In all the centuries that the Olympic Games have been played—whether between the city-states of ancient Greece or in the dazzling arenas of 2024 Paris—they have aspired to be something beyond the political. For evanescent seconds, as athletes push the limits of human achievement, the boundaries of our nations blur. But sport wasn’t always this transcendental, nor was it always for humans. For most of history, sports were played for entertainment—and in medieval India, humans and animals were both athletes, sometimes competing against each other. The results could be thrilling, grisly—and often wacky.

The elephant-arena

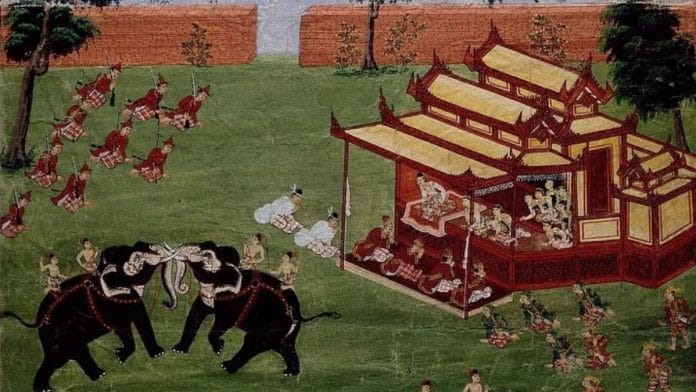

It’s not going to be possible to explore all of these sports in a single article, so here are some of the most interesting (and dangerous) ones. Let’s start with elephants: Worshipped, used in war and construction, and occasionally as athletes in the thrilling sport of elephant racing. Elephant racing was described in detail by the Deccan ruler Someshvara III in his Manasollasa, a 12th-century court manual.

Medieval elephant arenas were 600 feet long and 360 feet wide, with grounds carefully cleaned to remove stones, thorns, and other prickly objects. Arenas were levelled so that the east was slightly raised. On this end, a viewing pavilion was erected, fortified with a ditch outside, painted and decorated inside.

Three racers were lined up in front of three male elephants, and the angered animals would chase them along three separate tracks. The humans didn’t race each other — their competitor was the elephant they were paired with. The elephant’s trunk might contain water, or carry a gourd; if it threw either away, the human won. If the human managed to mark the elephant’s tusks with powder, he won. The human could also win by racing the elephant across the entire 600-foot track. And of course, if the human was killed by the elephant, they definitely lost.

In contrast to today, medieval runners weren’t professionals. The Manasollasa says that thieves were sometimes put on the elephant track, with their hands tied. If they won the race, they were released, and if they died, they were “liberated from sin”. Others raced the elephant for rewards, to escape humiliation, or to humble a rival. Poor or desperate people were subjected to danger for elite entertainment, but sometimes things could go very wrong. If an elephant was in musth, it might forget about its human racer and instead attack the king’s guards and spectators, even reaching into the fortified ditch to slaughter people. All things considered, not an ideal Olympic sport.

Also read: How did taxes work in medieval India? Chola, Mughal subjects struggled like today’s middle-class

Wrestling matches, human and animal

Interestingly, the Manasollasa also describes a game similar to polo, perhaps evolving from the Deccan horse trade with West and Central Asia. In a square arena of 400 x 400 feet, two teams of eight tried to knock a ball through goalposts on opposite sides. It was a game of considerable skill. The ball was passed from one player to another by catching it in the polo stick, rather than simply hitting it. Since horses were expensive, imported animals, polo players tended to be aristocrats—they practised polo because it paid off on the battlefield.

So, if medieval runners and polo players weren’t professional athletes, who were? Wrestlers. (As Vinesh Phogat’s performance this year shows, despite heartbreaks, it’s a sport in which India continues to excel). Medieval kings maintained large numbers of wrestlers, usually between 20–32 years old, and provided them with a special diet of legumes, meat, and milk sweets. In Nation At Play: A History of Sport in India, Ronojoy Sen describes their regimen. Wrestlers were prohibited from speaking with women and exercised with heavy clubs and sacks of sand.

They strengthened their core by lifting themselves perpendicular to a pillar. They were frequently used in royal entertainments, and their bouts could be quite violent. Sen, drawing on the testimony of Portuguese travellers, writes that by the 1500s, South Indian kings maintained perhaps hundreds of wrestlers. They used knuckle-dusters to fight each other and received gifts of silk and gold. By the 1800s, they even employed bladed knuckle-dusters called vajra-mushti, sometimes even kicking and biting, but stopping bouts once blood was drawn.

Wrestling was quite an art form in medieval India. It wasn’t just men but even elephants, rams, roosters, buffaloes, and even quails that were brought to wrestle in the palace. Though Someshvara doesn’t mention it, all these matches must have been accompanied by lively betting. Roosters were even armed with daggers on their feet. If a rooster was victorious, its owners got to sit on the backs of the defeated rooster’s owners, singing mocking songs. And if a rooster won six matches in a row, it was garlanded, dressed up, given gold necklaces, and even paraded through town on elephant back.

Also read: Yoga, Sanskrit inspired Sufi epics—Chakras became ‘mystical stations’, gods turned ‘angels’

The hunt

Wrestling pitted human against human and animal against animal. Elephant races pitted human against animal—to the animal’s favour. But the royal hunt completely flipped the script: It established in no uncertain terms that humans ruled animals, proudly and brutally.

The Manasollasa describes 31 varieties of hunting to be conducted in royal reserves patrolled by buffalo-riding sentries. The sentries were to kill any dangerous animals that wandered in, like tigers — the royal reserve was for the king alone to display his prowess.

Deer were hunted in devious, inventive ways. Trained deer were used to lull wild herds into complacence before they were ambushed by the king’s party. The hunters might be camouflaged in green, carry tree branches or conceal themselves behind bullocks. Sometimes wild animals were partially tamed through regular feeding and hunted once they lost their fear of humans. Drum-beaters were used to herd animals toward nets and pits, where they were killed. Deer were tracked during storms, their hiding places were found during the monsoons, and they were chased down by dogs, horse riders, and trained cheetahs.

Unlike in most of my columns, this brief exploration of medieval sports doesn’t really have a moral or takeaway. The medieval world is sometimes familiar, sometimes funny, sometimes terrifyingly alien. All in all, the contemporary Olympic Games are a much more humane way for us to indulge our instinct to compete, push the boundaries, and be better.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval’ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)