So, who invented the printing press? Gutenberg, right? Well, no. The first printing press was invented in Korea. Yes, Korea. The Koreans were the first to print something using a movable cast metal printing press. They printed Jikji, the oldest metal-printed book, 77 years before Gutenberg’s Bible in the 1450s.

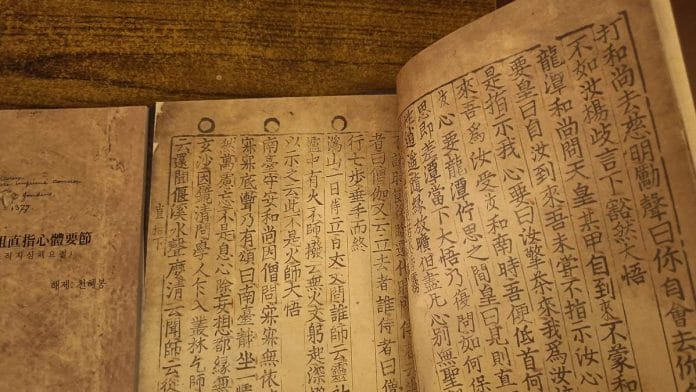

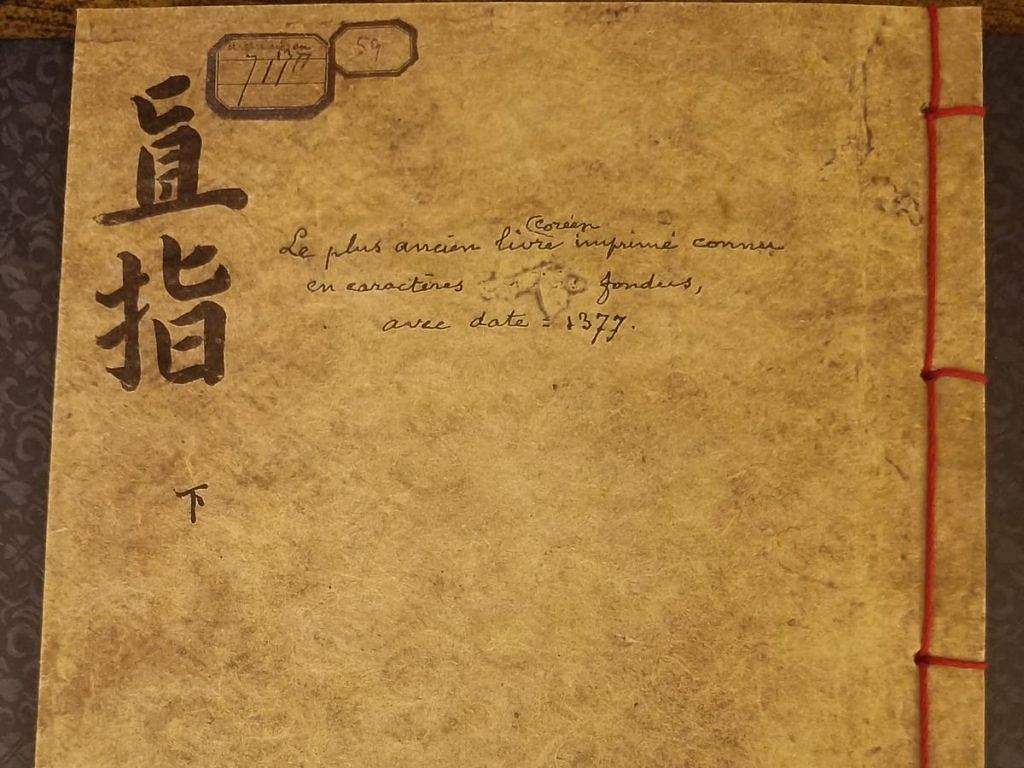

Jikji, short for ‘Jikji Simche Yojeol’—meaning ‘Essential Passages Pointing Directly to the Mind—is a collection of Buddhist treaties, laws, and scriptures. It was printed in 1377 during the Goryeo Dynasty. The fact that it preceded the Gutenberg Bible came to light relatively recently, prompting several historical projects in the West to verify the differences in the two types of printing methods and other details. UNESCO recognised Jikji as the oldest extant metalloid type of printed text in 2001.

Unlike the Gutenberg printing press, named after its inventor Johannes Gutenberg, the Korean press takes its name from the first book it printed. It doesn’t have one inventor but was instead put together by a team of Buddhist monks who were the disciples of Master Baegun who lived from 1298-1374. The only surviving copy of Jikji is in the National Library of France.

Also Read: South Korea building on K-pop craze to boost art scene. And India is part of its ‘big mission’

A story of perseverance

Printing in China and Korea dates back to as early as the 8th century AD—well before Jikji. In those times, with Korea at constant risk of invasions, mainly from the Khitans and the Mongols, its Buddhist monks were always in search of ways of pleasing Buddha and invoking his protection. This led them to undertake the extremely arduous process of printing the ancient Buddhist treatise Tripitaka Koreana, known as ‘P’alman Daejanggyeong’ in Korean, meaning 80,000 Tripitaka.

The text of this first massive book was typeset using wooden blocks, which were meticulously and painstakingly carved with the lateral images of Chinese characters. More than 80,000 (81,258 to be precise) wooden blocks were carved like this. These were then filled with ink, after which individual sheets of rice paper were pressed against them, thus printing the text onto the paper. These papers were then sewn together to form a book.

This formidable exercise, which took many decades, was undertaken during the Goryeo period (918-1392 AD)—a time marked both by foreign invasions and Buddhism as the state religion, resulting in state funding and protection. Many temples and pagodas in Korea, too, owe their origin to this period.

However, sadly, despite their efforts to invoke Buddha, the first and second books that were so created could not be saved during the Khitan invasions in the 11th century and the Mongol invasion in the early 13th century. But, the Koreans were not ones to give up easily. The monks then undertook this laborious exercise for the third time, compiling the book at Goryeo’s new capital on Kanghwa island, which was quite far from the line of foreign attack.

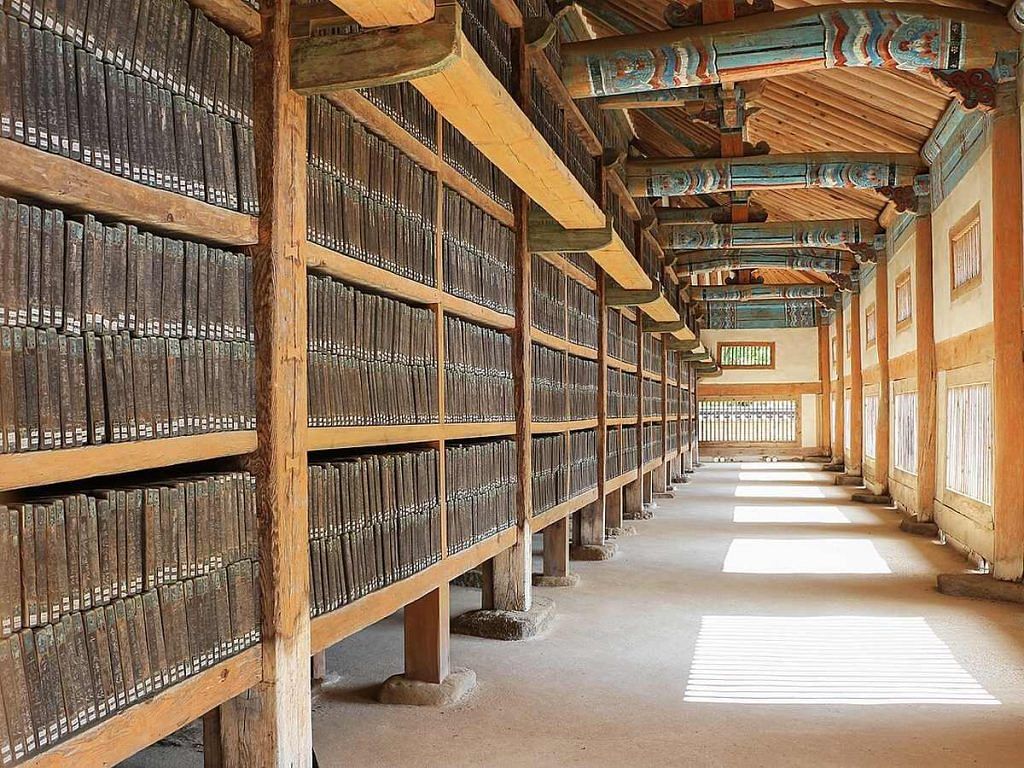

Korean ingenuity is evident both in the way the wooden blocks were cured, but also, later, in their conservation technique. The wooden blocks can be seen even today at Haeinsa Buddhist Temple in southwest Korea. Each of the 80,000–odd wooden blocks measures a uniform 24 centimetres in height and 70 centimetres in length. The wood, believed to be birchwood, was cured by first soaking it in seawater for three years. It was then cut and boiled in saltwater and then further exposed to the wind in the shade for another three years before being carved. Thereafter, the blocks were polished with an insect–repellent lacquer. Each of these blocks were placed vertically in slats for easy access. They are still completely usable and the complete Tripitaka can be reproduced even today.

Not just this. A lot of thought also went into the building of the room or the depository, known as the Janggyeong Panjeon, where these blocks are preserved. Within the Haeinsa Temple complex the depository is on the slope of Mount Gaya and consists of two large and two comparatively smaller rooms arranged in a rectangular form around a courtyard. These were designed not only to provide easy access, but to also ensure good ventilation and modulation of temperature and humidity.

All this ensured that, to this day, the wooden blocks remain free of termites and other insects or rodents. Nor have any of them warped or deformed due to changes in temperature. The government of South Korea ensures that they retain their original character by periodically undertaking renovation of the building.

Also Read: Indians are starting a love affair with South Korean universities. K-pop is the gateway

Jikji’s journey to France

How did France, which was not even a coloniser of Korea, come to possess Jikji?

It is said that Victor Collin de Plancy, the French consul and an avid art collector, was posted in Seoul during the latter half of the 19th century and acquired several hundred ancient Korean books, including Jikji, whose value was little known then.

Upon returning to France, he sold Jikji to another collector, Henri Vever, in 1911. Vever, in turn, bequeathed it to the National Library of France in 1950.

Jikji is a rare sight—the library puts it on display to the public only once in about 50 years. It was most recently on display in 2023.

This remarkable book is another instance of an important fact about East Asia, South Korea in particular, that has remained hidden and deserves more recognition.

Vyjayanti Raghavan retired as a Professor at the Centre for Korean Studies at JNU. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)