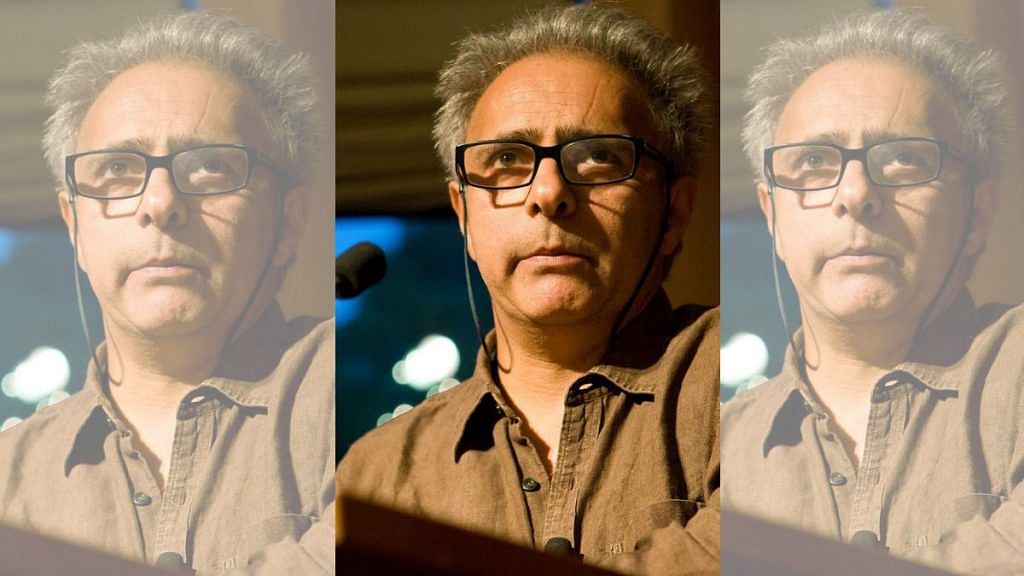

British playwright and novelist Hanif Kureishi has converted the potentially catastrophic fall that left him paralysed into a poignant and insightful ‘story’. And Twitter is his medium.

Each day, a new layer emerges as the writer takes centre stage. It is a testimony to how many multitudes a single experience can contain. Sometimes it is uncanny.

Kureishi was in Rome when he had a disastrous fall on 26 December 2022, the day after Christmas. He blacked out and woke up immobilised. Eleven days later, he tweeted: “It occurred to me then that there was no coordination between what was left of my mind and what remained of my body. I had become divorced from myself. I believed I was dying. I believed I had three breaths left.”

It was the beginning of Kureishi’s latest narrative arc. He has been confined to a hospital bed since that fateful day in December, tweeting to a loyal audience, submerging them in what was literally a life-or-death scenario. He dictates words to his son Carlo, who shares them on Twitter and in a Substack newsletter.

“A strange thing happened to me, I went to Rome with my wife for a few days and now I will never go home again. I have no home now, no centre. I am a stranger to myself. I don’t know who I am anymore. Someone new is emerging.”

At other times, he recalls mundane details. “Last night at around nine, I watched a few minutes of Glass Onion, which I enjoyed.”

Also read:

Coping with words

He delves into his past in his dispatches– talking about his motivations, stylistic fixations and how he is recalibrating his entire existence, “Seeing this phenomenon, I realised I had to start again as a person and as a writer. I had to become a comic writer, a serious writer, a writer who could integrate the maddest and most interesting elements on the same page. I began to take myself seriously.”

This is how Kureishi is using Twitter and Substack, bringing in a whirlwind of objects and emotions. From the television shows he watches, the tiles he counts on the ceiling of his hospital room, the loneliness, the love – everything finds articulation. He offers advice and shares his thoughts on writing too.

“So a four-day break, with absolutely nothing to distract you, might be a good form of shock therapy for a stuck writer. In fact, there are probably no stuck writers, just resting ones, who wait.

Kureishi’s career started 20 years ago as a pornography writer. His 1985 screenplay, My Beautiful Laundrette, “where a young gay Anglo-Pakistani man pursues the dream of opening a laundromat with his lover, a young white street tough with two-tone hair,” was a runaway success. According to Lithub, it featured “Pakistani gangsters and Thatcherite slumlords, lost college students and white supremacists from the National Front” and proved to be a turning point for both him and the film’s actor, Daniel Day-Lewis.

The writer appears to have often turned inward for his work. His 1998 novel Intimacy was also rumoured to be autobiographical. He continues to share musings on family life, discussing his parents, wife and children. “She was not mean, cruel, or uncompassionate. In fact, she could be kind. What she wanted to do was reduce the atmosphere around her to an extreme inertia where nothing was alive or could flourish,” he wrote in a Twitter post.

Also read:

The impact of radical honesty

Followers and well-wishers from around the world respond with engagement and offer encouragement to the ailing writer by sharing their own experiences. To these endearing gestures, Kureishi responds in interesting ways: “In this shitty world, all my love, Hanif,” or “In these shitty times, your loving cripple, Hanif.”

Kureishi’s vulnerability is an example of radical honesty. We are witnessing suffering in all its horror, seeing the roughest of its edges. Emerging from this unwieldy scaffolding is beauty. Kureishi can no longer hide behind characters or narratives he has constructed.

The story is unfolding—with or without him. And he has no option but to leave himself exposed. He is enslaved by it.

“The only good thing to be said for paralysis is that you don’t have to move to shit and piss,” he writes.

Essays and academic papers will be written on Kureishi’s latest work, and every word will be deconstructed. But for now, we have this: There was a Pakistani-British writer named Hanif Kureishi, and at one point, we knew him intimately.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)