With Tarique Rahman taking the oath as prime minister, Bangladesh has finally transitioned to an elected government. This marks the end of nearly 1.5 years under the interim administration led by Muhammad Yunus—and signals a new chapter in the country’s foreign policy, especially in resetting ties with India.

Yunus made it his personal mission to distance Bangladesh from India, filling Dhaka’s diplomatic corridors with anti-India narratives.

Even in his farewell speech on 17 February, while suggesting economic integration with Nepal and Bhutan, he referred to ‘seven-sisters states’ without mentioning India. It reflected his torn legacy of jeopardising ties with New Delhi. He wants the new administration to ensure that Bangladesh is “no longer submissive” and is not guided by the directives of other nations—which is obviously a sly dig at India.

While the new Rahman-led government will certainly bring some changes, what is needed, however, is a complete de-Yunusification of the administration, one that restores New Delhi’s stature as a valued neighbour and historical partner. The ruling Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) acknowledges India’s role in Bangladesh’s independence. De-Yunusification would not only be a major step toward normalising the bilateral relationship, but also restore the trade and business partnerships that the two countries have enjoyed over the past seven decades.

The early signs

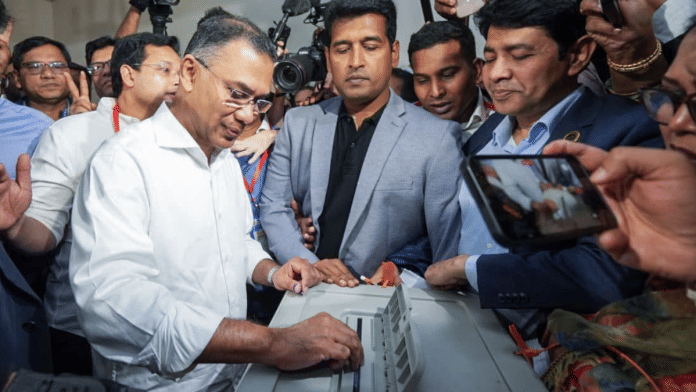

Since the announcement of the election results on 13 February, the BNP seems to be taking steps to improve ties with India. First, it invited Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Dhaka for Rahman’s oath-taking ceremony. Since Modi couldn’t travel because of the AI Impact Summit in New Delhi and a scheduled meeting with French President Emmanuel Macron, Lok Sabha Chairman Om Birla went there instead, accompanied by Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri. Going by the diplomatic overtures, the invitation matters.

Second, BNP Secretary General Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir said that ties with India will not be held ‘captive’ to New Delhi’s decision to shelter deposed Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina since August 2024. While Hasina’s in absentia trial and death sentence resonate with the BNP leadership, Yunus’ ‘all-or-nothing’ demand for her return may not hold ground. After all, India is more than just a neighbour.

Third, the termination of Faisal Mahmud, the Minister (Press) of the Bangladesh High Commission in New Delhi, is in line with the new administration’s intention to address the ‘diplomatic biases’ — something that the Yunus administration had kept handy and deployed everywhere. During Faisal’s tenure, Chief Adviser Yunus’s official X handle repeatedly targeted Indian media organisations and columnists, often picking op-eds, writing rejoinders, or accusing outlets of spreading propaganda.

Fourth, the BNP’s continued engagement with India, even during the peak election hours—something that could have constituted an election risk given the strong anti-Hasina movement. Any visible outreach to New Delhi could have triggered backlash, undermined the BNP’s anti-incumbency positioning, and complicated its domestic political messaging. But the BNP seemed more comfortable with its outreach, electoral appeal, and winning volume, so it left such matters to the ‘protest party’—the National Citizens Party— which won six seats.

Furthermore, Rahman’s 35-minute meeting with Foreign Minister S Jaishankar in December seems to have broken the ice, and both Delhi and Dhaka will seek to rebuild the ties on those threads.

Also read: Toppling govts is easier than winning polls for protesters. Bangladesh is the latest proof

The way forward

The damage caused to the India-Bangladesh relationship by Yunus’s 1.5 years in office is prominent and would require more than just diplomatic overtures. Rahman would need to double the effort, considering there are dozens of pending issues, including the renewal of the Ganga Water Treaty, border security, illegal migration, visas, and medical tourism.

The new government must also ensure that Bangladesh is not used against India’s security interests, which would require tempering down the euphoria around the so-called China-led trilateral projection—China-Bangladesh-Pakistan—and a rapprochement with Pakistan.

Lastly, as Rahman begins the de-Yunusification drive, New Delhi will also have to ensure that none of its actions is deemed ‘hegemonic’ and ‘big brotherly’. It must resume with a subtle and proactive ‘neighbourhood first’ approach.

History shows that any downturn in ties with Bangladesh results in extremists and expansionist actors taking control of regional peace. Therefore, the restart must be delicate, futuristic, more realistic—where interests are involved—and less hostile.

Rishi Gupta is a commentator on global affairs. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)