I learned about ‘Baba’ Mehar Singh while researching an article about my uncle who flew Hurricanes in Burma. He was my uncle’s squadron commander and the only officer in the Royal Indian Air Force (RIAF) awarded a Distinguished Service Order. It is usually awarded to honour leadership rather than individual bravery. Air Marshal Asghar Khan, who flew operational sorties in Burma in 1944, confirms that, “With the solitary exception of Squadron Leader Mehar Singh, a pilot of outstanding ability, no one was able to inspire confidence among us.” Field Marshal Slim considered Mehar Singh ‘an old friend’, an association which probably developed during the Waziristan Campaign when Slim was commanding the 2/7th Gurkha Rifles in 1938. As Commander Fourteenth Army in Burma, he was ‘very impressed by the conduct of the squadron’ led by Mehar Singh.

I knew little of him as an individual till I read the autobiography of his friend and contemporary, Wing Commander Aizad Baksh Awan, the brother of Ayub Baksh Awan, the Inspector General of Police. Mehar was born in Lyallpur and was in his final year of B. Sc. at the Punjab University, Lahore when he was selected for the three year course at the RAF College Cranwell in UK. He proved to be a first class pilot and his instructor openly declared that Mehar would have easily won the Groves Memorial Trophy for flying had the British Air Ministry not barred Colonials from competing for this prize after it was awarded to Aspy Engineer in 1933. Aspy was a Parsee who had been educated at the DJ College in Karachi and was a member of Awan’s Flight. He earned a DFC during the Second World War and was Chief of the Indian Air Staff from 1960 to 1964. In May 1936, Mehar Singh was also posted to Awans flight in No 1 Squadron at its Drigh Road Base, Karachi.

Mehar Singh was regarded by Awan as a brave flier with supernatural powers. His senses of touch, sound, and smell were superior to others, and his eyesight and reflexes were exceptional, making him an excellent shot. Out on the Malir River in early 1937, except Mehar Singh all the officers missed a partridge that zigzagged across the line of beaters. He would always wait with the clipped muzzle pointing down and drop the bird like a stone when it was nearly out of reach.

He had the appetite of an ox. Back from his wedding in Lyallpur in 1938, every night after dinner he would invite Awan to his tent pitched near the mess at Drigh Road because all the rooms were taken. “Zaidy, come and have a few luddoos.” They were made by a family of famous halwais in Lyallpur and of an enormous size. While his friends could only consume one, Mehar Sing ate 2-3 dozen as a tonic after a hearty meal that had already been rounded off with half a dozen oranges and an equal number of coffee refills. On a flight to Ambala, with Awan piloting and Mehar sitting on the rear seat of a Hart biplane, they landed at Jodhpur for refueling. Awan was hungry after supervising the refueling, but when he climbed into the rear cockpit for his lunch of omelets and four parathas it had vanished and the tea flask was empty. A guilty Mehar Singh who had forgot to bring his own lunch, had withdrawn to a corner of the apron.

He also drank like a fish. He believed that plain water was unhealthy for the stomach, but consumed copious quantities of every other liquid – coffee, tea, coca, and orange squash, all served in a big tumbler that as young officers we dubbed OR (other rank) glasses. Even Scotch and Soda were drunk from an OR glass, and he was able to top it off with beer, rum, and gin without any effect.

The pilots of the blossoming RIAF were weaned in the operations on the Northwest Frontier on the eve of the Second World War and it was an escape during his tenure with No. 2 Squadron in Waziristan, that Mehar Singh’s legend was probably borne. It’s a well document story in which he was shot down and crashed while bombing a village. He and his gunner evaded capture by a horde of tribesmen by hiding in a cave at night and had to keep at bay a pack of wolves who returned to their den. Every surrounding post sent patrols to retrieve the aviators who were found the next morning were heading towards Razzani Camp – dead tired, bruised and very hungry but alive.

Awan had given his friend the name Mehar Baba after a bearded Sindhi saint who enticed young women out of their homes, but Mehar Singh was terrified of the fairer sex and avoided them like poison. In 1946 when Mehar’s squadron was based in Bhopal, an Indian pilot told his pretty English wife Evelyn to stand next to the squadron commander at the bar. Eve wore a bedazzling evening gown with plenty of jewelry, powder, lipstick, rouge and mascara and a heavy dab of Parisian perfume. Wherever the bashful Sikh was talking to a group of pilots on sports and flying, Eve would slide up holding a glass of sherry and listen respectfully. When her perfume hit his nostrils, Mehar Singh would bolt to another group. For 45 minutes, Eve pursued Baba Mehar from one group to another and he eventually left.

He was a natural sportsman and played hockey for the Punjab University and later for the RIAF. Dara, the reputed Olympian said, “With Mehar playing fullback for the opposing team, no one can score a goal.” Mehar also took up golf at Drig Road and in 1939 won the Championship in Karachi against the best players in the city. He had never held a golf club and initially swung it like a hockey with a flick of his wrist. He then expanded his swing into a beautiful stroke and while on standby alert, would practice on the aerodrome.

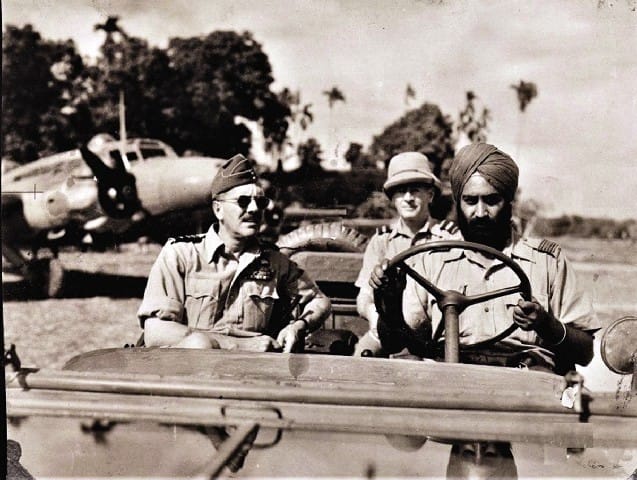

After commanding a squadron for six months in Peshawar in 1942, he was posted to No.6 Fighter Reconnaissance Squadron flying Mk 2B and 2C Hurricanes equipped with cameras. He proved to be a capable but eccentric squadron leader. While some flew in 1930 Pattern Flying Boots or in the 1943 Pattern ‘Escape’ Boots, or shoes with stockings, or ammunition boots with anklets, ‘Baba’ Mehar Singh preferred to fly barefoot! In his book, Defeat into Victory, Field Marshal Slim narrates that “I looked in at this squadron just at a time when news had come in that the last patrol had run into a bunch of Zeros and been shot down. The young squadron commander [Mehar Singh was only 29 years old], at once took out the next patrol himself and completed the mission. His methods, rumour has it, were a little unorthodox. It is said that if any of his officers made a bad landing, he would take them behind a basha and beat them. Whatever he did, it was effective. They were a happy, efficient and gallant squadron.” This was despite the fact that his squadron had the highest number of casualties and was dubbed the Suicide Squadron. Some incorrectly thought he was a heartless butcher but if one of his ‘boys’ was killed he shed a tear or two but only in front of his close friends like Zaydi. He was a disciplinarian and never smiled on parade but enjoyed a joke in the officer’s mess.

The Battle of Arakan seems to have magnified his appetite and thirst. When Awan visited his friend for a few days, during one evening, Mehar Singh “ […] put away four glasses of whiskey and soda before dinner. He then ate four full plates of hot curry and rice and one whole chicken. This was followed by a large serving of bread and egg pudding and a full glass of tea.” Soon after he had two more OR glasses of whiskey and a glass of orange squash in one gulp. At bedtime, his orderly Dhanna Singh served him a glass of hot cocoa.

There were two enemies in Burma – the Japanese and malaria. Mehar Singh battled the Japanese in the air in his Hurricane and on his charpai he battled the mosquitoes with whiskey. Awan was sharing the ‘Bhasha’ with Mehar Singh and was badly bitten by large mosquitoes that had penetrated through his net. On the other hand, in the morning his host was sleeping peacefully; his ‘charpai’ surrounded by mosquitoes killed by what Mehar referred to as “a lot of explosive material” in his body.

Also read: The British used ‘low-caste’ Indian soldiers only when WWI intensified, rejected them after

Awan credits Mehar Singh with the heart of a Bengal tiger, stamina and guts of a Punjabi bull and flying ability of a Himalayan eagle. On lone sorties he would penetrate hundreds of miles over Japanese territory photographing troop movement and concentrations from 20,000 feet. His qualities were visibly demonstrated in an incident when Shiv Dev Singh, one of his flight commanders was hit by ground fire but luckily landed his Hurricane in a clear patch of elephant grass. His tail-Charlie landed back and showed Mehar exactly where Shiv had force-landed. Mehar lost no time in taking-off in a Harvard with a mechanic, spare parts and tools. Shiv tried to stop him from landing by waving his arms but Mehar Singh touched down and after a few bad bumps came to a stop.

Shedding a tear of joy, Shiv frantically warned his squadron commander that a whole Japanese brigade was only two miles away. Both were aware or the horrendous beating that the Japanese inflicted on Indian pilots to break their moral. However, Mehar Singh calmly inspected the Hurricane and after confirming that the only damage was to the propeller, he took off with a great deal of bumps and bounces. Shiv and the mechanic followed in the Harvard. Though the Hurricane vibrated like crazy due to the damaged propeller, it made it back and the whole squadron lined the runway to receive them. For Shiv it was a new lease of life; for Mehar it was just another day’s work commanding a fighter recce squadron.

Mehar had the best qualities for a combat leader and continued to lead from the front in the First Kashmir War as AOC No.1 group controlling operations in Kashmir. He was the first to pilot a Dakota into Srinagar and the first to establish an air bridge into Poonch. He was also the first to land on a dirt strip at Leh. His entire service had been spent in war zones and he probably could not adjust to the constraints of peacetime operations and retired in 1948 over differences with some senior officers.

Mehar never thought that a he would die in an aircraft. He used to tell Zaidy “Old pilots never die; they just fade away.” Unfortunately, he was killed while piloting a 3-seater aircraft through a thunderstorm between Ambala and Delhi. He died at the age of 36 but his legend lives on.

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Jagan Pillarisetti for assisting me with information and photographs and for vetting the draft.

The article originally appeared in The Friday Times.