Dirty air has finally become an issue in Indian election manifestos, along with perennial subjects such as temple-building and farmers’ incomes. That shouldn’t be a surprise: Even politicians can’t escape air pollution, which has reduced life expectancy in areas near the capital New Delhi by more than 12 years.

To address the issue, the government earlier this year laid out a three-year subsidy program for electric vehicles valued at about $1.4 billion — about 10 times larger than a previous plan. There’s just one flaw in this impressive-looking commitment to putting more clean-energy vehicles on the roads: It’s likely to exacerbate rampant theft of electricity.

India is home to over 2 million electric two-wheelers and rickshaws — more than the number of electric cars in China. Sales of such smaller electric vehicles continue to rise. But in the absence of charging infrastructure, many of their drivers have been illegally siphoning power. Only 10 percent of the latest subsidy program is allocated for charging stations.

More than a quarter of all the power India generates is either pilfered for various purposes or lost in transmission, according to figures cited in local media as of mid-2018. The power sector loses more than $16 billion a year to theft — more than any other country in the world.

Power stolen to charge three-wheeler rickshaws costs more than $20 million a year in Delhi alone. There are 100,000 such vehicles on the capital’s roads, and only a quarter are registered. Losses for state electricity retailers rose more than 60 percent in the first nine months of the fiscal year through December.

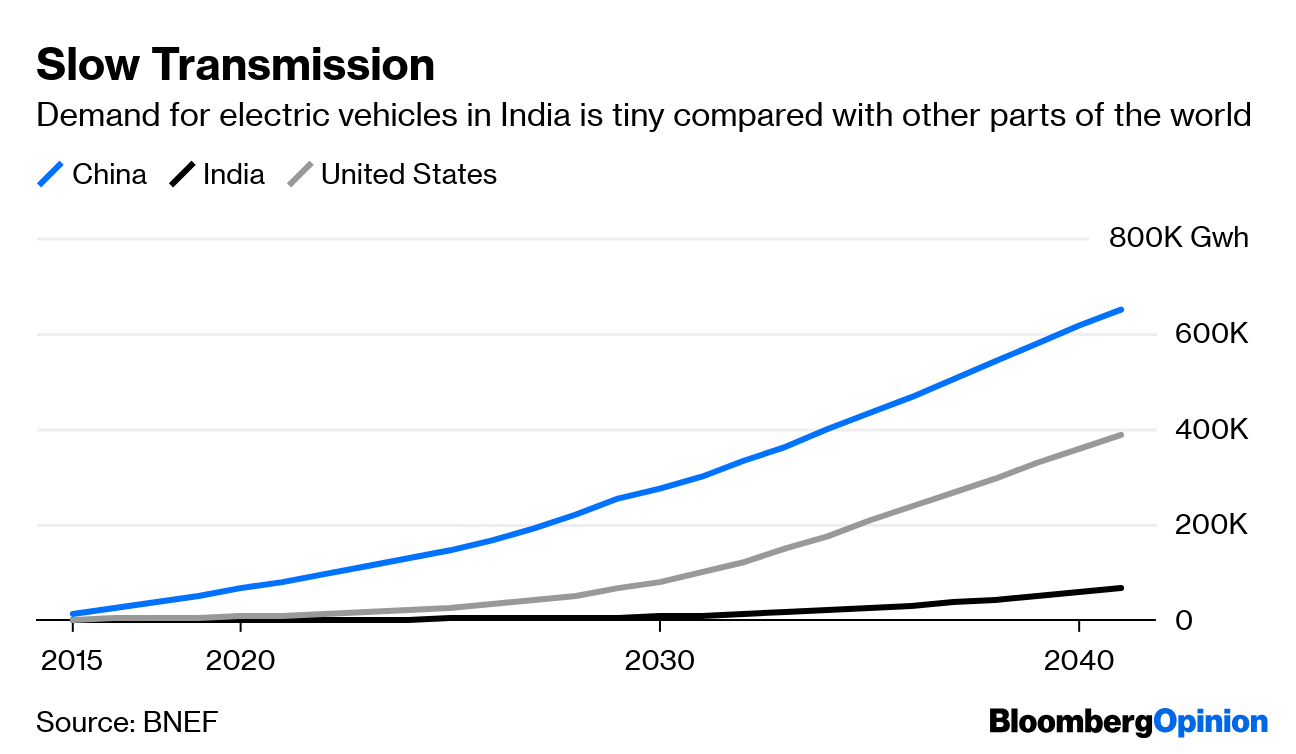

The lack of charging infrastructure has also contributed to puny demand for green passenger cars. Mahindra Electric, a unit of automaker Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd., discontinued production of its first electric car this month. Maruti Suzuki India Ltd., the country’s largest carmaker, only recently started making electric vehicles.

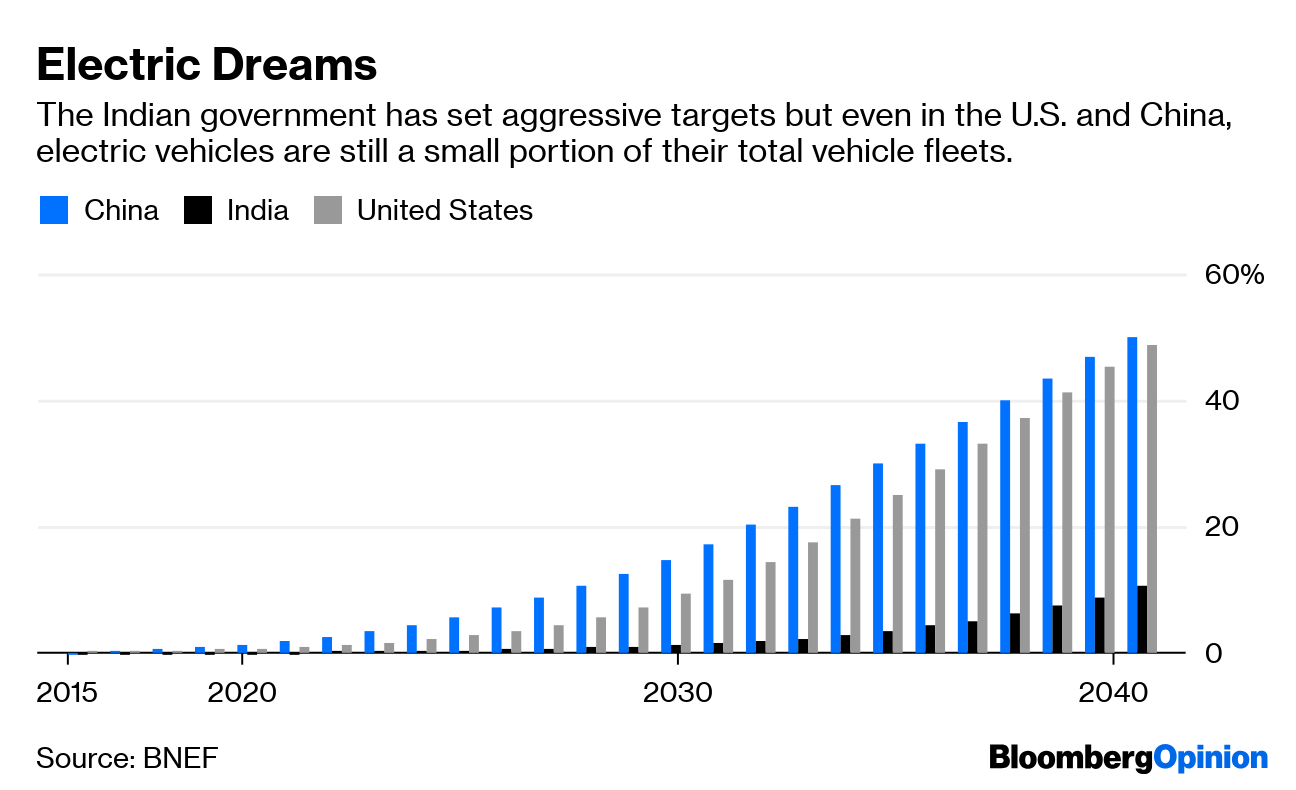

Notwithstanding, the government keeps setting itself big goals. Two years ago, India’s plan envisaged a “transformative” target of making all three-wheeler vehicles electric by 2030. Even under a business-as-usual scenario, it expected 40 percent of personal passenger cars to be battery-electric by then, from zero in 2015. In a report this month, a government planning body lauded the latest subsidy program and said it had the potential to boost penetration rates for electric-vehicle sales to 30 percent for passenger cars, 70 percent for commercial cars, 40 percent for buses and 80 percent for two- and three-wheelers by 2030.

Compare those goals with other countries’ targets and India’s start to look even more unrealistic: China, the world’s largest electric-car market, has been at it for a decade and is still targeting only 20 percent of total sales to be electric or hybrid by 2025.

Here’s the reality: Just having a green subsidy program in place is no longer enough. Sure, it’s a step in the right direction, but as China and other countries are realizing, incentives have to be targeted, adequate and suited to the country’s situation.

Assuming a moderate level of adoption, India needs about $6 billion for charging infrastructure, $4 billion in incentives and a further $7 billion to build out battery capacity, according to estimates by Goldman Sachs Group Inc. That’s a far cry from the enlarged $1.4 billion outlay, with its $140 million for charging. The latest subsidy plan focuses mainly on public transport for rickshaws, cars and buses, and on two-wheelers only for personal usage. That means most of the burden for providing charging stations still falls on the government for now — not home-chargers.

Also read: An electric vehicle revolution is underway in India—and it has nothing to do with cars

The power-generation capacity just isn’t there to support such a program. Even the highest-income neighborhoods of Delhi have to contend with electricity cuts, let alone rural and lower-income areas. A target of installing almost 3,000 charging stations in major cities and at intervals of 25 kilometers on major highways, as the plan stipulates, seems far-fetched.

Election promises are easy to make on paper. If India’s politicians want to make the air breathable again, they need to give drivers somewhere to plug in.

Anjani Trivedi is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies in Asia. She previously worked for the Wall Street Journal.