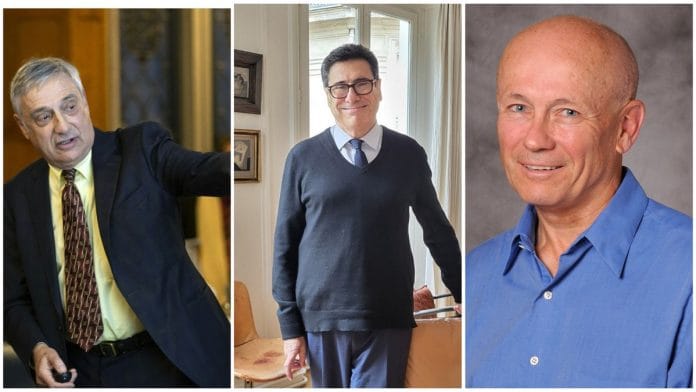

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences was awarded to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt for their groundbreaking work on innovation-driven economic growth. Their research offers a critical insight: sustained prosperity is not a natural condition but a dynamic process, propelled by continuous innovation and the creative destruction of obsolete technologies and institutions.

For India, standing at the cusp of its own economic transformation, the work of these laureates is more than theory; it serves as a roadmap for cultivating a dynamic, self-renewing economy.

Historically, India’s growth has been significantly driven by demographic advantages and incremental technological adoption. The challenge ahead lies in creating an ecosystem where innovation is endogenous, continuous, and socially endorsed. And where creative destruction is embraced rather than feared.

Also Read: Why the Nobel Prize continues to elude India

In with the new, out with the old

Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt’s research rigorously formalised the concept of creative destruction within a comprehensive model of endogenous growth. They demonstrated that economic growth is not merely a consequence of accumulating capital or labour, but emerges from a dynamic process in which new technologies replace older ones. Within this framework, incumbents are perpetually challenged, compelled to innovate or risk obsolescence.

This has significant implications for policy. Growth is not automatic, and protecting established firms or monopolies from competition slows innovation. Instead, policymakers must cultivate an environment that rewards entrepreneurship, risk-taking, and experimentation. The competitive nature of capitalism is not a flaw, but its fundamental characteristic. When competition is stifled, economies stagnate.

Joel Mokyr augments this theoretical framework with historical insight. His research, particularly his book A Culture of Growth, examines why modern economic growth first emerged in Europe rather than other regions.

Mokyr emphasises that technological advancement is not solely a product of mechanical knowledge but is also influenced by culture, institutions, and a societal willingness to experiment, accept failure, and exchange ideas freely. He illustrates that periods of rapid innovation coincided with societies that valued intellectual inquiry and open communication — what he terms the “Republic of Letters”.

The lesson for India is evident: while technical proficiency is necessary, it is insufficient without the social infrastructure of curiosity, openness, and critical discourse.

Schumpeter meets Shiva

The contributions of the Nobel laureates are profoundly aligned with the ideas of Joseph Schumpeter, who famously described capitalism as an evolutionary system in which economic life is continuously reshaped by innovation.

In his view, “creative destruction” is not merely a byproduct but the driving force of progress: new industries and technologies replace the old, generating wealth, displacing labour, and continually remaking society.

There’s a notable parallel to this in Indian philosophy. Lord Shiva symbolises destruction as a necessary precursor to regeneration, as also pointed out in a Business Standard article by Vimal Kumar.

In the cosmic dance of Tandava, endings create the conditions for new beginnings; destruction becomes creative, and chaos becomes fertile. Similarly, in modern economies, outdated firms, obsolete technologies, and inefficient institutions must be dismantled to accommodate the new.

However, India’s regulatory and political frameworks often resist this cycle, opting instead to protect legacy firms and shield workers from disruption. While the reluctance is understandable, it slows down the pace of innovation and diminishes the economy’s adaptive capacity.

Why this matters for India

Economic growth is no longer merely a matter of expanding manufacturing facilities or increasing IT exports; it now necessitates fostering continuous innovation capable of competing on a global scale. However, India faces structural challenges. While startups are emerging at a remarkable pace, many operate in sectors shielded from full competition. Large established firms, often protected by regulatory measures or political influence, experience minimal pressure to innovate.

The cultural aspect highlighted by Mokyr is equally relevant. Indian institutions, including universities and public research centres, have traditionally prioritised rote learning over experimental approaches. Although the country produces a substantial number of engineers and scientists, factors such as risk aversion, bureaucratic inertia, and fragmented knowledge networks hinder transformative innovation.

Addressing these issues demands both policy and cultural change. We need policies that incentivise experimentation, facilitate the entry and exit of firms, and reduce regulatory barriers. We must also create a cultural climate that encourages curiosity, debate, and the acceptance of failure as an integral component of growth.

Creative destruction, with humane management

India’s strategic response to these insights should be comprehensive. Innovation must be integrated not only within prominent sectors such as artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and space exploration, but also throughout the wider economy, encompassing small-scale manufacturing and regional services.

To foster entrepreneurial dynamism, it is essential to reduce entry barriers, streamline compliance processes, and enhance access to financial resources. The concept of creative destruction should be embraced as a catalyst for productivity, rather than resisted due to concerns about disruption.

Equally important is the humane management of transitional phases. As businesses fail and technologies become obsolete, workers face displacement. India must prioritise investment in reskilling initiatives, portable social insurance, and labour mobility across sectors and states. Without these measures, the process of creative destruction may provoke social and political resistance, thereby hindering the very innovation it aims to promote.

Public investment in research and open science is also vital. Mokyr’s historical analysis indicates that societies investing in knowledge creation and free intellectual exchange have enjoyed long-term technological advantages. India’s research institutions, including the IITs and CSIR laboratories, must be strengthened, interconnected, and opened to collaboration with private innovators to accelerate the cumulative process of technological advancement.

Finally, India can capitalise on its federal structure to experiment with innovation policies at the state level. States such as Karnataka and Telangana have emerged as centres of technological innovation, illustrating the benefits of decentralised, competitive policy experimentation. Replicating such successes across the country can foster a dynamic, multi-polar ecosystem of innovation.

Also Read: Inflation no longer dictated by just monsoon, repo rate. Why India needs a trade exposure index

Guarding against stagnation

The Nobel committee’s press release also carried a cautionary note: economic stagnation is historically the norm rather than the exception. Growth must be continuously revitalised; otherwise, societies risk slipping into complacency.

India’s challenge is not solely to achieve growth but to ensure that such growth remains innovative, inclusive, and self-sustaining. Protecting established entities, resisting change, or prioritising short-term political gains over long-term competitiveness can all lead to stagnation traps. A vigilant commitment to the cycle of creative destruction is essential to avoid these pitfalls.

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences is more than just a celebration of intellectual accomplishment; it serves as a call to action. It reminds us of the notion that economic growth is not automatic and that innovation requires cultivation, protection, and the capacity to disrupt. India has the requisite talent, capital, and demographic advantages to lead in this domain, yet it must harmonise its policies, institutions, and cultural frameworks with the principles articulated by Mokyr, Aghion, and Howitt.

If Schumpeter met Shiva, they would likely agree on a simple truth: destruction is not the enemy of prosperity, but its prerequisite.

Ultimately, innovation extends beyond technology; it is intrinsically linked to the society that produces it. India has the opportunity to build a society where innovation is continuous, inclusive, and deeply rooted in its cultural fabric — one that confidently navigates the interplay between creation and destruction.

Bidisha Bhattacharya is an Associate Fellow, Chintan Research Foundation. She tweets @Bidishabh. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)