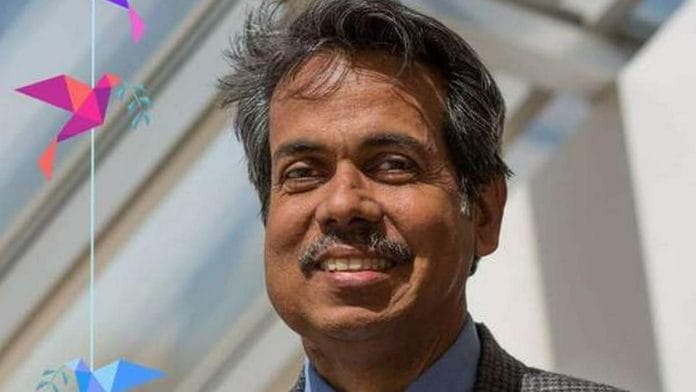

The 205-year-old Indian Museum, the most prestigious nationally and, quite possibly, in Asia, has been in the midst of a #MeToo storm and other irregularities. At the centre of these allegations is the former director of the museum, Rajesh Purohit.

Purohit is not new to controversies. During his earlier job as the director of Allahabad Museum, there were already FIRs registered against him. Run-ins with the museum union, fraud and rough treatment of employees were all part of his career path. The latest being sexually inappropriate behaviour with a female intern in June 2018, an FIR for which was filed two months ago.

The Kolkata media has covered it in a piecemeal and mechanical fashion without analysing the multitude of controversies lying beneath the dignified exterior of the institution. The Times of India has published articles on both his controversial appointment of a Hindi translator as museum head of security and the sexual harassment case. Anandabazar Patrika also published a story on the harassment charges and quoted Purohit saying that he did not know the complainant. Most of these reports were tucked away and never made it to the front pages.

The Indian Museum in Kolkata was founded in 1814, and is the largest and oldest museum in India. It houses over one lakh artefacts, including Asia’s only ‘resident’ Egyptian mummy, which is over 4,000-years old.

And yet, the culture ministry in New Delhi, to which it reports, has not taken any action against Rajesh Purohit except for transferring him back to the Allahabad Museum last week.

Museums play an important public interface role, and yet the ministry does not appear to be applying basic HR practices for its staff, and looks the other way even as India’s oldest museum gets engulfed in a criminal scandal.

“Museums may have been important in the past to showcase a city, but today they play an important link – a connection to the past for the new generation. The latter, mainly on account of the new syllabus and style of scoring rather than learning, are delinked from the cultural richness, the wonder that was India and, sadly, bereft of the knowledge of their own heritage,” said Rajiv Soni, a Kolkata historian and retired Tata Steel executive.

But what if museums fall into the wrong hands?

Also read: #MeToo wasn’t the first: Women-led movements aren’t new, especially in India

Run-in with the law

Rajesh Purohit’s run-ins with law were recorded as early as 2014. He was the Director of the Allahabad Museum at that time, and found himself at the Allahabad High Court answering charges of having “made false averments” in an affidavit to the court when it was looking into an alleged fiddling of payments made to cleaning staff at the museum. The order said he manipulated records to “mislead the Court for gaining moral victory over a poor employee”. The Allahabad High Court placed Purohit under watch for three years. In 2015, Purohit tendered his apology “with folded hands” before the court.

Criminal proceedings were nothing new to Purohit, he had as many as six charges against him in 2013, the outcomes of which are unclear.

While Purohit was in Allahabad, Keshari Nath Tripathi was an Allahabad High Court senior advocate.

Interestingly, even though the Allahabad High Court had ordered that Purohit be kept under watch, the Union Ministry of Culture saw it fit to make him the director of the Indian Museum during this period.

When Purohit moved to the Indian Museum, Tripathi had already become the governor of West Bengal.

Tripathi’s new role included being the chairman of the Board of Directors at the Indian Museum. Over 35 applications were received for the post of director of the Indian Museum, intriguingly the only candidate to be interviewed for the post was Rajesh Purohit, say sources. And he was subsequently appointed by Governor Keshari Nath Tripathi on 1 September 2017.

Also read: Not just Modi’s museum for PMs, Indian MPs need archives and oral histories too

New director, new controversies

Purohit started his new role with great enthusiasm. “It gives me immense pleasure to become part of one of the largest and oldest encyclopaedic museums in Asia as the Director,” he wrote on the Indian Museum website.

Here, too, Purohit’s controversies continued.

The unions were unhappy with some of his decisions like “unlawful transfers, layoffs, threats”. He even suspended five staff members, without reason, claimed the workers’ union. But the Calcutta High Court later reinstated them in August this year because it found that Purohit had no authority to remove them.

Purohit was also criticised when in April this year he removed the head of security of the Indian Museum, a retired Kolkata Police officer, and replaced him with the museum’s Hindi translator, Ashok Tripathi, who was given dual charge.

“Indian Museum has 171 vacant posts. I don’t have an officer for the job and the museum director has the authority to designate a person for any job he deems suitable for the person,” Purohit was quoted as saying.

Staff also complained about Purohit’s wife Sharmila Purohit, who had no official post or job at the Indian Museum, but often took part in or even chaired meetings with the staff.

When the family of late Indian Museum director and Padma Shri awardee Asoke Bhattacharya appealed to Purohit to have his long-overdue pension paid, which by now had amounted to over Rs 50 lakh, Purohit allegedly refused.

More allegations

New Year’s Day 2016 saw two bright young Presidency College (now University) graduates join the Indian Museum as interns. Writh Barua was assigned to the publications department while Sonia Sharma (name changed for legal reasons) joined the education department.

The harassment began in 2017 when Purohit joined as the director. Purohit would allegedly summon Sharma to his office repeatedly for ‘meetings’, some of which went on for over two hours and included her being asked about her marital status with his eyes roving over her breasts. These meetings were closed-door, with no one else present in the room.

On the other hand, Barua too had to face Purohit’s excesses. He would call Barua a “launda (lad)” in conversations. On 11 October 2017, Writh Barua went to the director’s office. Purohit, displeased with Barua’s work, allegedly threw a file at him. Barua told Purohit that such behaviour was unbecoming of his post and totally unacceptable. Barua walked out of the museum and his job, never to return. He wrote several letters to governor Keshari Nath Tripathi, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the Ministry of Culture, All India Federation of Bengali Buddhists and the Scheduled Tribes/Scheduled Caste Commission, copies of which are with ThePrint. Barua is a Bengali Buddhist, who comes from a Scheduled Tribe. No one replied.

Also read: The art of ruining a world-class exhibition, brought to you by the National Museum

Things turn uglier

According to Sharma, in June 2018, Purohit allegedly summoned her to his office on the pretext of asking her what she was working on – a series of images which she was told to put on a USB stick and bring with her. Sharma had finished her internship and had joined the museum through an agency as a junior conservancy officer in 2017.

He was waiting for her alone. When she presented the USB stick, Purohit allegedly asked her to come around to his side of the ‘L’ shaped desk and insert the device herself. Bent over the desk while inserting the USB, Sharma felt Purohit place both his hands on her butt. Without reacting or saying a word, traumatised and shocked, Sharma walked out of his office.

Sharma claims it was her refusal of his sexual advances that bothered him. After the sexual assault, Sharma was moved to the education department and a mental harassment campaign began against her, allegedly engineered by Purohit.

At first, she was given no work. Then she was excluded from the education department programmes for the public. Finally, she was allegedly told that her contract would not be extended. No formal letter was provided, leaving her with a void in her resume and hampering future job applications.

Having spoken to her lawyer, she was advised to not remain silent about the sexual assault any longer. Sharma filed an FIR on 4 June 2019, a copy of which is with ThePrint. Her lawyer further advised her to go to the museum to ask for her termination letter.

On the sexual harassment allegation, Purohit said, “Police are investigating the case, which is already in court. So it is not advisable for me to speak on the matter.”

Later in June, the West Bengal Commission for Women took cognisance of the sexual harassment complaint. It asked the Indian Museum to probe the complaint.

On 2 July, Sharma decided to visit the Indian museum to get her termination letter. At the main gate, two museum staff and three women security guards allegedly assaulted her. They told her that the director had asked them not to let her in. A senior member of staff saw the commotion and stopped it.

The chargesheet filed by Kolkata Police states “…one letter of complaint against the Director of the Indian Museum Shri Rajesh Purohit to the effect that FIR named accused person voluntarily used criminal force upon the complainant, a female intern of Indian Museum by means of unwanted physical contact and unwelcome and sexually coloured remarks intending to insult the modesty of a woman and thereby outraged her modesty inside Indian Museum”.

“I have also got a complaint of trespassing from the security officer Joydeep Das. I have constituted a five-member probe committee. They will check CCTV footages and submit a report, on the basis of [which] action will be taken,” Purohit told The Times of India.

Finally, on 4 September, Rajesh Purohit was transferred back to Allahabad Museum with a new director taking charge at the Indian Museum.

ThePrint reached out to Rajesh Purohit for his comments. This article will be updated as and when he responds.

Also read: “Museum wahin banayenge!”

A ‘megalomaniac’

It seems surprising that ever since Purohit first found himself in trouble with the law back in 2013, right through to the allegation of sexual assault a few months ago, the Ministry of Culture seemed to have been utterly oblivious to the kind of conditions their staff are being subjected to and the seriousness of the allegations against senior staff.

Purohit’s clearance for the Indian Museum job would have been rubber-stamped by the ‘Appointments Committee of the Cabinet’ (ACC). The ACC can take anywhere from four months to two years to clear people for the job, with senior sources saying the inputs required by the current government include not only their standard resume and qualifications, but a grey area known as their ‘360 degree Pen Picture’, which will be information gleaned about the candidate by the Intelligence Bureau and the Central Bureau of Investigation. All of this is beyond the remit of the Right to Information Act.

Jawhar Sircar, a retired IAS officer whose last posting was as the principal secretary, Union Ministry of Culture, said: “I know Rajesh Purohit well, he is a highly repulsive man, a megalomaniac who is narcissistic to a frightening extent. I recall visiting him at the Allahabad Museum, where he implemented a ‘groupism’ style of management, with his group on one side and the rest of the staff isolated.” He also added that “Purohit’s past should have come to our notice.”

Who will watch the watchmen?

Purohit was abruptly transferred back to Allahabad on 4 September. It came a few weeks after Keshari Nath Tripathi retired as governor of West Bengal and was replaced by Supreme Court senior advocate Jagdeep Dhankhar, who also took over as the chairman of the Indian Museum.

The new director, Arijit Dutta Chowdhury, took charge on 4 September.

Under him, the CRPF will now manage the security of the museum, without any dual charge responsibilities.

A senior source in the Ministry of Culture told me the new director “wants to clean up the mess”.

Museums are not just places for the public to see artefacts, they are the nations repositories; places where intensive research and restoration take place to better inform the country, and the world, about our past.

Most of the world’s most valuable, and often invaluable, treasures are held not in banks or vaults, but in our museums. The caretakers of these have a responsibility not to the ministry, but to humankind. Our governments must work harder to ensure that the hands that hold the nation’s past are beyond reproach.

The author is an ex-Scotland Yard officer based out of London and Kolkata, and works as a historian and writer. His writings focus on governance, policing and politics. Views are personal.

Well this is the sorry state of affairs in the Culture Ministry. There are numerous complaints against autonomous organisation such as Lalit Kala Academy, Sangeet Natak Akademi etc. Who are located right under their nose. However no action is deemed necessary by the Ministry.

The level of corruption has no limits and rules and regulations are flouted with impunity. God save this country, which I doubt will.

What is new in this story , reverends of the pope do it , people called ‘ bapu’ do it , poor ram and Rahim too got embroiled due to gur meet god . When these kind of stories emerge , it is often a case of , things having gone too far and not the men in authority doing the right thing .Men , powerful men , or all the men who aspire to it sometimes must believe they are god reincarnate (megalomaniac).

Shocking