The Defence Acquisition Council (DAC), chaired by Defence Minister Rajnath Singh, is set to deliberate on one of India’s most significant military procurements of recent times: the acquisition of 114 Rafale fighter jets from France’s Dassault Aviation. The proposal comes amid escalating regional tensions and a critical shortfall in the Indian Air Force’s (IAF) combat capabilities.

The deal is estimated at approximately Rs 3.25 lakh crore (around $36 billion). Under the proposal, 18 aircraft would be delivered in fly-away condition, and the remaining jets would be manufactured in India with up to 60 per cent indigenous content.

The insistence on local manufacturing, incorporating local raw materials and employing local talent is aimed at mitigating the massive cost burden of the deal. The Defence Secretary Rajesh Kumar Singh, while speaking to a media platform on 7 February 2026, indicated that India would drive a hard bargain to extract as much as possible in terms of localisation of content, labour, tech and material.

The timing of the DAC meeting is significant, as it precedes French President Emmanuel Macron’s visit to India later this month for the Artificial Intelligence Summit. This trip could potentially facilitate a government-to-government agreement.

This (likely) procurement has invited significant attention in India and abroad as it comes in the wake of the recent India-Pakistan conflict. Islamabad claimed to have downed several Rafale jets— India laughed it off, calling it imaginary.

Considering the high cost of acquisition, this news has also ignited fierce debates across media, social media platforms, and strategic circles. Two clear and contradicting views have emerged.

On one hand, proponents view the Rafale as an indispensable asset to address urgent operational deficiencies, particularly in the face of a collusive two-front threat from Pakistan and China. The jets’ proven performance, availability of ready infra and trained manpower, make it a “magic bullet” for modernising the IAF’s fleet. Critics, however, argue that the staggering cost, which could potentially exceed $40 billion after including spares, maintenance packages, weapons, and upgrades, could cripple funding for indigenous programmes. It might turn out to be a “poison pill” for India’s desire to create a self-reliant defence ecosystem.

These arguments, while fervent, often overlook nuanced realities, including the IAF’s current vulnerabilities, production delays in domestic alternatives, and the evolving geopolitical landscape. To evaluate the futility or the utility of this mega procurement, we must first define the problem it aims to solve.

Defining the problem statement

India confronts persistent threats from two adversarial neighbours: Pakistan and China, with the added possibility of a collusive pincer. This requires a comprehensive “whole of government” strategy encompassing diplomacy, economic leverage, international alliances, and robust military deterrence. While non-military tools are vital, they are ineffective without credible armed forces, particularly air power, which plays a pivotal role in modern conflicts.

The IAF’s challenges are exacerbated by rapid advancements in Chinese military capabilities and deepening China-Pakistan ties, evident during Operation Sindoor. In this context, the IAF’s sanctioned strength of 42.5 fighter squadrons, each typically comprising 16-18 aircraft, is deemed insufficient. Various studies and reports, including a recently concluded study chaired by the Defence Secretary on enhancing the IAF’s capabilities, have recommended an increase in the sanctioned strength of the IAF fighter squadrons.

The suggested numbers vary from 55 to 65 squadrons, considered essential to handle simultaneous threats. However, as of early 2026, the IAF operates only about 30 operational squadrons—the lowest since the 1960s. This shortfall is compounded by impending phase-outs over the next decade—nearly half the current fleet, including Jaguar, MiG-29, and Mirage 2000 squadrons. This will reduce the strength even more unless adequately replenished.

Thus, the core challenge before the nation is equipping the IAF with adequate numbers swiftly. This is the problem statement and should give us the context for evaluating the upcoming Rafale deal.

Fill rate vs depletion

The “fill rate”—the pace at which new aircraft are inducted—remains alarmingly low. With deliveries of the indigenous Light Combat Aircraft (LCA) Mk1A stalled due to delays in sensor and weapons integration, certification issues, and delayed engine supplies from GE Aerospace, the current fill-rate is effectively zero.

For the record, of the 20 LCA Mk1 (FOC version) aircraft contracted in 2010 and to be delivered in 2016, two are yet to be handed over to the IAF. Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) has promised to improve deliveries in the near future; however, persistent supply-chain issues, besides challenges pertaining to integration and certification, would likely push the delivery dates further.

Even in the best-case scenario, HAL would be able to deliver 24 aircraft per year by 2028. At that pace, it would take us till 2040 to reach the currently sanctioned strength of 42 squadrons (considering phasing out of obsolete platforms in the interim period).

We need a “fill rate” of 40 aircraft per year to reach 42 squadrons by 2035, by which time the Jaguars and the MiG-29 would start phasing out. The desire to provide 65 fighter squadrons to the IAF seems unachievable at this moment. To add insult to the injury, at this stage, our depletion rate outpaces replenishment.

Ideally, the replenishment should come from indigenous sources to foster self-reliance under Atmanirbhar Bharat. However, timelines make this unfeasible. LCA Mk1 deliveries are incomplete, Mk1A delayed, Mk2 yet to fly, and the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA) is at the partner selection stage. The DAC faces a stark choice: endure a “hollowed-out” air force until domestic output ramps up, or import to maintain deterrence.

Therein lies the rub.

The government would need imports to compensate for the delays of domestic programmes; the cost of which would starve the domestic programmes for funds, causing further delays. Critics allege that this decision would hinder LCA and AMCA progress, perpetuating import dependency. Yet, without credible airpower, India risks vulnerability. This dilemma underscores the improbability of relying solely on domestic production for immediate needs, before adequate maturation of domestic capability.

The government is now facing Hobson’s choice. It has to import, or it risks fielding a depleted, hollowed-out Air Force.

Also read: A 2-hour op, precise extradition—what Maduro’s capture tells us about modern US military

Why Rafale?

Another question that comes up during discussions is – why procure a 4.5 gen aircraft with deliveries scheduled to complete over the next 10 years, when your adversary is already fielding 5th gen aircraft!

Our threat environment demands a balanced mix: fifth-generation stealth aircraft for high-end missions and 4.5-generation jets for the bulk of operations. On the fifth-generation front, India is committed to AMCA, with prototypes promised by 2028 and serial production by 2035.

Among the existing import options, both US-made F-35 and Russian-built Su-57 have been evaluated, but neither fits our long-term strategic needs. Both platforms have been appraised but found wanting in one area or another. Delivery timelines, geopolitical realities, performance, cost, OEM dependency, and share of technology transfer are some of the reasons for this decision.

India would require 10-12 squadrons of fifth-generation aircraft in the near future. Acquiring one or two squadrons from a foreign source would just complicate our already messy supply chains.

Inordinate delays in the AMCA programme might force the government to choose one of these in the future. Thus, it’s critical that the AMCA programme delivers on time, and for this reason, the Ministry of Defence should nominate it as a mission of national importance.

The bulk of our Air Force will continue to be made up of fourth and 4.5-generation aircraft. These numbers should have been met through LCA Mk1A and LCA Mk2. However, while we wait for our domestic programmes to deliver—which could take a while—India will need to import capability.

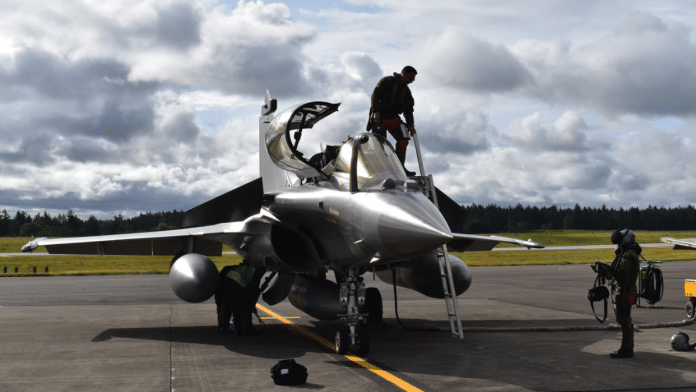

In that regard, Rafale is the only logical choice. The IAF can absorb the aircraft in large numbers and within a short period of time, as we already have the requisite infrastructure and processes in place. With two operational Rafale squadrons in the IAF and nearly 1.5 squadrons being stood up in the Navy, there is no dearth of trained manpower either.

Moreover, features in the proposed deal—technology transfer (ToT), local manufacturing (nearly 60 per cent), and offsets—would strengthen India’s domestic aerospace industry. Exposure to operating and maintaining high-end technology would also benefit the LCA Mk2 programme. Some of the techs involving sensors, avionics, and weapons could later be absorbed by our domestic programmes.

At this stage, evaluating and inducting any other imported 4.5 gen aircraft is neither cost-effective nor strategically sensible. Locally produced 4.5 gen aircraft (LCA Mk2) is yet to take its first flight.

It must be stated, even at the cost of repetition, that India would not have been forced to pay for expensive imports of a capability it can produce locally had projected timelines not slipped. In July 2015, the then Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA) director, PS Subramanyam, claimed that LCA Mk2 would take flight by 2018 and be in squadron service by 2021.

This capability would come at a significant cost, and the government would therefore have to take a long, hard look at the proposal. Insisting on technology transfer and local manufacturing could mitigate the cost to a certain extent. The option to build (or just assemble) the jet in India for other export customers could even turn this into a profitable venture.

In sum, the Rafale dilemma encapsulates India’s defence paradox: security vs self-reliance. As the Defence Acquisition Council decides the path forward, it must balance short-term security vulnerabilities with long-term self-reliance.

Group Captain Ajay Ahlawat is a retired IAF fighter pilot. He tweets @Ahlawat2012. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

This has nothing to do with socialism. China is socialist and are testing 6th gen fighters. Plenty of socialist European countries have advance aircraft and Air forces.

India’s problem is bureaucracy, slow procurement of military tech, and lack of innovation. The sab chalta hai attitude is the real problem, not some imagined socialism (and btw India has never been a true socialist country, more like protectionist with a few families and industrialist monopolizing the entire economy.

Socialism neither made India self reliant nor secure.