In many democracies, elected politicians spend a substantial amount of time in the legislature to propose, debate, and vote on policies. In developing countries, politicians face an extra duty – they are also expected to spend a large part of their time with constituents listening to their concerns, solving conflicts, and helping them navigate the local bureaucracy. As India votes, it is timely to ask – how much time do Indian politicians spend in legislative assemblies and why has this changed over time?

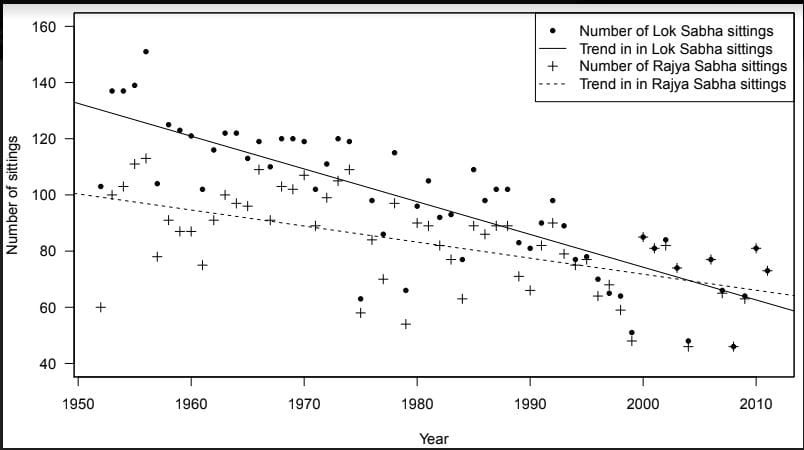

Figure 1 shows a decline in parliamentary activity, measured as the annual number of sittings in the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha. In order to better understand what might explain this decline in legislative activity, we studied the performance of Vidhan Sabhas, India’s state legislative assemblies, in 15 Indian states from 1967 to 2007. Our dataset of 140 assemblies allowed us to compare legislatures in different states as well as to examine trends across the states over time. This analysis revealed two clear patterns: first, there is considerable variation in the activity of state assemblies across states; and second, despite this variation, there has been an overall decline in legislative activity in Indian state assemblies over time.

Also read: This data shows why Indian MPs don’t truly represent their people

One explanation may be the fragmentation of the legislative assemblies themselves. In much of the political-science literature, the expectation is that career-oriented politicians seeking re-election will try to make their mark by passing legislation that is important to their constituents. From this perspective, greater political fragmentation and competition should contribute to more debate and dialogue as well as the enhancement of legislative professionalism as the legislative body becomes a vehicle for political opportunism.

In India, however, the opposite seems to hold true. We find that the legislative assemblies dominated by a single party have tended to have far more legislative debate than the more fragmented assemblies. Politics in Indian states has grown more competitive and fragmented in recent decades as the dominance of the Indian National Congress (INC) party has gradually waned. In states with dominant parties and low political competition, legislative activity is fairly high. Facing a weakly competitive environment, both in the assembly and in the constituencies, legislators seem willing to invest time activity. This was the case when the INC dominated Indian politics. With legislative state assemblies becoming more fragmented, much of the debate seems to have moved out of the assemblies, and legislative meetings have become fewer and shorter.

Also read: Why voters don’t turn up in larger numbers in Lok Sabha elections – all politics is local

Another explanation lies in the pressures Indian politicians face to engage with constituents. Politicians in India are expected to help their voters in practical matters by negotiating with the local administrative bureaucracy, attending local social functions, and networking with influential people. Many observers argue that for re-election, these activities are more important to politicians than their actions in the legislature. From our findings show that when politicians have to cater to a large electorate at home, they may prioritise spending time in their constituency rather than in meetings in the assembly, which could be associated with less legislative activity. This suggests that the size of the units of political representation can help explain the variation in legislative activity in the Indian legislatures.

Our findings indicate that legislative institutions suffer when candidates and parties find themselves torn between legislative service and constituency demands. While some have argued that this is the result of a general deterioration in political culture, we propose that the explanation may lie in the growth in political fragmentation and increasing pressures on politicians in their home constituencies. Further exploring how candidates and parties choose to prioritise different types of activities presents a promising agenda for future research.

This is a summary of a research article Fragmentation and Decline in India’s State Assemblies: A Review, 1967–2007.

Francesca R. Jensenius is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Oslo. Pavithra Suryanarayan is an Assistant Professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS).