The gossip in the newspapers regarding the first President of India began sometime in April 1949 itself. Both Rajagopalachari and Rajendra Prasad held almost parallel positions.

By September 1949 the Constituent Assembly’s work was almost over and the new Constitution was to come in force on 26 January 1950. The gossip in the newspapers regarding the first President of India began sometime in April 1949 itself.

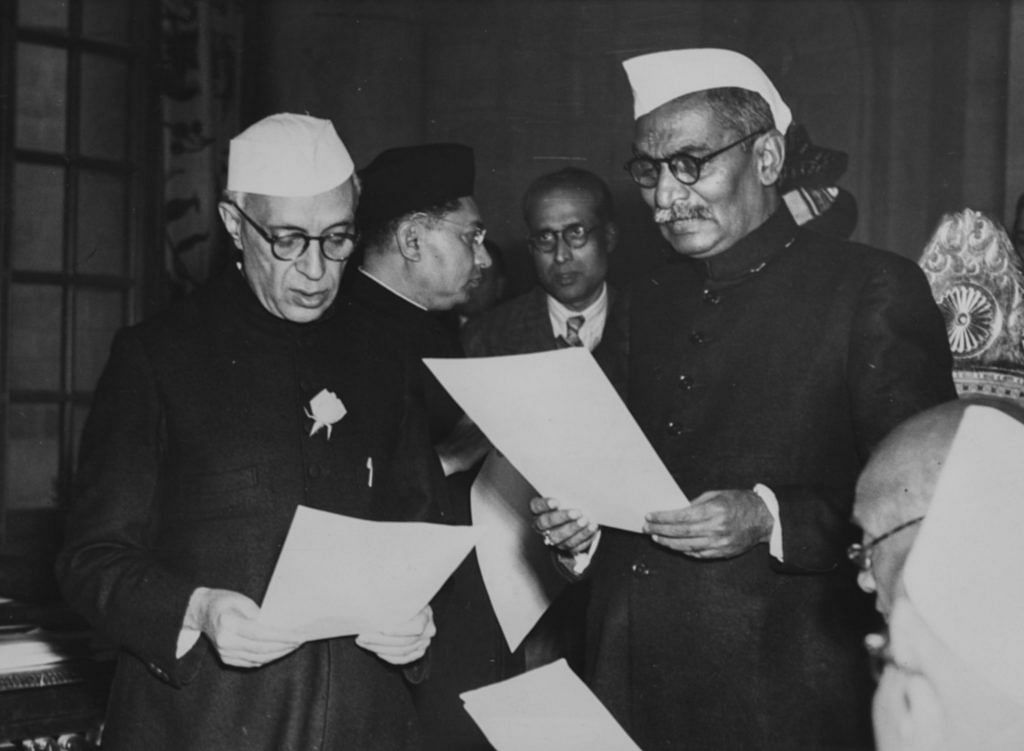

Both Rajagopalachari and Rajendra Prasad held almost parallel positions—the former was Governor General, the latter was the President of the Constituent Assembly, which was to elect the first President of India.

In order to discourage speculations and gossip, Prasad issued the following statement on June 10, 1949:

“There is and there can be no question of any rivalry between Rajaji and myself for any post of honour. I would, therefore, warn the public not to be misled by any propaganda of this nature and request all not to indulge in it.”

This closed the issue for some time. However, Nehru had decided in favour of Rajaji, without consulting with Congress leaders. In order to pre-empt Prasad’s chances, Nehru wrote to him on 10 September 1949:

“As the session of CA [Constituent Assembly] is drawing to a close, we shall soon have to decide about the manner of election of the President of the Republic…I have discussed this matter with Vallabhbhai and we felt that…Rajaji might continue as President…It was for this reason that Vallabhbhai and I felt that Rajaji’s name should be put forward by you for unanimous election…”

Prasad wrote a very long reply, copying it to Patel on 11 September 1949. He was very hurt, and expressed his surprise that Patel and Nehru were dictating to him:

“Please excuse the length of this letter and the feeling that I cannot help entertaining that I deserved a more decent exit, particularly when I did not want an entry…”

Patel was greatly surprised at Nehru’s dragging his name into the matter without consulting him on the issue. Nehru replied on 11 September, 1949 with a copy to Patel:

“Vallabhbhai, in any event, has nothing to do with what I wrote to you. I wrote entirely at my instance without any reference to Vallabhbhai or consultation with him…Vallabhbhai knows nothing about my writing to you. I am deeply sorry that I should have hurt you in any way or made you feel that I have been lacking in respect or consideration for you.”

Nehru wanted Rajaji because he had already learnt the niceties and protocol of receiving large diplomatic delegations:

“It had taken sometime for Rajaji to gradually adopt himself to these niceties of protocol. To have a change meant going through those processes again. For these reasons I thought Rajaji might as well continue.”

Both Nehru and Prasad kept copying Patel, who wrote on 16 September 1949:

“…In the light of all that I have said above, I am sure you will review the matter again and not yield to some of the sentiments and feelings, which you have expressed in your letter to Jawaharlal…Let the matter blow over completely and you should dismiss from your mind that any distance can come between us. We shall be near each other as we have been all these years. Our mutual regard and affection have stood the test of a great struggle. All other tests through which these may have to pass are bound to be comparatively insignificant. We can talk about it further when I return to Delhi. For the time being, it would give me some relief if I got your assurance that you have dismissed this from your mind altogether.”

Nehru was to go on a five-week tour of the U.K. and USA on 6 October, and he wanted the decision in favour of Rajaji before his departure. He decided to place his proposal before the Congress party of the Constituent Assembly, which was to elect the first President. Patel tried to dissuade, but Nehru went ahead.

Here is a section from the minutes of the meeting by V. Shankar:

“As soon as he [Nehru] had done so, the atmosphere became tense. His speech was interrupted by some vociferous members; the interruptions were not quite dignified… Nehru was followed by a number of speakers who all opposed the resolution in strong and bitter words. The debate became acrimonious and there was no mistaking the overwhelming sense of the party against the proposition. It was at this stage that Sardar took the mike and made a moving appeal lasting for about ten minutes. He appealed for decorum and dignity and pointed out that notwithstanding differences, the Congress had always settled controversial issues to the general satisfaction of its members and it was unbecoming of them to exhibit such an attitude….”

Patel’s intervention saved Nehru from the defeat of his resolution. But that night Nehru informed Patel through a handwritten letter that he would resign after the trip. But immediately after returning to India, he started working for the election of Rajaji.

Nehru wrote to Prasad on 8 December 1949 about the pathetic situation the party had slipped to, the problems in the government, and offered Prasad the party Presidentship or the Chairmanship of the Planning Commission.

Prasad replied to Nehru on 12 December 1949:

“I agree that a decision regarding the Presidentship of the Republic should be taken without any further delay and if I can in any way help I am perfectly willing and prepared to render such help as I can…For some reason or other—justified or wholly wrong—there is a considerable opinion among the members of the Assembly who insist on my accepting the Presidentship of the Republic. From what I have gathered from the talk with the various persons who have come and seen me in this connection, it appears my not accepting the offer will be looked upon by them as a ‘betrayal’. They have used that expression and told me that I should not ‘betray’ them or ‘let them down’…”

Patel, by then, appeared to have decided in the favour of Prasad. He wrote to Prasad on 18 December, 1949:

“You know Jawaharlal’s views. You can guess what Maulana feels. In other words, you have placed the burden—and a heavy burden at that—on me. I really do not know what to do. Jawaharlal tells me that he will discuss it with me on my return.”

After this, Patel set things in motion. When asked by D.P. Mishra about the Prasad’s chances, Patel replied with characteristic dry humour:

“Agar dulha palki chhod kar bhag na jaye to shadi nakki.”

(If the groom does not leave the palanquin and run, the marriage is certain).

Patel was hinting at the mild, humble and self-effacing nature of Prasad, and feared that Prasad could allow himself to be persuaded to retire in favour of Rajaji.

Prof. Makkhan Lal is Founder Director of Delhi Institute of Heritage Research and Management and currently Distinguished Fellow at Vivekananda International Foundation.