India’s Air Chief Marshal AP Singh recently described Pakistan’s claims of downing 15 Indian jets during Operation Sindoor as “Manohar Kahaniyan”.

“They couldn’t show us even a single picture. So their narrative is ‘Manohar Kahaniyan’. Let them be happy. After all, they also have to show something to their audience to save their reputation,” Singh said.

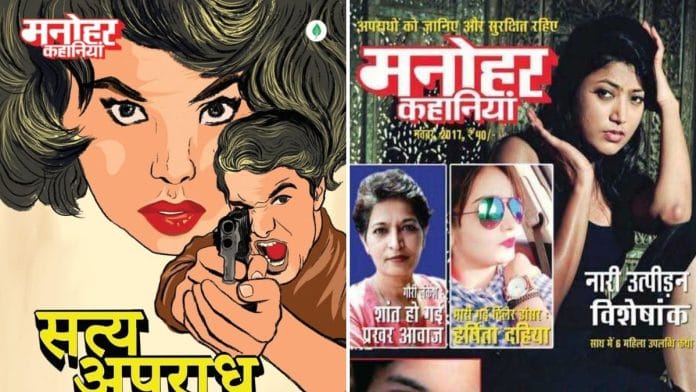

The reference to “Manohar Kahaniyan” immediately drew chuckles from those who remembered—or at least had heard of—the Hindi magazine of the same name.

Launched in 1944 by the Maya Press and acquired by the Delhi Press in 2008, the magazine enjoyed a near-universal fan base among Hindi and Urdu speakers, especially in the 1980s and 1990s. Its dramatic re-telling of real-life crime tales and social commentary gripped readers. With salacious storytelling, sensational headlines, and eye-catching images, the magazine enjoyed a wide readership. Its presence was ubiquitous: at roadside book stalls, railway stations, bus stops, as well as a large subscriber network that made the magazine a popular talking point among readers and fans of fiction magazines.

Although the magazine’s content and writing did result in it being regarded as low-brow and perhaps hampered its embrace among the social elite, it nevertheless managed to strike a balance and acquired a wide acceptance among the middle-class.

Also read: How Pakistan thinks: Army for hire, ideology of convenience

Hunger for suspense

The magazine would have crime tales with mystery and suspense. The stories were often inspired by real-life events, such as kidnappings, murders, thefts, and courtroom drama. The magazine wasn’t all entertainment; it occasionally printed stories with social messages that highlighted issues such as corruption, poverty, or injustice. It was the narrative style that made Manohar Kahaniyan unique. Short, punchy, and conversational, it was designed to be read in crowded train or bus journeys and even on work breaks.

The magazine used some stories and their headlines on the cover, and the illustrations played an important role. They were crude and striking. It was Crime Patrol before the television era—a window into the dark underbelly and the thrilling unknown of Indian society.

In 2022, the magazine also went digital, with the Delhi Press launching the website and an app.

Manohar Kahaniyan is still being sold with the same structure—popular stories written on the cover. The tales are inspired by recent crime stories such as the Raja Raghuvanshi murder case. Titles such as ‘Honeymoon Me Biwi Layi Maut (Wife Brought Death on Honeymoon)’ or ‘Instaqueen: Pati Ka Murder (Instaqueen: Murder of a Husband)’ are being sold presently. One search on Amazon, and you’ll find plenty of options to buy.

At its peak, Manohar Kahaniyan was a phenomenon. It entered so deeply into Indian society that it became a frame of reference. “Don’t make these Manohar Kahaniya”, was a popular saying.

Manohar Kahaniyan offered accessible storytelling and mixed entertainment. From crime to human folly. The magazine, like its contemporaries—Rahasya, Maya, and Satyakatha—was a product of its time: when newsprint was cheap, imagination was free, and the hunger for suspense could drive circulation numbers into the tens of thousands. In 2025, the phrase ‘Manohar Kahaniyan’ has evolved from a literal magazine to a metaphor for tall tales or exaggerated stories.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)