A Pakistani friend recently asked me to write something explaining the concept of hybridity, which sent me back to the available literature on guided and controlled democracy. I even went looking at scholar Rebecca Schiff’s theory of concordance, in which she used Pakistan’s example to describe a method of political control and governance where the military, political class, and civil society were partners. Re-scanning the literature, however, I realised that today’s Pakistan does not fit any of the available models, as partnership portends a certain division of power that the country lacks.

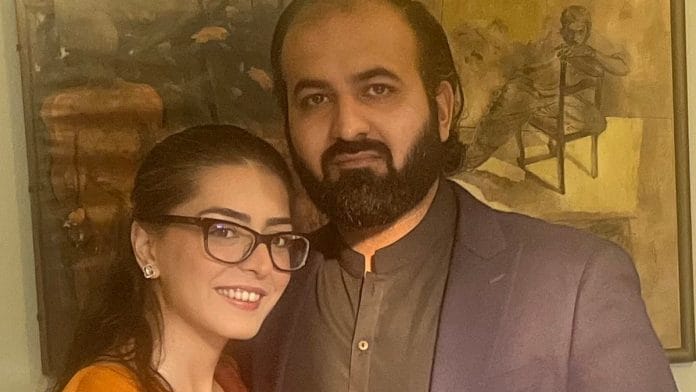

Besides many other developments, what helped define the state and regime type for me was the recent sentencing and ugly arrest of lawyers Imaan Zainab Mazari-Hazir and her husband, Hadi Ali Chattha. A session court judge in Islamabad sentenced both young lawyers to 17 years’ rigorous imprisonment for their posts on X, viewed as anti-state.

Reading the 22-page decision, it becomes clear that the poor judge may not have had much of an option. But it also makes evident that what is at play here is no civil-military partnership, but criminalised military authoritarianism, which uses its absolutely powerless political partners either to legalise the power of generals internationally or to take the blame for their sins when the need arises.

The partnership, if the term must be used, is limited to crony capitalism, or to a handful of high-ranking civilians enjoying titles without any real decision-making power.

Also Read: Asim Munir now gets a foothold in Pakistan economy. Fauji Foundation will be his front

What was the ‘crime’?

The session court decision revolves around three main allegations levelled against Mazari-Hazir and Ali.

The first was that they supported and posted in favour of ‘terrorist organisations’ such as the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) and the Baluch Yakjehti Committee (BYC), and its leader, Mahrang Baluch. Second, that they posted against the armed forces, accusing it of terrorism and forced disappearances, thus undermining public trust in state institutions. Third, that they spread false and fake information through their posts.

Interestingly, the judge, perhaps inspired by the state, drew no distinction between the BYC and the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA). While the former is a political movement asking for recourse to justice for the disappeared in Baluchistan, the latter is an insurgent organisation that the state also labels fitna-tul-Hindustan (a conspiracy or ploy of India) against Pakistan.

Mazari-Hazir and Ali’s posts on X were merely in support of the BYC and its women leaders’ right to demand the constitutional guarantee that people be tried legally rather than being abducted. At no point did either of the two lawyers justify the killing of innocent people by the BLA. Asking the state to engage in dialogue with those it considers sinners does not sound treasonous to me, or to many others.

Furthermore, the judge construed Mazari-Hazir’s post condemning the state’s policy of differentiating between “good” and “bad” Taliban as an accusation that state institutions use terrorism as a tool. The judgment is laughable, as it eagerly points out that the two accused have wrongly accused the state of terrorism, and that the four designated state sponsors for terrorism are Syria, Iran, Cuba, and North Korea.

When criticism becomes treason

What makes this case extraordinary is the manner in which the two accused were arrested, or rather violently abducted, from the premises of the court. It sent a signal that the state has little tolerance for anyone it perceives as critical, and that such voices would be slapped with treason charges.

According to the lawyer Abdul Moiz Jaferii, in an interview to the popular online media channel NayaDaur, the case has all the signs of being instigated by the establishment. A complaint initially registered by a sub-inspector of police, who noticed the posts while browsing the internet, is in itself a giveaway of who was behind it. The intent is seemingly to send a message that time is up for taking cases, or making comments, that would anger the state.

Though Jaferii claims in his interview that the case has nothing to do with Mazari-Hazir’s active role for the disappeared, especially from Baluchistan, or her voice against the blasphemy gang, the fact is that the establishment has increasingly demonstrated its intolerance for voices from Baluchistan or Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KP). It has lost the ability to differentiate between political voices and those engaging in acts of violence. The two accused were active on social media, bringing to attention the need for the state to engage in political dialogue instead of beating everyone with the same stick.

In the last few years, Mazari-Hazir’s voice had emerged as one of the few that condemned the brutal state policy applied to the people of Baluchistan and KP. Not just that, she was on the frontline, legally defending and presenting cases of the forcibly disappeared to the courts.

However, what Moiz Jaferii did not explain in his interview, for very understandable reasons, is the changing temperament of state institutions, and the increased criminality now passed off as the writ of the state.

Even ideological allies are not spared

The mood of the state has grown harsher, especially in the last three or four years, because those in control are eager to establish a hard state that brings military discipline to society. This intention evaporates civil society’s capacity to engage in any constructive partnership with the establishment, which in itself negates the very premise of Schiff’s concordance theory.

It is important to note that this hardening of attitude did not come about in a day. It started much earlier, around 2013, when the concept of hybridity was initially introduced into politics, and Nawaz Sharif took over as prime minister for the third time.

It was around the end of the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) government that the establishment started to demonstrate its lack of tolerance for dissent. The 2017 case of the four bloggers who were picked up and tortured, accompanied by other dissenting voices being forced out of the country, was the beginning of a journey that is now at an advanced stage.

This is also about a generational change in the military, where the men in charge believe that both state and society need to be transformed and developed not by just tinkering with the political class, but by taming society as well. Their inspiration is not the West, but Singapore and China, from where they have learnt that economic and political growth depends on strict social disciplining. They are ready to use greater suppression, and also to change partners within society, bringing to the fore voices eager to echo the state agenda without any addition or subtraction of their own.

This is what makes Mazari-Hazir’s case more interesting, as she is no ordinary young lawyer, but the daughter of a woman long known for her sympathy with the state’s geo-political agenda.

Dr Shireen Mazari, Imaan’s mother, is known in geo-political and strategic circles as a pro-military hawk, and for her rabid anti-India stance. She continues to hold those views.

However, sources in Islamabad told me they had witnessed signs that her relationship with the establishment was undergoing a change even when she was made Minister for Human Rights (2018-22) in the Imran Khan government. It is believed that the establishment denied her the position of foreign affairs minister that she desired, and later grew upset with her introduction of a bill in parliament in support of missing persons. She claimed in 2022 that the draft of the bill had gone missing right under her nose.

Clearly, Shireen Mazari may be a geo-political hawk, but she held different views regarding the state’s handling of domestic politics.

Also Read: Faiz Hameed conviction is a message from Munir. He won’t tolerate sympathy for Imran Khan

The fear behind the hard state

Over the years, the generals have found people, especially younger female voices, who will not only say what the GHQ wants said, but also run other errands for them. There is little room now to tolerate the fact that Dr Mazari’s daughter, Imaan Mazari-Hazir, established her own voice by being openly critical, even of her mother’s views and policies, particularly on social media. As Dr Mazari herself graciously admitted, her daughter often held opposing views and proved her mother wrong on many counts.

Unlike some who, with mala fide intent are digging up my old tweets, I stand by what I have said & admit to mistakes I made. @ImaanZHazir & myself have had public diff of opinions & she has proven me wrong on many counts! We never had PECA or autocratic rule at home! So deal with…

— Shireen Mazari (@ShireenMazari1) January 26, 2026

This is despite the fact that she grew up in a household where her mother was visibly sympathetic to the armed forces. One is also reminded of accounts of a dialogue between Imaan and General (retd) Qamar Javed Bajwa, who, while serving as army chief, once told the young girl to be more sympathetic, as the army is not so bad. Such indulgence is no longer on offer.

The establishment under Army chief Asim Munir, with his hard state mindset, lashes out not only at ordinary people who don’t toe his line, but even at those whose families have traditionally been sympathetic towards the military. In fact, the anger may be greater at watching Shireen Mazari unable to discipline her daughter.

Those in uniform definitely hate Mazari’s daughter, especially at this juncture, for her ability to draw attention toward a regime that would rather be free of scrutiny. As some journalists I spoke with pointed out, the generals resent Imaan Mazari-Hazir even more after the Norwegian ambassador went to court for the hearing, for which he was issued a formal diplomatic demarche.

This growing anger, and the handling of dissent in KP and Baluchistan, or cases like Mazari-Hazir’s, is symptomatic of the GHQ’s changing mood, tone, and tenor—a willingness to turn more brutal.

Moments like this remind me of the Pakistan where I lived not too long ago, writing and saying things for which I would certainly get brutally punished and silenced today.

Yet this increased criminalised authoritarianism also indicates the growing lack of confidence of those who run the state. It denotes their nervousness even of voices and shadows that remind them of how temporary their power is, or that changing Pakistan, and making it functional, is a herculean task that will not be achieved through suppression and the death of politics and society.

Ayesha Siddiqa is a senior fellow at the Department of War Studies at King’s College, London. She tweets @iamthedrifter. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Pakistan has gone through several “institutionalised criminal regimes”. Nothing changed. Nothing will.