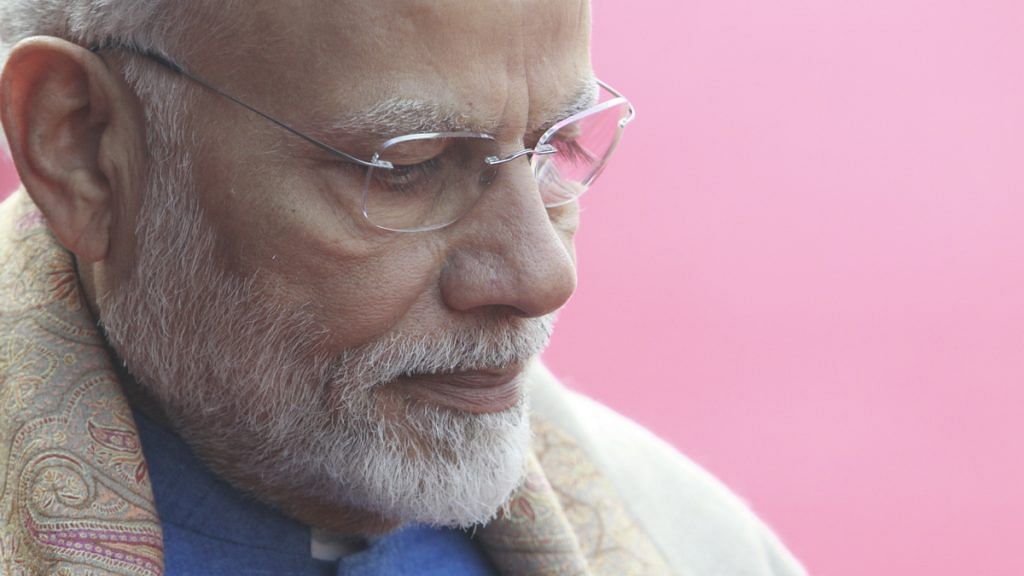

Prime Minister Narendra Modi captured the change in Indian politics with a simple turn of phrase. In 2014, Modi came to power with the slogan ‘sabka saath, sabka vikas’ — supporting everyone, everyone’s development. After bettering the BJP’s impressive 2014 performance in the 2019 Lok Sabha election, Modi quipped, ‘sabka saath, sabka vikas, aur ab sabka vishwas’ — supporting everyone, everyone’s development, and now everyone’s trust.

The explicit inclusion of vishwas (trust/belief) in the slogan is telling. It is an understanding of politics that is based on the personal popularity of Modi, and the trust that voters have placed in him. One can juxtapose this trust-based conception of politics against one of ‘democratic accountability,’ wherein voters place well-defined demands on the elected representative and support him/ her based on the fulfilment of these demands. I call this accountability-based model the politics of vikas (development) because it is common to claim that politicians and leaders are judged on economic delivery. In contrast to this view of accountability-based voter behaviour in India, I wish to develop a model of vishwas, and how it structures politics – which I believe is helpful in understanding the current moment in Indian politics.

The overturning of historical empirical patterns on elections is straightforwardly associated with the centralisation of political power in the Modi government. This centralisation, and the extraordinary level of support for Narendra Modi and the BJP, is a natural outcome of the politics of vishwas. This is a form of personal politics in which voters prefer to centralise political power in a strong leader, and trust the leader to make good decisions for the polity – in contrast to the standard models of democratic accountability and issue-based politics, which place power in the hands of citizenry.

In order to develop the argument, I argue that two factors lead to the BJP using the politics of vishwas to dominate Indian politics. First, like much of the world, there is an increasingly strong axis of conflict between those who believe in a unitary (Hindu) national identity for India and those who view India in ‘multicultural’ terms. This obliges supporters of Hindu nationalism to support political centralisation to stymie federalism, which would require negotiation across regional, linguistic, caste, and religious identities. Second, the BJP’s control of media and communication with the voter, in tandem with a strong party machinery, give the party structural advantages in mobilising voters around the messages of Modi.

Also read: PM Narendra Modi shares document on ‘vikas yatra’ during his govt’s second term in office

Hindu nationalism and centralisation of power

As Przeworski et al. has shown, poorer countries are highly susceptible to democratic breakdown. India was the democracy that was never supposed to survive.

But India has long been an outlier; it is by far the poorest of longstanding democracies around the world. In perhaps the closest investigation of why India remains a democracy, Alfred Stepan, Linz, and Yadav argued that the persistence of India’s democracy results from the very idea of India – a federal structure that respects and allows compromise between multiple ethnic and religious identities – which prevents the centralisation of power that constitutes democratic breakdown. The compromises between regional and national identities, across religions and castes, enshrined in federalism are often seen as necessary for the persistence of Indian democracy.

This is a contested position, and India’s federal structure has consistently been under attack from those aligned with Hindu nationalism. Furthermore, this democratic procedure of generating agreement among various stakeholders and competing interests can be frustratingly slow and require painful compromises, especially with the plethora of caste, religious, linguistic and ethnic interests in India. Indeed, Samuel Huntington (2011) presciently understood that, after the end of the Cold War, economic or ideological conflict would eventually give way to ‘cultural’ conflict across the world – that a single, national identity would come into conflict with ideas of ‘multiculturalism.’ His work is troubling due to its open racism, but it presages, for instance, the rise of Donald Trump and Brexit.

Huntington’s arguments are also applicable to the rise of Hindi-speaking Hindu nationalism in India. The World Values Survey (WVS), which has collected data across the world in five-year waves since the 1980s, documents the recent rise in religiosity in India.

Figure 1. Percentage of respondents claiming importance of religion over time

In the West, with consolidated nation-states around a particular ethnic or religious identity, cultural conflict typically takes the form of aggressive anti-immigration policies. In India, this cultural conflict has the taken the form of defining a Hindi-speaking Hindu nationalist identity at the expense of other regional, linguistic, or religious identities within its own borders. This obliges those supporting this form of nationalism to centralise power in a leader who can effectively stifle opposition from these competing identities. This is also borne out by the data.

Figure 2. Percentage supporting rule by a strong leader

The empirical desire for political centralisation also speaks to the increasing relevance of the politics of vishwas, the explicit linking of an individual’s personal character and decision-making with defending a singular national identity for India.

Also read: Disappointment, disastrous management, diabolical pain: Congress on first year of Modi 2.0

Building around Modi

The popularity of a leader is not created in a vacuum. It requires a significant amount of image control. Concurrent with the rise of Right-wing populism across the world in the recent years, stark changes in the media environment, particularly in the form of social media like Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp, generated a far more decentralised media environment. While this means that the citizen has more choice, it also implies that citizens may choose media that aligns more closely with underlying biases, irrespective of the truth content. Thus, an individual with anti-Muslim beliefs can choose only to consume media from sources that explicitly espouse anti-Muslim positions. This is often referred to as the ‘echo chamber’ problem.

This allows political actors to craft narratives and even promulgate ‘fake news’ among its supporters – core to the function of the politics of vishwas. The extraordinary penetration of Narendra Modi into all means of communication – whether it is television, print media, social media, or WhatsApp – is an important factor. In order for the popularity of Narendra Modi to translate into electoral support, the BJP needs to consistently find creative ways of communicating with the voter.

Of course, none of this would be possible without significant financial resources. The BJP receives nearly all of the electoral financing in the system. After the controversial ‘electoral bond’ system was implemented to allow for anonymous political donations and to remove certain limits on corporate donations, one can only calculate to whom donations are given, not the source. The data from fiscal year 2017–2018 provided from Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) shows that the BJP received Rs 210 crore out of the total of Rs 222 crore in electoral bond financing, a whopping 95 per cent.

Also read: Modi faces no political costs for suffering he causes. He’s just like Iran’s Ali Khamenei

Vikas vs. vishwas: an analysis of voter turnout

The politics of vishwas suggests that the greater the turnout change in the constituency, the greater the electoral chances for the BJP. The politics of vikas suggests the opposite – the greater the turnout change in the constituency, the worse it is for BJP’s electoral prospects.

Using data provided by the Trivedi Centre for Political Data (TCPD) at Ashoka University, I consider the turnout changes in three national elections, as compared to the previous election – 1999 (vs. 1998), 2004 (vs. 1999) and 2014 (vs. 2009) – and its impact on the probability of the BJP winning.

Figure 3. BJP performance vs. turnout change

There is a discernible negative relationship between turnout change and the probability of the BJP winning in 1999 and 2004, when the BJP was the incumbent. And there is noticeable positive relationship between turnout change and BJP’s strike rate in 2014, when the BJP was in the opposition. The general trend, thus, provides evidence for the politics of vikas.

In 2014, an increase in turnout was strongly associated with BJP victory. In constituencies where turnout was less than 5 percentage points, the BJP had only a 24 per cent strike rate, but when the turnout increase was more than 5 percentage points, the BJP had an 81 per cent strike rate. The 2014 national election saw, at the time, the highest ever turnout in Indian history at 66 per cent. The strong turnout for the BJP in 2014 is consistent with the narratives of strong anti-incumbency for then-ruling Congress as well as the strength of BJP’s voter mobilisation (i.e. consistent with both the politics of vikas and vishwas). The 2019 national election, with the BJP as an incumbent, affords us the opportunity to disentangle the vikas and vishwas narratives.

The 2019 national election saw very high voter turnout once again. At 67 per cent, it was the highest turnout ever recorded in Indian history.

Figure 4. BJP performance vs. turnout change in 2019

Noticeably, turnout increase is pro-incumbent in this election, not anti-incumbent as it has been in previous elections. This provides some evidence that voters were motivated by the politics of vishwas (and not the politics of vikas) in the 2019 election. This also is strongly suggestive of the fact that the very structure of electoral politics has changed as compared to the recent past.

In the run-up to the 2019 election, there was a strong narrative around a disaffected rural voter that would punish the incumbent BJP. As we now know, the BJP did not suffer major losses in rural India

The most rural parts of the country are in its ‘Hindi heartland,’ a region consisting of about 40 per cent of India’s population, which has for some time constituted a stronghold for the BJP. Unlike the party fragmentation that has occurred through the rise of regional parties elsewhere, this is a region largely characterised by two party contests between the BJP and the Congress. If the BJP were to falter in rural areas, the Congress would have been the direct beneficiary – especially as Congress is associated with higher crop prices and the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS).

Figure 5. BJP margin of victory against Congress by rural area in 2019

Figure 6. Turnout change in BJP-Congress contests by rural area in 2019

This empirical relationship provides strongly confirmatory evidence in adjudicating between the two narratives of turnout. Were rural citizens more likely to turnout because they were frustrated with economic distress? Or, were they more likely to turnout because rural areas are precisely where BJP’s strong party organisation is effective? As we now know, the BJP increased its vote share and turnout most significantly in rural areas – providing suggestive evidence that turnout in rural areas was more a function of vishwas than vikas.

Also read: A chaiwala is PM, but it’s the cartel of power elites that calls the shots in India

Conclusion

Just as the 2019 national election drew to a close, Prime Minister Modi went to meditate in a cave near the holy Kedarnath shrine. As he emerged from the cave on voting day, wearing a saffron robe, Modi was thronged by the media. He spoke deliberately, like a sage. While lesser mortals were busy doing the business of politics – getting people to the polls, checking for campaign violations from the opposition, making sure the voting process was fair – Modi seemed above it all. In contrast to the dirty, corrupt world of politics, here was a man who projected purity and clarity. As voters went to the polls, they didn’t think about Modi’s promises or his performance, they thought about who he is.

Charisma and religion have long been a part of Indian politics, but never had we quite seen something like this on such a large scale. It required careful choreography, a compliant media, a party organisation that could mobilise voters around such an image, and a man in whom voters could place their trust. This represented the culmination of the politics of vishwas. People would vote for Modi (and the rest of the BJP) because of their vishwas in him.

In politics, it’s not only a matter of which party wins, it’s also a matter of how the party wins. How a party wins has implications for the mandate given to the winning party and structures the incentives of newly elected leaders. The politics of vishwas is a form of politics that engenders centralisation of power. Thus, not only because the BJP had a thumping victory, but also because of how the BJP won, an extraordinary amount of power has been arrayed to the Prime Minister. The sort of popular authority given to Modi means that he no longer has to negotiate with other political actors, or even many of India’s institutions, to execute his political will.

But because this a politics predicated upon the unassailable character of Modi who is capable of policy execution, it also obliges him to regularly demonstrate his power and to keep his political rivals at bay. In the intervening months since his election, the Prime Minister has been active. He sanctioned an unprecedented crackdown in the erstwhile Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir that has virtually snapped all forms of communication from mobile phone to internet to landline and led to the ‘preventive detention’ of all major political leaders in Kashmir. It has also led to what many have called the intimidation of those critical of the Modi government – like Congress politician P. Chidambaram and civil rights attorney Indira Jaising. Those aligned with the government have also used aggressive police and state tactics to arrest, detain, and at times cause physical harm to those protesting the government’s policies.

There are real fears that these constitute the first steps in democratic breakdown. Indeed, the centralisation of power, and the inability of political opposition to compete on equal footing, if often seen as a sign of democratic breakdown (Dahl 1972). Our typical understanding of democratic politics is predicated upon how voters should behave during elections, namely with some notion of political accountability. As the politics of vishwas gains hold, we are forced to grapple with what this means for the state of Indian politics and Indian democracy.

The author is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Ashoka University and Visiting Senior Fellow at the Centre for Policy Research. Views are personal.

This is an edited excerpt from the author’s article The politics of vishwas: political mobilization in the 2019 national election, which was first published in the Contemporary South Asia journal.