Nawazuddin Siddiqui-starrer Manto humanises India-Pakistan conflict, shows it’s beyond guns and glory.

Most of us have grown up on a solid diet of nationalist films like Gadar and Border that teach us one thing – to hate our enemy, Pakistan.

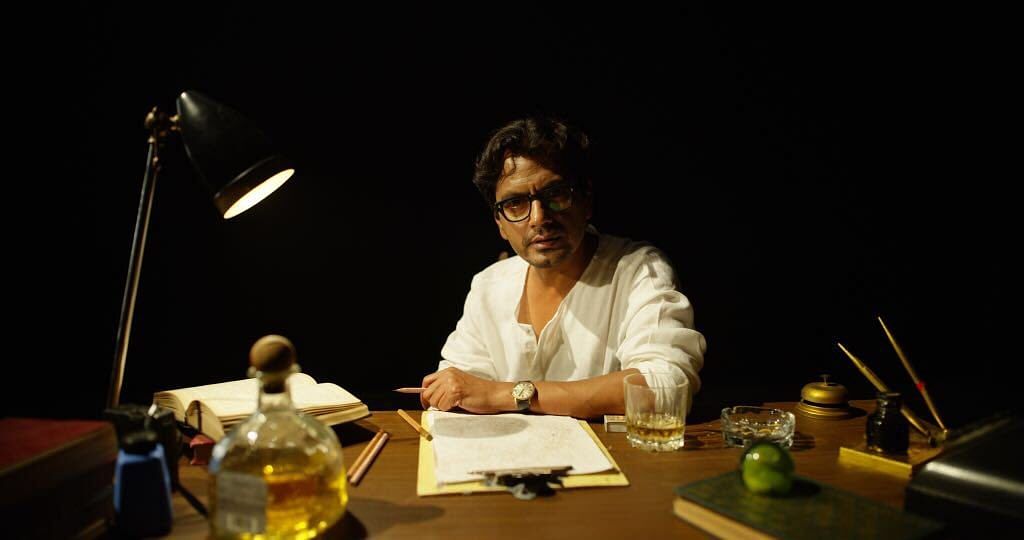

Nandita Das’ Manto, featuring Nawazuddin Siddiqui in the titular role, just turns this popular Pakistan-hating narrative on its head. The film, through poet-writer Saadat Hasan Manto, humanises the India-Pakistan conflict, and shows that the only losers in this battle are people on both sides of the border.

The movie doesn’t use the traditional tropes of Partition storytelling like graphic images of violence and bloodshed or hate-spewing dialogues or glycerine-induced tears.

So, when Manto asks actor Ashok Kumar in the film to wear a skull cap because they are passing through a Muslim-dominated neighbourhood, the actor declines. A minute later, a group of people approach his car. Manto senses fear and tries to roll up the windows, but can’t. The group by then, realising that it’s the actor car, is eager to shake hands with him, and even advises him which route to take.

Also read: What it was like to be on the sets of Nandita Das’ Manto

The scene while playing on the fear of a Hindu-Muslim divide exposes the pre-conceived notions we harbour about a community.

The first-half of the movie, set in the Bombay of the 1940s, takes off with Manto’s story ‘Dus Rupay’ based on a teenage prostitute. A bold cut later, we see Manto in his honest white kurta straightening his father’s frame on the wall during breakfast. The seamless transition from his stories to his life is filmmaking brilliance.

His finest works, from the celebrated and controversial ‘Thanda Gosht’ to ‘Toba Tek Singh’, are brought alive on screen, and intelligently used in carrying Manto’s narrative forward. The juxtaposition shows how Manto’s writings affected his life and how his personal experiences shaped his craft.

If you thought you have seen Nawazuddin at his best in Gangs of Wasseypur and The Lunchbox, then you are about to explore yet another side of the actor in Manto. In the Nandita Das film, he ceases to act and instead wears the writer’s skin, down to the impeccable Urdu pronunciation.

He essays Manto’s emotional turbulence and his determination to continue with his fiery writings all at the same time. His impassioned speech as Manto in the court on literature’s need to mirror the reality of the times is sure to stay on.

Unlike Manto, his wife Safia, played by Rasika Dugal, is more pragmatic. She appreciates his work, but minces no words while telling him that his writings may force the family into starvation. Dugal’s Safia is soft-spoken but not meek.

Also read: Nawazuddin wanted ₹1 for Manto— Promotional gimmick or Bollywood upholding artistic cause?

Manto is also a story of friendship, one between the writer and actor Sundar Shyam Chadda, or Shyam, played by Tahir Raj Bhasin. The film follows their friendship through its ups and downs. Manto is shocked when he hears Shyam, whose family has lost a member to the Partition violence, say that he may also kill Muslims. The incident shakes Manto to the core, changing the contours of their friendship forever.

Nandita Das’ Manto uses such personal stories to reflect on the loss and longing associated with Partition. For Manto, who finally migrates to Lahore, a part of his identity is left in Bombay, the city where his parents and his first child are buried.

Kartik Vijay’s cinematography takes the movie-viewing experience to another level. His generous use of close-ups of Manto with backlights heightens the character’s delusions, confusions and sense of loss.

Rita Ghosh’s production design ensures that the emotional and physical scars of Partition emerge through small motifs like a tilted frame of Jinnah.

Partition for the millennials has been reduced to a lesson in history, with few being able to grasp the enormity of the loss.

Also read: If Priyanka has to say sorry for showing Hindu terrorism, so should Sunny Deol to Muslims

It is to Nandita Das’ credit that she conveys the trauma of that experience without the high-voltage drama that we have come to associate with Partition movies. Her Manto is a fine tribute to the poet-writer.