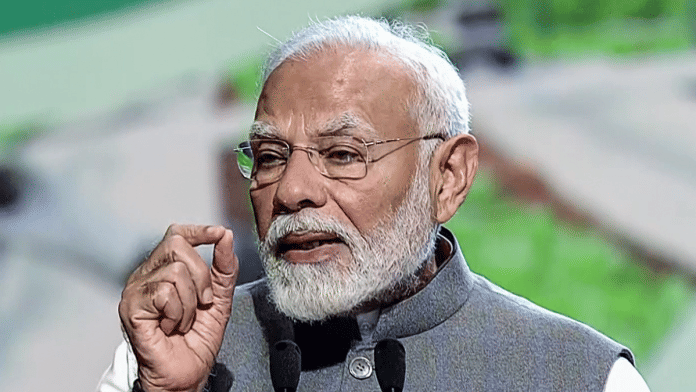

The Narendra Modi government’s relationship with India’s private sector resembles a bad marriage — complete with a euphoric honeymoon phase, subsequent mutual disappointment, bargaining and compromise, accusations of cheating, recent public criticism, and a seeming breakdown of communication.

Divorce, of course, is not an option. So, the question is, how will the two seek to save the relationship? Or will it continue in this state of marital discord, to the detriment of India?

The marriage began when Modi came to power in 2014. In the run-up to the 2014 general election, the private sector was behaving like an ecstatic bride or groom-to-be. Modi, the prospective spouse, could do no wrong and was seen as the one to provide the private sector a good and prosperous life in India.

The sector’s previous relationship, with the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA), had ended on a sour note, after all. The UPA’s focus on welfare measures — rather than pro-business reforms — and the perception of corruption had begun to irk India Inc.

Buoyant honeymoon, with some dark clouds

The post-2014 honeymoon period with the Modi government lived up to its name. According to CMIE data, a total of 1,383 new private sector projects were announced in 2014-15, about 20 per cent higher than in the previous year. This number kept rising over the subsequent couple of years to touch 2,351 announcements in 2017-18. New relationships are full of loving promises.

But, as anybody in a healthy relationship will tell you, promises only go so far — they need to be backed up with action. Despite the seemingly ebullient investment atmosphere, reality painted a less sanguine picture.

Private sector gross capital formation as a percentage of GDP, a metric of the sector’s actual investments, stood at 24.2 per cent in 2013-14, a year before the relationship started. One year in, in 2014-15, it slid to 23.1 per cent, and fell further to 21.9 per cent by 2019-20.

The private sector was clearly not committing to the relationship.

Bargaining, wooing, trying to rekindle the love

The somewhat jilted government then took a radical step to get things back on track. Somebody has to make the first move, right?

In 2019, it cut corporate tax rates drastically from around 30 per cent to 22-25 per cent, and even to 15 per cent for new manufacturing firms. If the private sector wanted a more conducive and comfortable home environment, then the government was there to provide.

But, soon after, tragedy struck. Both sides of the relationship were dealt a body blow by the Covid-19 pandemic. While the government had its hands full trying to take care of the kids — the Indian public and small and medium enterprises — the corporate sector was focused on ensuring business continuity and profitability.

The pandemic brought with it a pause in the government-corporate sector relationship troubles. Each side gave the other time to recover.

The private sector used this time to pare down its debt levels and repay large chunks of the more costly loans it had taken. Corporate debt, not counting the financial sector, fell nearly two per cent to Rs 43.2 lakh crore by March 2021 from where it was the previous year.

The government, of course, bore more of the pandemic burden, with its fiscal deficit shooting up to about 9.2 per cent of GDP in 2020-21. But it was able to quickly bring this down steadily over the next few years, to 5.6 per cent by 2023-24. During this time, attention could again come back to adding a spark to the marriage.

In 2020, the government had announced about 13 production-linked incentive schemes to encourage the private sector to invest in the economy. While some of these, such as the ones for electronics manufacturing, have taken off, the remaining ones haven’t seen adequate levels of activity.

Simultaneously, the government also began to significantly increase its own investments in the economy through a huge capital expenditure push every year, in an attempt to encourage the private sector to take a cue and do the same.

Yet, while the government was once again trying to build a nice home, the private sector still didn’t seem too enthused.

Also read: Census, privatisation absent from Budget 2024. It’s a calculated political move

Growing frustration, public attacks, private cribbing

Even though private sector gross capital formation as a share of GDP began to again grow post-pandemic after years of near-consistent decline, the government still doesn’t seem happy.

The problem, it says, as explained in the Economic Survey presented to Parliament, is that the private sector wasn’t investing in areas that created growth, such as new machinery and equipment. It’s like if your partner showed they were spending money, but that it was largely going toward beer and gaming PCs rather than things that could actually increase your household’s income.

As it often happens when frustration with your partner grows, you tend to lash out. Public criticism and sensational accusations, such as of cheating, soon followed. Remember Modi’s pre-election accusation that tempos of black money from Adani and Ambani were going to the Congress?

Or, how the Economic Survey said that the private sector’s contribution to the “toxic mix” of India’s social media and fast-food addicted habits was “substantial and myopic”.

Another indication of an unhappy relationship is passive-aggressive communication by both sides, even when they are speaking to each other. On the one hand, Modi spoke to business leaders at the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) post-budget conference last month in glowing terms, painting a rosy picture of the opportunity that lay before them in India.

On the other hand, a few hours later and at the same conference, commerce minister Piyush Goyal lambasted the assembled corporate leaders for being too self-centred. He even evocatively lamented: “Taali do haath se bajti hai (It takes two to tango).” That’s a plaintive lamentation from a frustrated partner, if there ever was one.

Finance secretary TV Somanathan, meanwhile, pointed out that the private sector was the one not communicating well enough. In a post-Budget interview with ThePrint, he spoke about how industry leaders either only ask for incentives and tax cuts or only tell the government what it wants to hear.

Talk about a communication breakdown.

The thing is, a large part of Somanathan’s criticism rings true. Look back over the last 10 years and try to find any corporate leader who has publicly voiced any sort of criticism of the government. You’ll find next to none. Yet, if you speak to these leaders privately, all they do is crib about tax officials, onerous business compliances, and low to mid-level corruption.

The government and corporate India need marriage therapy and honest talk. India’s corporate sector needs to toughen up and be brave with its criticism. The government, for its part, needs to listen and not lash out. A big reason for corporate India’s silence is fear.

Open communication is key, and the winner will be their marriage — in this case, represented by the Indian economy.

TCA Sharad Raghavan is Deputy Editor – Economy at ThePrint. He tweets @SharadRaghavan. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)

It is wrong to say that Modi govt. was married to private sector since 2014. Modi govt was married to only a select group of business houses, not to the private sector as a whole. This is a corrupt relationship. The private sector as a whole always stayed hopeful that Modi govt will listen to them as a whole, but that never happened and it seems will never happen in Modi’s tenure. Because Modi the illicit relationship Modi has with the two business houses is much stronger. So what the author hopes is unattainable by Modi govt.

Excellent article, For the first time someone has done an honest assessment of this relationship

Honestly do not understand why this should be so. Corporates were intrinsic to the Gujarat model. The BJP has always been business friendly, not instinctively left of centre or socialistic. Beyond what electoral compulsions dictate. If a reset has become necessary, it should be taken up in right earnest. There can be no sustained economic growth or job creation without India Inc being at the heart of it.

Invest in India at your own peril. Indian citizens are trusted more in foreign countries than in their country of birth. Far easier for an Indian to set up and run businesses abroad then in India. Here not only is there mistrust but also extortion and harassment, courtesy state and central governments. Added to this the government itself runs firms becoming both competitor and rules maker. Who in their right mind would want to invest in India?