The political project called Hindutva has always faced a foundational contradiction: claiming inclusiveness while firmly practising exclusion. The necessity of moral and cultural legitimacy requires it to be broad based — so that it can claim the entire civilisational heritage of India. Yet, its political compulsions push it towards narrowness —so as to forge a political community of only one, albeit majority, religious denomination called the Hindus.

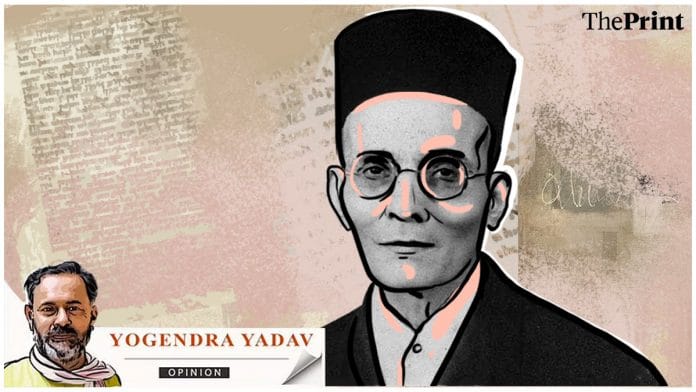

Is there a way out of this difficulty, except sheer hypocrisy or moral cussedness that characterises much of the politics of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its associates these days? The first full-length, meticulous and non-partisan intellectual biography of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar that came out last month seeks to persuade us that Hindutva is an ideology that we must learn to engage with in all seriousness. In doing so, the book ends up revealing theoretical confusion, historical obfuscation, political ambivalence on colonialism and moral sanction of violence that is inherent in this ideology.

The contradictions at the core…

Let us first understand the basic contradiction. Like all nationalism, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (and earlier, Hindu Mahasabha) version must claim the civilisational glory of pre-colonial India by locating India’s nationhood in time immemorial. This intellectual project faces two obvious difficulties. If you define Indian nation to include all the cultures and communities before the capture of power by the East India Company, the Indian nation must comprise a vast range of cultures, communities and religious denominations. Besides the Hindus, it must include not only Sikhs, Jains and Buddhist, but also Muslims and Christians living in India for centuries before the advent of colonialism. The second problem is about the indigenous communities that pre-dated the rise of what we today call Hindu religion. Should they not have primary claim to India’s nationhood?

So the problem is stark: if the cut-off line for pristine nationhood is drawn too late, it must include Muslims and Christians. If it is drawn too early, it must exclude the Hindus. Both of these defeat their political project. How does one claim India’s nationhood for the Hindus without falling into either of these traps? Savarkar’s concept of Hindutva is an innovative response to this challenge. His entire body of work — spanning across genres (poetry, drama, history, polemics), languages (Marathi, English), locations (London, Andaman, Maharashtra) and of course political phases (pre-Gandhi, Gandhian and post-Gandhi) — is an attempt to write a series of histories: of the Indian nation, of the Marathas and of himself. His one-point agenda in all this is to defend the political claims of Hindutva.

This is the thread that runs across Hindutva and Violence: V. D. Savarkar and the Politics of History by Vinayak Chaturvedi. Did you notice the coincidence in the first names of the author and his protagonist? Yes, he was named after Savarkar (no, he is not from an RSS family) by his paediatrician, Dr. Dattattrey Sadashiv Parchure, one of the nine persons accused and tried for the murder of Mahatma Gandhi, and one of those who managed to get away by fibbing. The author narrates the fascinating story of how he discovered this connection when he was an adult, after Dr Parchure passed away.

This uneasy bond defines the tone of the book. This is certainly no hagiography, in sharp contrast with Vikram Sampath’s two-volume offering that has been in the news, not for its scholarship but on charges of plagiarism. At the same time, Vinayak Chaturvedi does not follow the dismissive and denunciatory approach followed by most of the secular historians and commentators. He is careful, a tad too anxious, about not judging Savarkar. He does not interrogate his subject hard enough. He is too circumspect to pierce open the apparent contradictions in Savarkar’s thought. Yet his immaculate scholarship and deep probing of Savarkar’s text offers many strands that weave into an argument.

Given his focus on ideas, it is understandable that he refuses to be drawn into most of the controversies surrounding Savarkar that have made headlines of late: Was he a ‘veer’ or a ‘maafiveer’? Was he being brazenly self-promoting when writing his own hagiographies under pseudo-names? Was he directly complicit in the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi? On balance, Chaturvedi takes a sympathetic view of Savarkar’s conditions and pleads for not looking at him through the spectacles of present-day politics. Throughout this 480-page book, he manages to keep the focus firmly on Savarkar’s political theory rather than his political action.

Also read: Best way to celebrate Bhagat Singh—rescue his memory from meeting the fate of Gandhi, Nehru

And the solution Savarkar found…

So, how does Savarkar resolve the theoretical contradiction? In the first phase of his life, he did not have to. Savarkar’s first major book, a retelling of the story of the “mutiny of 1857” as the First War of India’s Independence, was very much within the inclusive nationalist frame. In fact, he says: “So, now, the original antagonism between Hindus and Mahomedans might be consigned to the Past. Their present relation was not of rulers and ruled, foreigner and native, but simply that of brothers with the one difference between them of religion alone. Their names were different, but they were all children of the same Mother; India therefore being the common mother of these two, they were brothers by blood.” Savarkar went on to say that for Hindus to nurse hatred against Muslims now was “unjust and foolish”. But after his incarceration in Andaman, Savarkar was a changed man. His book Essentials of Hindutva, first published in 1923, laid down the foundations of an exclusivist ideology of Hindu nationalism that he lived with till the end.

His solution to the problem of defining Hindus was innovatively tailored to the political project. Hindus could not be limited to the followers of Hinduism – that would make Hinduism tamely mimic the Western concept of religion; it would also entail excluding Sikhism, Jainism, and Buddhism from the encompassing fold of Hinduism. According to Savarkar, you are a Hindu if ‘Hindusthan’ is your matribhoomi (motherland), pitribhoomi (fatherland) and punyabhoomi (sacred land). Motherland is a geographic concept and covers everyone who has lived within India’s territory. But that would cover people from all races, religions and communities. Fatherland helps to narrow it down, as it limits the community to those who share ties of blood with one another. But this would still not exclude those whose ancestors converted to Islam or Christianity. Hence Savarkar’s final condition: only those who believe in this land as their sacred land (no Mecca, no Jerusalem) as well.

What about those who have lived in this geographical area before ‘Hindus’ arrived here? This was a serious issue with Savarkar, since he accepted the idea that Aryans brought Vedic culture and civilisation to India and was anxious to prove that Hindus are not dark skinned. He is blunt on this point: Yes, Hindus conquered the original inhabitants violently, but they assimilated into Hindu culture. There was no rebellion, no lingering resentment. They are all Hindu now. So were those outside India who came under Hindu cultural influence. Savarkar was opposed to British colonialism, because it was European, not because it was colonialism. He was quite an enthusiast for Hindu imperial expansion.

Does that make for a coherent ideology? Not quite. This book shows that Savarkar could never offer a clear definition of Hindutva. Instead, he resorted to history, what he called “a history in full”, to show what Hindutva was. Is his grand retelling of India’s history factually accurate? No serious historian has found it possible to agree with Savarkar’s footloose and conjecture-full concoction of Hindu history. Certainly not the historians who take Adivasi and Dravidian pasts seriously. Can this ideology claim moral high ground? Not unless it explains why the moral concession that Savarkar grants to violence by the Hindus to their predecessors should not be extended to the Muslim invaders and British colonial power. But then the raw emotional appeal of Hindutva has never depended on these subtleties. There is no intellectually honest way past the foundational challenge to politics of Hindutva. You can paper over the foundational contradiction, but you cannot resolve it; you cannot capture India’s rich civilisational heritage for one section of its people except through subterfuge or fraud.

Were Vinayak Damodar Savarkar’s elaborate stories and theories, then, a thin ideological wrapping for a political project of exclusion, resentment, hatred, bigotry and violence? Vinayak Chaturvedi does not offer such a direct argument. But the material he presents in this must-read intellectual biography leaves us with no other conclusion.

Yogendra Yadav is among the founders of Jai Kisan Andolan and Swaraj India. He tweets @_YogendraYadav. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)