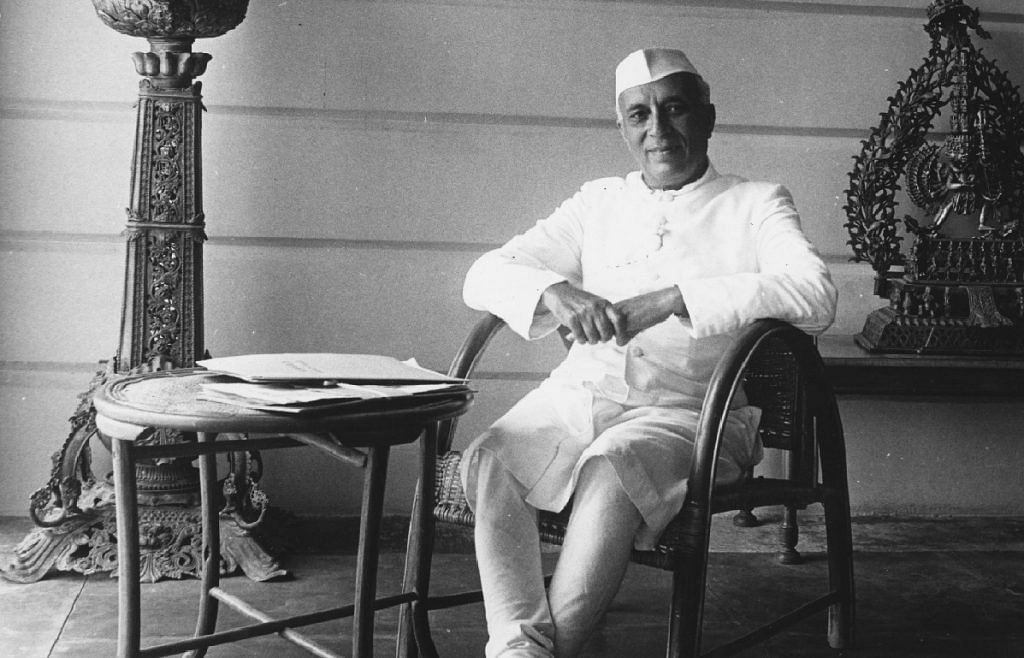

The birth of the Indian space programme had much to do with the closeness between Nehru, Sarabhai and Bhabha and Nehru’s belief in science.

In April 1954, Jawaharlal Nehru inaugurated the new building of the Physical Research Laboratory (PRL) in Ahmedabad. The laboratory had been started in a modest way in 1947 by Vikram Sarabhai. Nehru knew the Sarabhais, the leading mill owners of the city, well. Both shared a closeness with Mahatma Gandhi; both Nehru his father, Motilal, had occasionally stayed in the palatial Sarabhai house in Shahibaug.

Apart from personal considerations, one imagines Nehru would have had reason to be drawn to his young host, a physicist returned from Cambridge to practice science in India. A fervent believer in the merits of science, Nehru had already propelled the establishment of national laboratories, institutes of technology, and the setting up of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), the last-mentioned headed by another Cambridge-educated scientist, Homi Bhabha, who was a personal favourite.

Bhabha and Sarabhai were friends. Both had spent the turbulent years of World War II at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore, where Sarabhai commenced his exploration of cosmic rays and properties of the upper atmosphere.

Across the world, scientists were preoccupied with space and the emerging possibility of using satellites to study space evident in events such as the International Geophysical Year (1957), and the setting up of agencies like the Committee for Space Research (COSPAR), established by the International Council of Scientific Unions.

Bhabha and his proximity to the Prime Minister were key factors in propelling India’s space ambitions. In August 1961, at his urging, the Union government identified an area known as ‘space research and the peaceful uses of outer space’, and placed it within the jurisdiction of the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE).

PRL was recognised as the ‘appropriate centre’ for research and development in space sciences, and Sarabhai was co-opted into the board of the AEC. In February 1962, the DAE created the Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR) under Sarabhai’s chairmanship to oversee all aspects of space research in the country.

India’s desire to initiate a space programme was perceived as an audacious move by the developed world, but it was in keeping with the Nehruvian faith in technology. As early as 1938, Nehru said: “The economy based on the latest technical achievements of the day must necessarily be the dominating one. If technology demands the big machine, as it does today in a large measure, then the big machine, with all its implications and consequences, must be accepted.”

If the idea of a space programme was considered audacious; its origins, centred on individuals and friendship, seem equally, if not more, audacious. Nehru has often been criticised for partiality and over-indulgence towards Bhabha. At the same time, it is hard to dissociate the origins of the space programme from the inspirational environment of the Nehruvian era, and Nehru’s ability to fire well-educated and well-placed people with a zeal for nation-building.

“Let us get on with work, hard work”, he said in 1948. “In India, there is no lack of human beings, capable, intelligent, and hard-working. We have to use these resources, this man power in India.”

The stated purpose of the atomic energy programme was to produce power, but a wide awareness existed about the possibility that it could be used covertly to make a bomb. Space research offered a similar dual-purpose potential, but the Indian space programme came to be known for its commitment to peaceful uses rare in a world where space programmes were commonly allied to military goals.

Indeed, as Sarabhai moved away from pure scientific research to articulate the range of applications expected from a space programme by the late 1960s, a list which included communications, remote sensing, weather forecasting and so on, he seemed to echo Nehru’s ideas of applying technology to development.

In his biography of Nehru, S. Gopal describes Nehru’s eagerness “to emphasise the indispensability of scientific development” (which the British had done little to promote), “and to draw attention to the immense possibilities which the proper use of technology would open up”.

Planning then, as Gopal asserts, was to some extent ‘science in action’.

(The author is visiting faculty, Centre for Contemporary Studies, Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru.)