Whatever position you take on the controversial dream project of Prime Minister Narendra Modi to redesign the heart of Lutyens’ New Delhi with the ambitious Central Vista project, you know that something will be irredeemably lost in the process.

My critique of architect Bimal Patel’s impressive Rs 13,450 crore makeover project is that it doesn’t have a plan to acknowledge, retrieve and repair this loss. It just doesn’t have a ‘historicising’ element.

All changes bring along tremendous anxieties, especially those that are disruptive and transformative like the 86-acre Central Vista redevelopment plan. These anxieties about losing the past must be addressed. It will go a long way in turning this contested initiative into a truly public one. Right now, the new Central Vista project has a history-shaped hole in its scope.

The Supreme Court will hear ten petitions opposing the Central Vista project, but nobody actually believes it will be struck down. With the bhoomi pujan at India Gate done, Modi should now focus on the role of the public and on preserving public history. The people’s history that resides in historic buildings just can’t be shifted to new glossy structures.

Also read: Parliament to Kashi Vishwanath: Why Modi always hires architect Bimal Patel for pet projects

Raise public stake in the Central Vista

Almost every rebuilding and revitalising project in countries like the United States or the United Kingdom is accompanied by a call to people to donate personal artefacts and oral histories – a kind of public history drive that harvests people’s memories of the space.

Modi’s new Central Vista project will go a long way in assuaging public criticism if it can enlist people to deposit their memories around the buildings that will be torn down, and assure them they will be preserved in the public archives, universities and displayed in museums. It can add an element of public participation to the mammoth project. It will be an acknowledgement that there was a lived past in these buildings before the bulldozers arrived.

This usually increases people’s stake in new projects and diminishes, over time, their sense of loss. Ctrl-alt-del is what empires do; it’s not suitable for a democracy.

National Museum history

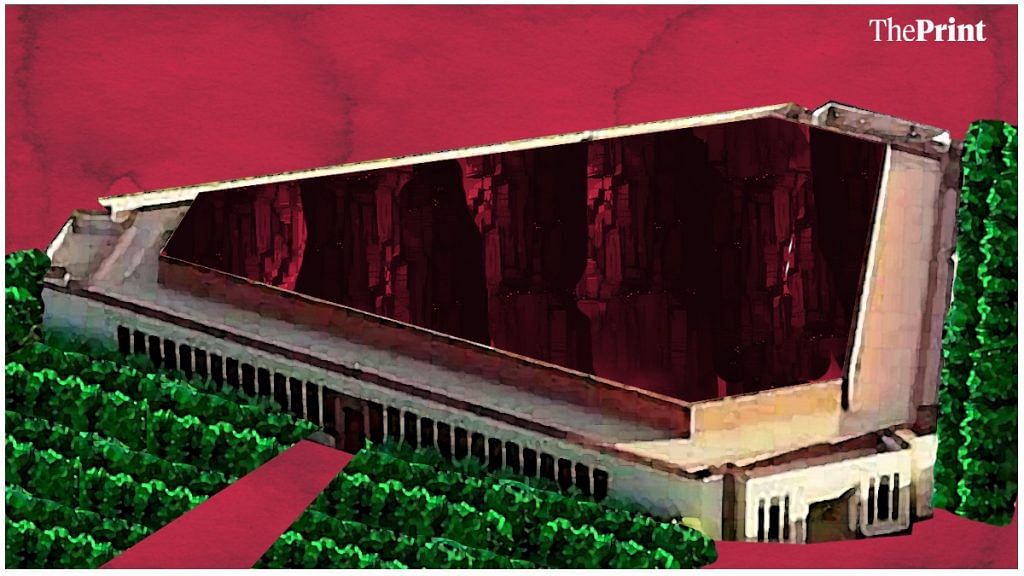

Apart from the many ministries, the iconic National Museum will also be taken down and shifted to the South and North Blocks. An office building will come up in its place.

The National Museum building (designed by the architect Ganesh Bhikaji Deolalikar who was also the first head of the Central Public Works Department) has a rich history. It was established after Independence to “celebrate the ancient culture of the young state” and its mandate was to show that India was “eternal” and “great”, wrote art historian Kavita Singh.

Soon after Independence, the Royal Academy in London held an exhibition titled ‘The Arts of India and Pakistan’. When they sent the artefacts back to India, the Rashtrapati Bhavan used them to set up a temporary exhibition. It was very well-attended, and this germinated the idea for an overarching Delhi-based museum. One of Jawaharlal Nehru’s ministers wrote to the owners of these artefacts across India requesting them to let the objects stay in Delhi.

Today, a significant portion of the National Museum’s collection remains locked in storage. Shifting to two larger buildings in the South Block and North Block will create an opportunity for many of these artefacts to see light, to be displayed and viewed by the public.

But when the National Museum is torn down, we must pay attention to not just the artefacts, but also its public memory. The historical details of Deolalikar’s work (who also designed the Supreme Court building), of Nehru laying the foundation stone and S. Radhakrishnan inaugurating it, the names of the invitees, the speeches, the first few visitors, their photographs and family memories; the details of how the building changed, how the museum runs a post-graduate degree course in museology, diplomas in art history and art appreciation and conservation (Congress leader Sonia Gandhi attended one course). Deolalikar’s family must be contacted for oral histories and memorabilia that they are bound to have.

Also read: Sonia Gandhi wants Modi to suspend Central Vista. But this urban harakiri must be scrapped

Ministries and memories

The only research into the past that Bimal Patel’s large team has done or planned for is to study the old architectural designs, conduct audit of the materials used and document the haphazard changes made to the structures in recent decades. They are doing a detailed photographic and video documentation of buildings. This research is valuable from purely an architectural point of view — to build new structures and to renovate old ones. But they don’t help in the narrative history project.

So far, there has been no effort to track down families of the old CPWD architects and designers of the ministry bhawans. Of course, some of them would be dead, but their families would be alive and may have some memories, letters, diaries, mementos. The first generation of government employees who worked in these buildings are a catchment constituency for any oral history project.

When IIC turned 50

Here’s an example of what public histories of old buildings can offer. When the India International Centre (IIC) turned 50, I was part of a team of oral historians that Srishti School of Design scholar Indira Chowdhury led. I conducted oral history sessions with early members of the IIC – to understand and preserve the intangible heritage of the building. These included capturing what the first few decades of the IIC looked like, the sense of pride in the unique Stein architecture, the landscape, its emergence as an important meeting place for intellectuals, and the meaning of Nehru’s ‘internationalism’ that is embedded in this institution.

Early members reminisced about the IIC elections, conversations in the lounge, VIP guests, who looked after the cultural events, gardens and the library. The IIC made this effort to dig into the history while older members are still alive. At least two of the half a dozen people I spoke to – Kuldeep Nayyar and B.G. Verghese – have since died. Oral history and artefact collection projects are always a race against time.

Also read: Modi’s Central Vista plan shows Indian urban planners are as complicit in destroying heritage

History of the Now

The problem is that Indians don’t regard contemporary history as history worth capturing. Many of the government buildings have existed in the heart of the nation’s capital for more than half a century and are worth historicising.

When we think of history, we think of ancient, medieval and colonial history. Similarly, our understanding of the museum institution is all about collecting archaeological and royal artefacts. Can CPWD engineers and architects and ordinary government employees in ministries and the Parliament building be considered history creators? It is time we upend our limited understanding of history, of what is worth preserving — and include contemporary public histories. We have to be mindful of what the next generation of scholars or the next century would be studying about our shared present. Oral histories are archived universities in developed Western nations and are considered precious primary sources for students’ papers. In the US, oral histories of the railroad project, civil rights movement and disability rights (I worked on the last one) are some publicly accessible examples.

This is why we need to be creating museums today like a grand IT history in Bengaluru, a museum of Indian democracy, or of Indian media history or economic history. The present Parliament Museum is good but it is mainly an institutional and political history. It does not include the memories and artefacts of people who work or have worked there.

Also read: Narendra Modi wants to rebuild New Delhi for no good reason

Time is running out

Of course, there are valid questions about whether such a monumental project should be a priority for the Modi government, given the constraints on budget in the current economy, the ongoing pandemic, the need to spend scarce money on real infrastructure of highways and ports, and that familiar logic of ‘don’t fix what ain’t broken’.

But that is precisely what Bimal Patel and his team are trying to tell us. That the old city centre is broken. That the buildings in the prime real estate of the country’s capital suffers from gross inefficiency in its usage pattern. Most of this valuable land has been turned into a sea of parking. The ministry buildings are spread across the city. Only 22 ministries out of 51 are located within the Central Vista area. And the Parliament building is old, unsafe and cramped.

But the ten petitions in the Supreme Court are about issues like transparency, consultation, permissions and land use. Many have criticised the project as an example of the emperor’s megalomania, Modi’s monumental ego and even called it a palace built on the ruins of a liberal democracy.

But none of them raise the issue of conserving tangible and intangible histories that we will lose forever. This needs urgent focus. Time is running out.

Bimal Patel likes to say that the new Central Vista’s goal is to “extend the vista and expand the public space”. Let’s bring the public into the project.

The author is the Opinion Editor at ThePrint. She is also the curator of Remember Bhopal Museum and has worked in several American museums, including the Smithsonian Institution. She has conducted oral history sessions with Bhopal gas tragedy survivors and American disability rights activists for the Missouri History Museum. Views are personal.