The Reserve Bank of India last month undertook a massive clean-up exercise in banking regulations. It consolidated its own instructions spread across thousands of separate circulars, directions and notifications into 238 Master Directions.

The drafts of these directions were published for about a month on the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) website for public feedback. In this clean-up process, it ended up withdrawing 9,400-odd instructions issued by it since the 1940s. These three steps—the consolidation of instructions, the public consultation process, and the mass repeal of instructions—are positive steps. They signal the will and potential zeal on the RBI’s part to simplify regulation in Indian banking and make it more accessible to the banks themselves, their depositors and borrowers and the layperson.

That said, the sheer scale of this clean-up behooves us to consider the regulatory cholesterol that has accumulated in the Indian banking space, ask why this is the case, and how we can keep unclogging banking regulation without compromising on the governance of banks.

Build-up of regulatory cholesterol

The Parliament delegated significant powers to the RBI to regulate Indian banks almost immediately after independence. The law empowers the RBI exclusively to lay down ‘banking policy’ for India and issue “directions” to banks generally or to any bank in particular. These directions may pertain to a wide range of matters, such as the purposes for which banks may lend, the margin of collateral they must maintain against every single loan, interest rates or other terms and conditions of lending.

More broadly, the law empowers the RBI to issue any direction “as it deems fit” in the “national interest” or “to prevent the affairs of any banking company being conducted in a manner detrimental to the interests of the depositors or in a manner prejudicial to the interests of the banking company”, or somewhat more widely, to secure “the proper management of any banking company generally”. Contrary to popular perception, the RBI could exercise such direction-making powers over both private and public sector banks.

The 9,400-odd instructions that the RBI withdrew last month were issued in exercise of these ‘direction-making powers’. These directions were not issued in a standardised manner, but took the form of Master Directions, Master Circulars, Circulars, Notifications, Guidelines, and Press Releases. For the most part, there was no uniform process of approval or internal scrutiny for issuing these instructions, with each department following its own operating procedures.

Such directions could be issued, implemented or withdrawn overnight, amended partially or wholly once they were issued, and could be applied to a particular bank, a few banks or all the banks. The law does not obligate the RBI to make these directions public, with the result that one could never tell if the publicly known directions were exhaustive or not.

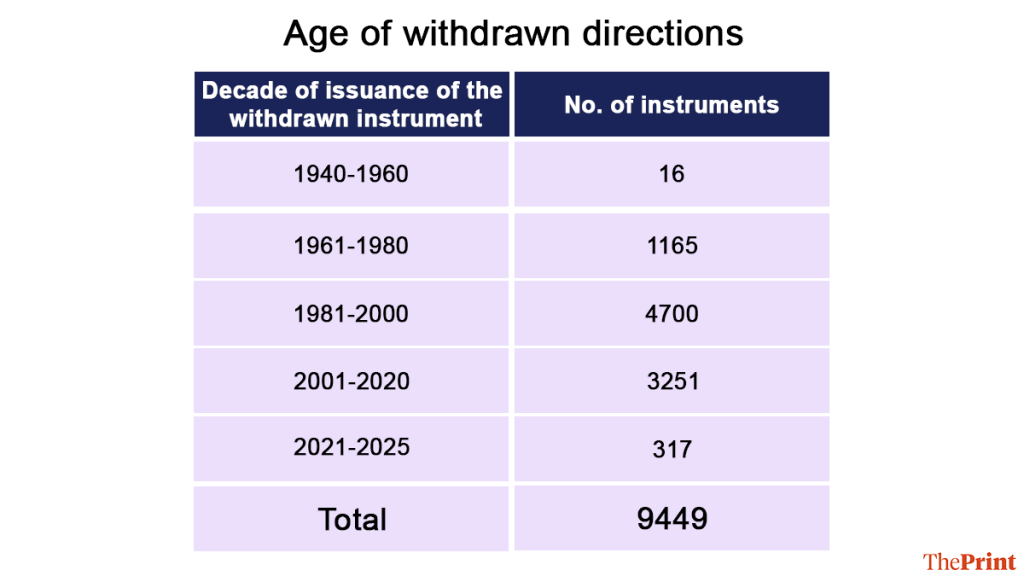

With such wide discretion hardcoded in the Banking Regulation Act, the regulatory cholesterol in banking had built up over a long period of time. A few of the instructions that the RBI withdrew in last month’s clean-up can be traced to 1944, when the Banking Regulation Act did not even exist. Several others from the 1950s and 1960s pertained to the planned credit era of banking in India, a regime dismantled 35 years ago.

Yet, not all the clean-up pertains to old instructions. More than 75 per cent of the withdrawn and consolidated instructions were issued in the 40 years between 1980 and 2020. This implies that even after the liberalisation reforms of the 1990s, the RBI continued to indiscriminately use its direction-making powers to control and manage Indian banks.

Also read: India is trying a new China strategy. It’s called ‘managed rivalry’

The long road ahead

We often take the imperative of regulating commercial banks and the complexity of banking regulation for granted. Banking regulation is, in fact, a relatively recent phenomenon, traceable only to the mid-20th century. Prior to the 1930s, banks were clubs, licensed by governments but hardly regulated, if at all.

Three phenomena made banking regulation as complex, voluminous and omnipresent as it is today—the financial crisis in the US in the 1930s, increasing financialisation of savings, and the eventual global interconnectedness of banking from the late 1980s that drove the Basel agreements’ standard-setting role for banking regulation worldwide. Amidst these developments, a key principle of keeping the law simple and accessible to those governed by it got missed.

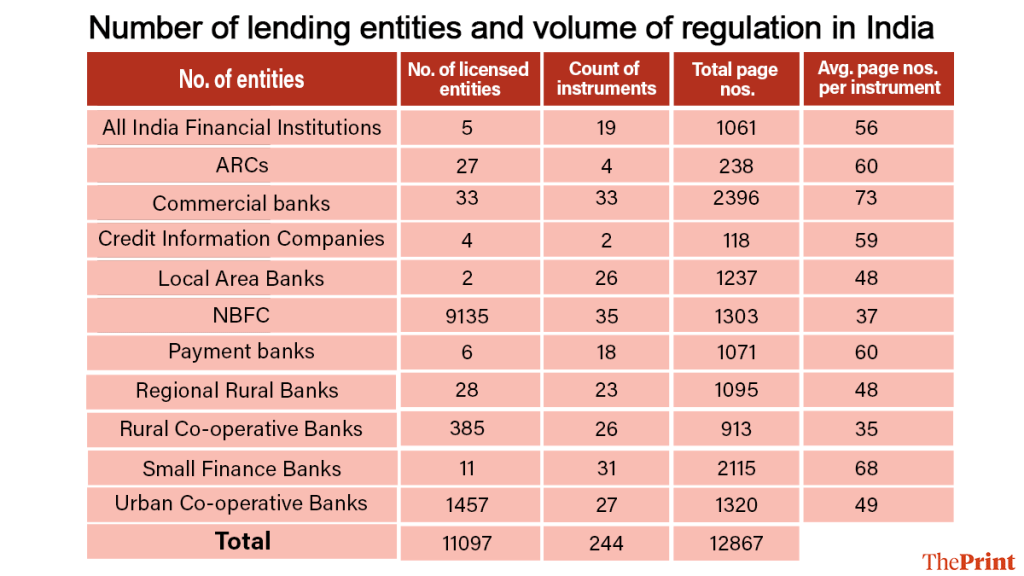

This played out in India, too. We have a few formal lending institutions and more regulations (Table 2). Despite the RBI’s consolidation exercise of last month, the RBI’s directions to lending institutions in India aggregate to at least 13,000 pages. Five financial institutions continue to be regulated by 19 instruments aggregating to more than 1,000 pages, 26 instruments running into 1,200-odd pages are dedicated to two local area banks, and 31 instruments aggregating to more than 2,000-odd pages govern all of 11 small finance banks.

Also read: Why RBI’s liquidity push matters more than the rate cut

Systematic periodic reviews

Last month’s clean-up exercise made a start, but much needs to be done to make a dent in simplifying banking regulation in India.

Two directions of reforms are immediately visible. First, the RBI must endeavour to minimise the exercise of its direction-making powers to micro-manage banks. The most obvious example is to dispense with the detailed directions on the minimum age, qualification, expertise and remuneration-related requirements for directors on bank boards.

Second, as recommended earlier by several governments, the RBI’s own committees, a mandatory sunset clause, which automatically withdraws an instruction after the lapse of a certain duration unless explicitly renewed, must be hardcoded in the law. This will ensure that the clean-up exercise is not a one-time effort, but survives over time and across leadership styles at the RBI.

Bhargavi Zaveri-Shah is the Co-founder and CEO of The Professeer. She tweets at @bhargavizaveri. Views are personal.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)