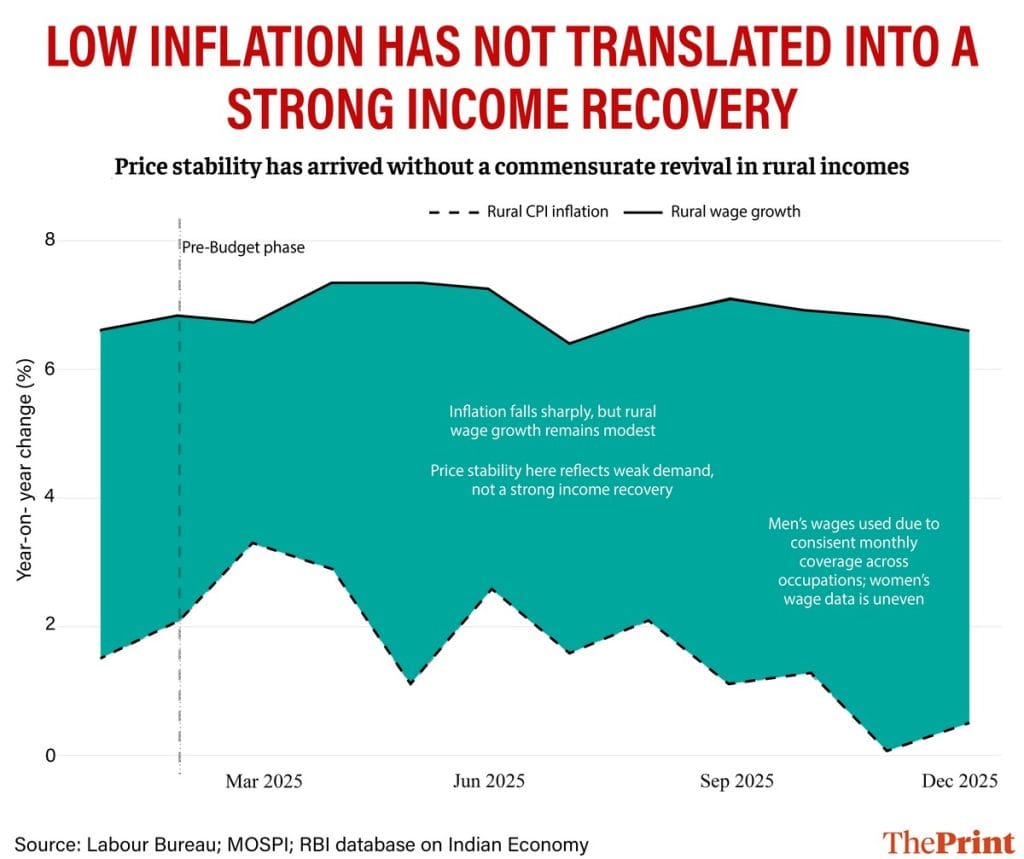

The chart below presents a subtle yet compelling narrative: throughout the year, rural Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation has significantly decreased, while rural wage growth has remained modest and inconsistent. The trajectories of these two indicators do not converge; rather, they drift apart. This price stability does not signify increased productivity or enhanced purchasing power; instead, it reflects a cautious economic environment.

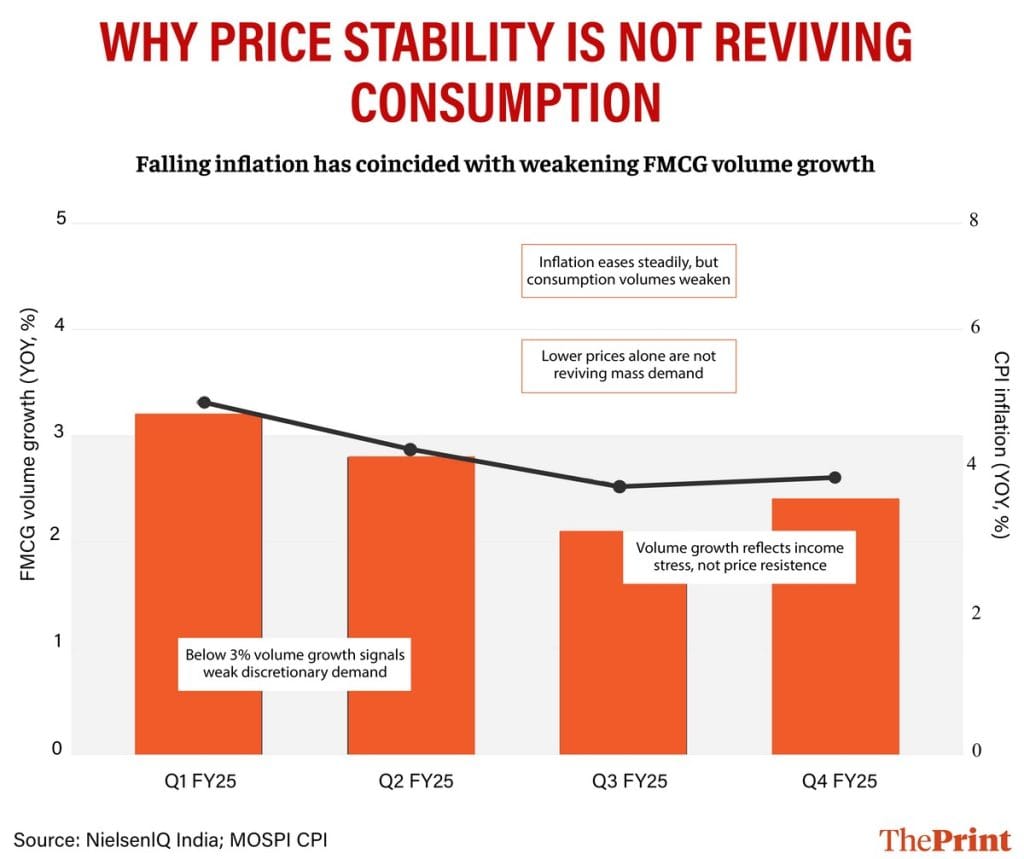

This divergence matters because rural incomes are foundational to India’s mass consumption economy. When wage growth remains stuck in the mid-single digits, even as inflation declines below this level, households do not perceive an increase in wealth. Instead, they feel constrained, leading them to rebuild financial buffers, reduce discretionary spending, and delay consumption decisions. That behaviour is evident across various data points— for instance, the FMCG volume growth slowed from about 3.2 per cent in Q1 FY25 to close to 2 per cent by Q3 FY25, before only a modest recovery, even as inflation continued to ease.

This situation does not represent a failure of monetary policy; inflation control has been effective. However, it has been effective in an economy where demand is already weak. In such a context, disinflation does not unlock spending; rather, it reinforces cautious behaviour. The policy error would be to assume that price stability inherently restores confidence, which it does not when incomes are fragile.

This is why the context of the Budget is crucial. An economy that appears stable in terms of inflation but stressed in terms of incomes prior to the Budget is not prepared for fiscal consolidation. Such an economy risks confusing restraint with resilience.

Why price stability is not reviving consumption

India’s consumption slowdown is not primarily a consequence of price fluctuations but rather an issue of income. When volume growth falls below three percent, discretionary demand comes under pressure, even as inflation declines. This situation is not indicative of price resistance but rather a deterioration in purchasing power.

This distinction is crucial for effective policy formulation. If weakness in consumption were driven by inflation alone, price control measures would suffice. However, the concurrent weakening of volumes and declining inflation suggests a lack of household confidence in future income. In such circumstances, further price suppression does not stimulate demand; instead, it compresses profit margins and delays recovery.

The Budget risks misinterpreting this situation. While benign inflation may create the illusion of limited fiscal space, the underlying consumption stress is more structural than it appears. The data indicates that without income support or productivity-linked wage growth, demand will not recover autonomously.

This is the point at which trade enters the picture.

How trade becomes India’s silent stabiliser

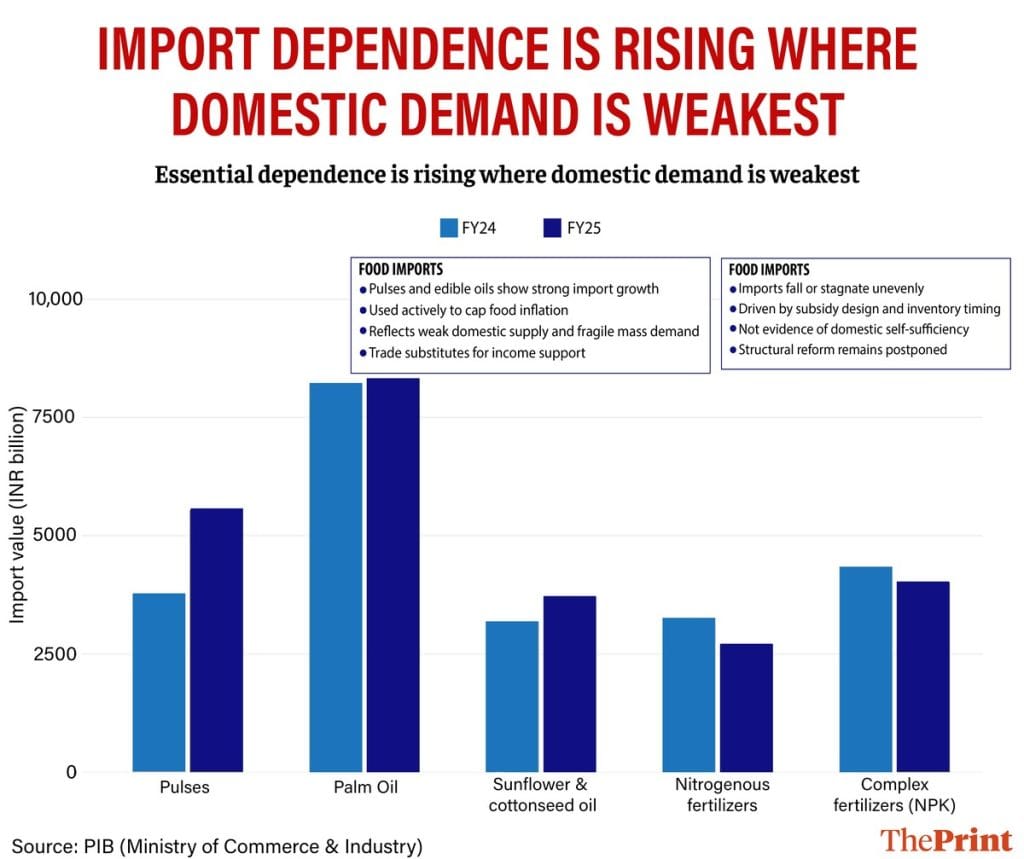

India has relied on food and fertiliser imports as part of its strategy to address this imbalance, as seen in the chart below.

There has been a significant increase in the imports of pulses and edible oils, despite weak domestic demand. These commodities are not luxury items driven by a consumption surge; rather, they are essential goods. The expansion of their imports is a deliberate policy decision.

India possesses a distinctive ability to stabilise prices through trade mechanisms. Import duties can be swiftly adjusted, and there is an abundance of global suppliers for essential commodities. In response to potential food inflation, import restrictions are eased, while export bans are implemented when domestic prices escalate. Fertiliser imports increase when subsidy structures render domestic production less attractive.

This approach should not be misconstrued as incompetence; it is a stabilisation strategy. However, it does entail a trade-off. Utilising imports to cap prices can substitute for more challenging reforms, such as income support, wage growth, productivity enhancement, and market deepening. Trade becomes a shortcut to price control rather than a tool for enhancing competitiveness.

The data on fertilisers underscores this point. Fluctuations in imports reflect the timing of subsidies and price management rather than self-sufficiency. The system is optimised to maintain price stability rather than to address structural deficiencies. In both food and inputs, trade absorbs pressures that should have been mitigated by domestic demand and supply reforms.

This strategy is effective in the short-term, as prices remain low and inflation appears controlled. However, demand does not recover, households remain cautious and growth becomes uneven and reliant on external factors.

Also Read: India’s NPAs are at record low. Why it can be the most dangerous phase

The Budget choices India must make

Collectively, the three charts convey a unified narrative. India has attained price stability without a corresponding recovery in income. Consumption has weakened even as inflation has subsided. Trade has been employed to manage the consequences rather than address the underlying causes.

This creates a precarious illusion ahead of the Budget. Inflation appears benign, while fiscal space seems constrained, reducing the perceived urgency for demand revival. Beneath the surface, however, households remain vulnerable, and growth remains lopsided.

The prospective risk is evident. An economy that depends on price suppression rather than income expansion will encounter challenges in generating sustainable growth. External shocks will propagate more rapidly, trade dependence will intensify, and policy will remain reactive.

Nonetheless, the opportunity is equally apparent. If this Budget acknowledges that low inflation is not a triumph but a cautionary signal, it can pivot. Toward income-linked expenditure, rural productivity, wage-supportive infrastructure and reforms that enhance purchasing power rather than merely suppress prices. India need not abandon inflation discipline; it needs to stop mistaking it for demand recovery.

The government should prioritise measures that directly strengthen household purchasing power and that would imply protecting real rural wages, front-loading employment support, easing working-capital stress for small firms, and ensuring that public capital expenditure translates into actual job creation instead of merely asset formation. Trade policy can continue to stabilise prices, but it cannot substitute for income growth.

The true test of this Budget will not be subsequent stability of prices, but whether households regain the confidence to spend.

Bidisha Bhattacharya is an Associate Fellow, Chintan Research Foundation. She tweets @Bidishabh. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)