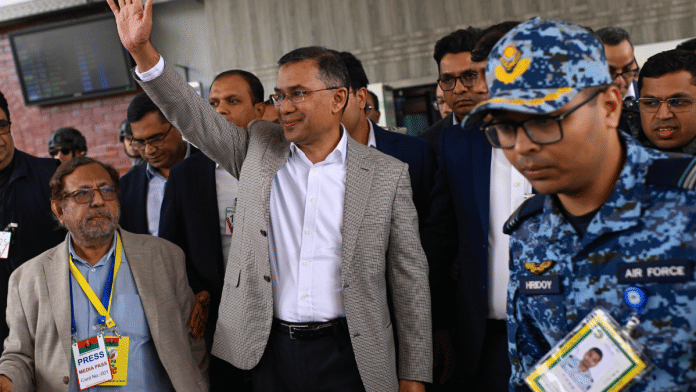

After spending 17 years in London, Tarique Rahman, the eldest son of Bangladesh’s former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia and the acting chief of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, has finally returned to the country during significant political turbulence. In this period of self-exile, Rahman not only got shelter in London but also legal protection, which made it possible for him to perform his political activities from afar.

Political asylum or shelter has been a powerful tool in the hands of powerful nations. It is often projected a moral responsibility or humanitarian nicety toward the endangered. Practically, though, it is more than even diplomatic courtesy. It is a calculated statement by the powerful in the hierarchy of international politics.

To grant shelter to a deposed leader is to proclaim oneself in the international pecking order—one must have enough ballast to absorb the diplomatic shocks and strategic complications that come with it.

Quietly and imperceptibly, political shelter served as a measure of power in the 20th century and after. It became part of a shrewd political lexicon during the Cold War era, primarily through the United States and the United Kingdom.

The role of global powers

The American decision to provide shelter to Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi following the Iranian Revolution was framed in humanitarian terms. But it was also a message to American allies and partners that their loyalty would not be easily forgotten or disregarded. It did prove quite costly to host the Shah, as reflected in the seizure of the American embassy in Tehran, an incident projected as the humiliation of a superpower. Notwithstanding the fact that the Carter administration later prompted him to leave the US for exile in Panama, an initial refusal to grant him shelter would have led to accusations of strategic capriciousness on the part of Washington.

Britain’s role as a refuge to the politically expelled and homeless was also premised on a similar logic, perfected by imperial custom and post-imperial requirements. London became a waiting-room for many deposed monarchs and dethroned prime ministers who had all the hopes of returning to their homelands. The exile of former Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto to the UK during political convulsions, and that of King Constantine II after the end of the Greek monarchy, shows the sense of trust Britain aroused among the beleaguered.

Even though the empire had shrunk, the privilege to shelter had not. The political audacity to offer refuge to dissident leaders—many from its former colonies and others suffering from Soviet oppression during the Cold War—was Britain asserting its position as a guardian of peace and a responsible power, even after losing imperial glory.

France and Saudi Arabia, which showed different moral and ideological scales, were playing the same game. When the French government offered sanctuary to Jean Claude Duvalier following his ousting in Haiti, it was cynicism dressed patronisingly in ‘temporary exile’ or as an unacknowledged presence. Saudi Arabia’s hosting of brutal tyrant Idi Amin had a more transactional rationale.

The exile of former Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in 1999 and 2017 carried the unspoken claim of Saudi Arabia as a regional heavyweight, and its ability to pause a political life, preserve it, and eventually release it back into circulation. The same pattern was followed after Ferdinand Marcos’ regime had collapsed in the Philippines, when the US decided to accord him a safe haven. Similarly, the Narsimha Rao government had agreed to give refuge to former Afghan President Mohammad Najibullah, but Pakistan’s ISI and some Afghan warlords blocked his escape.

Russia’s policy of giving shelter to former allies is also sometimes couched in the language of humanitarianism, even though it is unapologetically tactical. Recently, despite failing to keep him in power in Syria, the Kremlin’s position as the guarantor of Bashar al-Assad is a reflection of Moscow’s position as a key arbiter in regional conflicts. After he was deposed in Ukraine, Viktor Yanukovych was also sheltered in Russia. With this move, Moscow clearly signalled its rejection of the political outcomes under the influence of the West.

The American tradition of admitting overthrown rulers brings out the more intrinsic anatomy of hegemony. Refuge or shelter, in the hands of Washington, has been a sort of temporary safe detention. It enabled the US to carve the post-regime narratives or to guard its human and symbolic assets besides denying its adversaries the pleasure of total triumph. This practice invited accusations of hypocrisy, particularly when the sheltered were accused of corruption or oppression in their home countries. The truth remains that hypocrisy in such cases is not a deviation but the norm.

Also read: A slugfest is on in American Right. MAGA is preparing for the post-Trump era

A more confident India

Both superpowers and rising powers have to manage the contradictions between the norms they profess and the economic and political interests they must protect. In other words, acquiring power alone is not sufficient; one has to wield it even when doing so becomes inconvenient.

India’s move to admit Sheikh Hasina after political upheaval in Bangladesh has to be interpreted in the historical context of its strategic culture. Despite offering shelter to the Dalai Lama in 1959 on ethical and cultural grounds, India has been balancing moral responsibility with strategic restraint during much of its post-Independence history.

Wary of provoking destabilising repercussions, New Delhi has been cautious to the point of being coy in its thinking on sheltering embattled leaders. Ambiguity has been its preferred approach. That caution appears to be eroding now, as India’s power and presence have been increasing in the international system due to rising economic strength and diplomatic reach. By showing a greater willingness to give shelter to its former allies, India can send a message of recalibration in its position from a cautious actor to a self-conscious power.

But there is an important difference between overt refuge and secret harbouring, as they belong to entirely different moral and political worlds. Often, the most obvious demonstration of authority is visibility. Acting openly and showing willingness to stand outside scrutiny and criticism is a sign of power and an expression of sovereign confidence. The fact that Pakistan had been secretly sheltering Osama bin Laden was not a case of tactical brilliance but evidence of strategic bankruptcy, institutional decay, and a political culture ridden with subterfuge. Secrecy in such cases never adds to stature. Plausible deniability does not always raise the status of the state.

Historically, shelter and refuge have never been about compassion or power. Since the time of the Cold War, Western powers have been actively giving refuge to ousted rulers, revolutionaries, and strongmen when they claim to subscribe to the principles of democratic accountability and national sovereignty. It was not hypocrisy but a key characteristic of hegemony. Moral flexibility that is selective and situational has been a critical tool in coping with an international system that is characterised by instability and competing legitimacies.

It is an error to assume that asylum is a moral failure in the logic of power. It would be better to interpret it as an expression of hegemonic capacity: the skill of balancing ideals with necessity, principles with prudence, and morality with survival. Only those states can bear the burden of such decisions that are confident of their place in the international hierarchy.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)