It was easy to call it Scariana Airways. Ariana, the Afghan national carrier of yore, had a style entirely its own. So, almost everybody who has flown with it has a scary story or two to tell. On the 40th anniversary of the Soviet invasion, which began a war that’s never ended for the Afghans, I’m inflicting on you some scary stories of mine.

On which other airline would you have seen a flight steward struggling with a kerosene cooking stove — the kind that sometimes ‘sorts out’ young brides who brought ‘inadequate’ dowry. It was on a flight from Delhi to Kabul when Najibullah was under siege and rockets sometimes landed on the airfield just when a plane was landing or taking off.

“Now what the hell are you trying to do?” I asked.

“The captain wants tea. The hotpoint kaput. No work. Russian plane, you see,” said the steward, and continued pumping the stove.

“But you will kill us,” screamed a German photographer.

“Nothing will happen. Inshallah,” said the steward.

There were other things for which you couldn’t even blame an over-enthusiastic flight steward. An Ariana Tu-154 we were on was approaching the runway when the pilot pulled up abruptly, nose in the air, the three already overworked engines straining to keep the belly from kissing the Paghman ranges. The plane made an emergency climbout to evade the mujahideen rockets, we were calmly told. You held on to the backs of your seats, your feet jammed under the one in front so you wouldn’t topple over backwards. The pilot flew straight back to Delhi.

But nobody let you take your bags and go home to safety. An hour in the transit lounge and you were back on your way to Kabul again. The rockets, we were told, had stopped falling. And Ariana wasn’t going to lose revenue just like that.

Aviation in an Afghanistan in the throes of the so-called jihad was more than just the usual Afghan devil-may-care bravado or ‘Inshallah’ fatalism. It also underlined the Afghan spirit of adaptation and survival. The roads had already been bombed out. In any case, every 10 miles were controlled by a different commander (read, thug), and you could spend a lot of time merely paying tolls or organising a ransom. Airplanes were the only reliable mode of travel between cities, if you could afford it. It also made internal flights within Afghanistan even more interesting and adventurous.

On a visit to Herat on a beat-up An-26, you would have the distinction of using the most unusual mode of transport even for your airport pick-up and drop — a Soviet BMP-I Infantry Fighting Vehicle. Anything less would not have been able to negotiate the drive, which was no more than mine and grenade holes.

Even the tracked BMP bounced and you held on to the next protrusion, or even the next guy’s belt, for dear life. And then you flew back after dusk, the horror show of a lifetime.

First of all, the An-26 was overloaded at least twice over, and there was good reason for it. All of Herat had seen a passenger aircraft land, so a lot of Herat had lined up at the airbase in the evening, hoping to find a ride to Kabul. The pilots were first class free-marketeers.

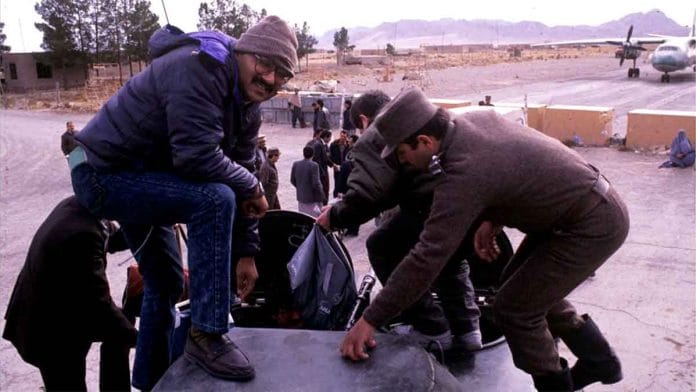

They stood next to the aircraft, collecting their tribute and letting passengers in. No tickets, no boarding passes, no baggage checks, no claim checks, and finally, no frisking or security checks. It was a cash-and-carry flight. The cash was being stuffed into two gunny sacks — it was already several hundred afghanis to a dollar, and with a black market on larger notes, a passenger sometimes paid several kilos of currency to get his family on board. It’s also not as if all their baggage required a security check. Many carried just blankets, some had goats, one had chickens clutched under his armpits.

Also read: The violent, self-destructive legacy ISI chief Hamid Gul leaves behind

Because the pilots wouldn’t say no to anybody and because the stream of passengers was never-ending, we were not able to take off until well after sunset which, apparently, was against the regulations. And the airstrip had no lights.

“Don’t worry. We’ve been doing this for years,” said the pilot, who couldn’t be more than 20-22. Maybe the Afghans let them fly before they were old enough to get driving licences.

We took off, packed like, well, Afghans on an internal flight. Goats, chickens, two Afghan generals, three Russian advisers, too many journalists, and all. As the wheels left the ground, one general took out the Quran and started to pray. The Russians pulled out a bottle of vodka and “killed” it among the three of them before we were even 10,000 feet in the air.

If there were no lights on the runway for the take-off, there were none allowed inside the plane either. You don’t want to tell some Mr Fast Fingers with a Stinger missile where to fire. In any case, there was no place for anybody to move a muscle. Until an Afghan decided to have a smoke and struck a match. An air force corporal scrambled past several passengers, baggage, sent the chickens flying, and grabbed the delinquent passenger kicking and screaming. He sure had public opinion on his side. We turned instantly into a mob, and blows rained on the poor smoker from all over, though who was to know where exactly they landed.

The pilots actually had a sense of (very dark) humour. After what looked like the longest hour of your life, the plane landed at an airfield where lights came on only for a moment for the touchdown and proceeded to a deserted corner of what was a graveyard of aviation — the place where they stored wreckages of planes shot down by the mujahideen Stingers. The rear hatch opened, most of the Afghan passengers descended and proceeded straight to the corner where the steel-framed fence had been cut. We waited our turn. But the hatch closed, the plane began to taxi again and the captain, the same self-proclaimed veteran, announced that this was Jalalabad and we were taking off for Kabul again. Jalalabad, at that juncture, was the zone of heavy fighting between the mujahideen and Najibullah’s forces.

But the pilot, obviously, wasn’t so sure of our nerves, so he didn’t push that cruel joke further. We just taxied to the other end of what was indeed Kabul airport, and then to the real arrival lounge. We figured then that it was just that he had to first offload his ‘private’ passengers and the gunny-sacks full of cash in a safer place.

There are other stories, some dangerous, some quaint. Landing at Mazar-e-Sharif once with a Newstrack crew that then carried a hundred kilograms of equipment, we found no porters, no transport. I grabbed the first Afghan I found, dishevelled in crumpled khakis, and asked if he would give a hand for 10 dollars.

“Me, peelaut (pilot),” he said. “Me no carry baggage.” He also pointed to the plane he flew, a MiG-27, parked fully armed. Ajmal Jami and Bharat Raj, who grew into famous cameramen for NDTV later, would testify to that story and might even send me and photographer Prashant Panjiar 10 dollars for carrying their baggage, as we could claim no exemption as “peelauts”.

The real surprise, however, was how could a place so backward, so primitive, have so much aviation? But that was so true of Afghanistan in so many ways. How could a place as poor, rundown and traditional as Kabul, for example, have so many short-skirted women? Or, how could a society so Islamised, so caught up in a jihad and owing so much to the Pakistanis, have so much affection for India?

Don’t buy the usual Kiplingisms on alleged Afghan disloyalty and deceit. If you live on a land which produces so little, is surrounded by giant hostile neighbours, is hundreds of miles from the nearest port, has no oil, no industry, is an unwitting pawn in a centuries-old Great Game, and boasts of nothing else than warfare as its main source of employment, you learn to adjust and adapt, take risks, believe in God. They can do nothing about the neighbours. But they have learnt, over the decades, to let their imagination leapfrog a bit and look at a more distant neighbour, India, for political and cultural linkages and succour. The Afghan affection for India has a strong emotional side.

But there is more to it than mere emotion. India may be a slightly distant neighbour, but it is the only one with no territorial, cultural or political designs over Afghanistan. It also has the strength to balance out the others, particularly Pakistan, which has always held Kabul in contempt.

Afghanistan is also a land of mega paradoxes. It defeated the Soviet power, a feat big enough to end the Cold War, finish the Warsaw Pact and bring down the Berlin Wall exactly 10 years after the Soviet invasion. But, a full 40 years after that freezing day in 1979, when the first Soviet tanks crossed the bridge on Amu Darya (Oxus river) from what was then Soviet Uzbekistan, Afghanistan is still at war with itself. It is also still a battleground and victim of big power rivalries, too.

Also read: The major miscalculation by US in its Afghan war — Pakistan

Awesome, Shekharji. I enjoyed reading and laughed out loud along the way.

+!