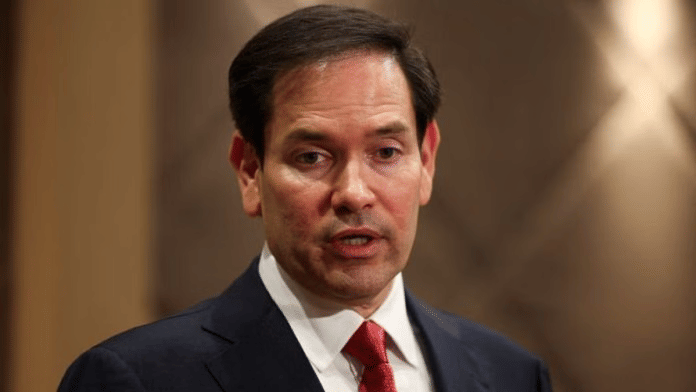

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s speech at the Munich Security Conference was widely welcomed in Europe but criticised elsewhere. It was no doubt a strange speech, but its logic becomes clearer if we see it as a balancing act. Rubio has been a traditional, conservative Republican politician, but he also wants to be a faithful member of the Trump cabinet.

It is widely recognised that Rubio is competing against Vice President JD Vance to be the next Republican presidential nominee. He is thus trying hard not to lose Trump’s MAGA base, but is also struggling to entirely junk his own Republican roots.

It is doubtful that Rubio will succeed in this delicate balancing act. As a traditional Republican, his foreign policy orientation is firmly that of an internationalist who believes that the US has a role to play in global affairs—partly because of American values but mainly because of American interests. This means strengthening American military power but also American leadership through alliances and partnerships, even with some occasionally nasty types.

If Europeans applauded his speech, it was because they saw elements of this old Washington foreign policy sensibility in what Rubio was proposing. This was visible particularly in his idea of Europe and the US having to come together today, but also sharing a centuries-old partnership when they fought common adversaries and promoted common values. This is a vision that Europeans desperately want to return to, and they are willing to put up with some nonsense about civilisational values if that is what it takes.

This is radically different from Trump and Vance’s argument. Of course, it is unclear what Vance believes in—beyond using others as stepping stones to power. Trump, at least, has a few strongly held beliefs, even if they make little sense to most people who think about geopolitical issues in any disciplined manner. At this moment, however, Vance has learned to convincingly mouth Trump’s half-baked and ill-defined thoughts as if they are something of substance. This is what Rubio has to find common ground with, because it’s the current state of “thinking” within the MAGA Republican foreign policy establishment.

Courting MAGA

For both Trump and Vance, Western Europe is the enemy, while Russia is a partner. The basis of such beliefs is difficult to fathom. It appears to be based on Trump’s belief that American allies have exploited the US, which is one of the strangest ideas to come out of Washington. It has no basis in the spectrum of American strategic thinking before Trump for the very simple reason that it is absurd. But it is one which Trump holds with some fervour as a purely personal belief, which is now a MAGA standard. This is why Trump doesn’t want multilateral trade or security arrangements with Europe or others.

Rubio’s invoking of US-Europe civilisational links is most likely part of his effort to curry favour with the MAGA base, even if it sits uneasily with Rubio’s traditional foreign policy views. Invoking civilisational links with Europe allows Rubio to stay within the lines of the unevenly racist Trumpian elite. It appeals to the vague MAGA notions of some traditional past glory that needs to be revived, but it also allows Rubio to slip in a US-Europe partnership that appeals to the old Republicans.

Such sophistry is unlikely to fool the MAGA base, when Vance can appeal to a stronger sentiment in which Russia is the inheritor of European values while Western Europe is a lost cause. Rubio has been known to be too clever by half, but it remains to be seen whether he can keep his footing in both traditional Republican and MAGA camps. But given the uncertainty about where the Republicans go after MAGA, perhaps Rubio has as much of a chance as Vance, who has all the charisma of charcoal.

Also read: India’s improved ties with China expose cracks in the Beijing-Islamabad relationship

Civilisation as ideology

Beyond the domestic politics is the substantive question of whether Rubio’s notion of civilisational foreign policy makes any sense because the idea has had appeal in many parts of the world, including India. Simply put, does civilisation affect the international behaviour of countries? It doesn’t. Rubio himself referenced the two world wars, in which European countries fought against each other with great vigour. The pattern of intra-European wars is as long as European history. The only break was when Rome conquered much of the continent and imposed a Roman peace, or Pax Romana. This was resisted by various sub-nationalities and tribes throughout the period of Roman rule—hardly an advertisement for a common civilisation.

Europeans were no more divided than any other region, of course. Across the world, divisions were the norm rather than civilisational unity, except where such unity was imposed by force of arms. Sure, there are common cultural elements and historical experiences, which can be seen as ‘civilisational’ and which mark differences between regions. But the question is not the existence of civilisations or civilisational values, but whether they have any impact on the foreign policy behaviour of states.

If ‘alliances’ were indeed determined by civilisational links—as Rubio seems to imply—how do we explain the disagreements between Russia and other European states? Or consider another possibility: Do civilizational traditions determine foreign policy attitudes, or how the foreign policy elite think about issues of strategy? This would require us to be able to see some commonality in elite attitudes. But we see no indication that elites think alike on such issues. Political ideological influences, personality factors, and other imponderables appear to lead to greater disagreements than can be overcome by any civilisational unity.

But if ‘civilisation’ is useless as an analytical category, what explains its recent political popularity? Most likely, it plays the same role today in parts of the world that various political ideologies have played at other times. It is emotive and provides a source of common identity as well as a set of adversaries that help unite the community, irrespective of its shaky foundations.

But ideologies were never a source of behaviour, either. Power and interest have a habit of shaping it in a far more predictable manner. So, as a guide to behaviour, the latest ideology of civilisation will fare no better.

Rajesh Rajagopalan is a professor of International Politics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He tweets @RRajagopalanJNU. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)