Some years ago, I was busy criticising Nehru’s economic policies. My good and worthy friend, the economist Dr Vijay Kelkar, stopped me in my tracks and cogently argued that in the 1950s, Nehru’s approach was not very different from that of Japan after 1868. Needless to say, I drew a deep breath and restrained myself from making a fool of myself all over again.

The Trump era has brought everything out from under the carpet. I taught courses on globalisation at IIM Ahmedabad, IIT Bombay, and Loyola Institute of Business Administration in Chennai. My argument was always centred on the cost of microwave ovens. I argued that globalisation and foreign (read Chinese) manufacture of ovens meant that America’s poor could benefit from low microwave prices and, in effect, become richer if incomes were measured in terms of actual goods like microwaves.

Now Trump, who articulates himself in a haphazard way, tells us that cheap microwaves, or for that matter cheap cell phones, which are all consequences of global trade, are not the only things that matter. There is something called national security. If a country stops making microwaves, phones, and even mechanical toys, over time that same country finds it difficult to build ships and almost impossible to make crucial military hardware, which needs specialised magnets. It is important to remember that the great free-trade advocate Adam Smith did want Britain to retain a strong navy. I am not sure if Smith extended this line of thinking to ship-building.

High tariffs and the protection of indigenous industry were advocated more than two hundred years ago by Alexander Hamilton, an American Founding Father who no one can accuse of being a socialist. This was pretty much what Pandit Nehru advocated as well.

And in different ways, through Atmanirbhar Bharat, PLI schemes, the revival of rare earths production, domestic production of APIs, and a renewed focus on ship-building, India is once again contemplating an old question. Not where one can get the cheapest price, but what confers greatest security.

Also Read: US bullying spurred Green Revolution. Let tariffs give us a Business Revolution

Where India went wrong

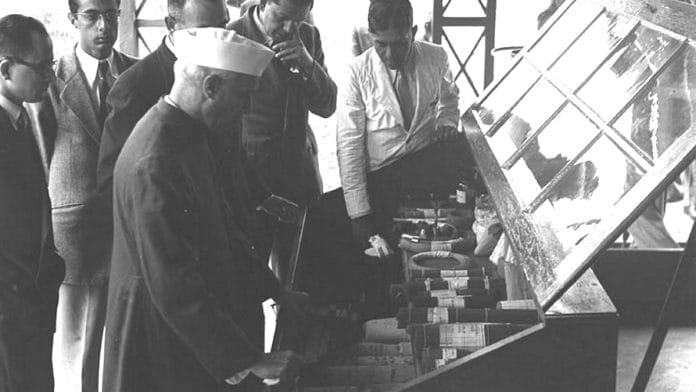

Nehru wanted industries such as steel and machine tools to come up in India because he was sure that, in their absence, we could not create a modern economy in a “secure” and atmanirbhar (“self-sufficient”) way. In a largely illiterate country, Nehru also supported the development of human capital through the IITs, an idea the brilliant Nalini Ranjan Sarkar had proposed in 1945. This was not radically different from the strategies followed by Japan or South Korea. So then, where did we go wrong?

We certainly did go wrong, because South Korea, which was as rich or poor as us some sixty years ago, is today an order of magnitude richer. I recently read in an article that the Cochin Shipyard Limited was established in the same year, 1972, as the Hyundai facility in South Korea. As of today, Hyundai has built 5,000 ships and Cochin has built 241. That must surely tell us something.

The only conclusion one can come to is that Nehruvian economics failed not in conception, but in operational implementation. The big mistake seems to have been an obsession with putting everything in the public sector.

If Hindustan Aircraft, which had been started by Seth Walchand Hirachand, had been left as a private company, we might today be selling planes to Brazil instead of buying Embraer aircraft. The pioneering Walchand also established the Hindustan Shipyard in Visakhapatnam. If this had not been nationalised in a frenzied hurry, who knows, it might have become a Hyundai. Biren Mukherjee’s Indian Iron and Steel Company, which did genuinely pioneering work, was allowed to be decimated by obdurate trade unions and was eventually nationalised.

The worst aspect of the public sector was that Nehru allowed himself to be trapped by our bureaucracy.

Outfits like Hindustan Steel and the Neyveli Lignite Corporation ended up being run by civil servants who ensured they grabbed all these assignments. Nehru did not consider bringing in engineers or commercial executives to manage these enterprises. Contrast this with Pohang Steel in South Korea, a public-sector company and one of the lowest-cost steel producers in the world. Nehru even told JRD Tata that he hated the word “profit”. He ended up with erstwhile District Commissioners running public-sector companies with dismal, often negative, returns on capital.

Nehru’s imaginative attempt in the mid-1950s to recruit Kurt Tank, the former Focke-Wulf designer, to work on what later became the HF-24 Marut was quite visionary. The whole venture, however, got lost in India’s labyrinthine bureaucratic morass—delays, fault-finding and finally abandonment with no evidence of constructive risk-taking or resilience.

Japan promoted private national champions like Mitsubishi and Hitachi; South Korea promoted Hyundai and Samsung. The Indian Parliament, by contrast, was full of resentment and malice towards India’s business community.

In the Lok Sabha, words like Tata and Birla became almost terms of abuse. And mind you, not all of this rhetoric came from Nehru’s own party; it was widely prevalent among opposition MPs as well. A country cannot progress if it abuses and shackles its entrepreneurs, its businesspersons, its wealth-creators, and instead hands over the so-called “commanding heights” of the economy to risk-averse bureaucrats who are prisoners of process rather than votaries of results.

Good intentions marred by mistrust

Nehru was able to withstand many pressures. Why did he succumb to a dislike of Indian businesspersons and end up being trapped by his bureaucracy? Like many things about us, much of this goes back to background and nurture.

Nehru came from a landlocked state where wealth was largely derived from land. His lawyer father’s clients were mostly zamindars and taluqdars locked in complicated inheritance disputes. These clients never worked. They lived off rentier incomes. Nehru probably acquired a dislike for rich people at that time. If Motilal’s clients had been mill owners and factory tycoons, perhaps Nehru might have noticed the difference between people who take risks and those who live off feudal patrimonies. Mingling with effete upper-class Fabians in London was a disaster. These Fabians were wealthy. They never worked. They liked talking. And they talked about the poor, whom they never met. Nehru may well have imbibed a dislike for industrial entrepreneurs there.

Nehru was shackled by two issues. The first was that India was a food importer, and agricultural production simply did not catch up. The second was that banning and controlling intermediate imports became an obsession because of foreign exchange paucity. It was a different age. No one thought to suggest depreciation of the currency, rather than import controls, as a more efficient solution. Charan Singh opposed the naive optimism that collective or co-operative farming would solve agricultural problems. He even resigned from the Congress. The Swatantra Party also opposed these measures. While they had partial success with agriculture, they failed with industry. Congress Party members were suspicious of businesspersons. The vocal PSP, SSP, and CPI groups were not suspicious. They were hostile. These forces prevailed and, ever the democrat, Nehru insisted on paying attention to these loud voices.

The result was that Atmanirbhar Bharat became an island of high costs, inefficiency, and ultimately enduring poverty. Incidentally, all attempts at reform, even tepid ones, came only after the Green Revolution eliminated the food shortage albatross.

In any event, today it seems clear that Nehru’s stress on tough industries—and doubtless steel and machine tools are tough ones—and his intuitive concern with security, not just low prices, were not misplaced.

What went wrong was that instead of supporting, encouraging, and building up Indian businesspersons, he opted to implement his ideas through state ownership and the bureaucratic machine, which for all practical purposes trapped him.

Also Read: West Bengal is almost beyond redemption. Messi’s visit exposed the long decay

A time for cautious optimism

One can be a tad more optimistic today about the revival of Nehruvian economics without the public-sector albatross.

Space, defence, and atomic energy have been opened up to the private sector. A hundred flowers are blooming and more will bloom. Many may wither away. A robust Japan/South Korea-style ecosystem, however, seems to be in the making. The present dispensation should have no hesitation in supporting national business champions, both big and small. Our present Prime Minister’s track record of ensuring efficiency in Gujarat’s public-sector companies lends an added aura of optimism.

But even as we embrace Nehru’s economics and avoid his operating errors, it bears remembering that for too long India has been a country of promise and potential that never quite gets fulfilled.

This time around, the execution has to ensure that national security is enhanced and that India stays at the cutting edge of entrepreneurial efficiency. This writer is too old and may not live to see the results. Yet, even the thought that good results may come in the not-so-distant future is a cause for pleasant optimism.

Jaithirth ‘Jerry’ Rao is a retired entrepreneur who lives in Lonavala. He has published three books: ‘Notes from an Indian Conservative’, ‘The Indian Conservative’, and ‘Economist Gandhi’. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Very well said sir… We the children of 90s were also fed the theory of free imports would bee good. And that’s not wrong but any good idea can be taken too far as EU and US are finding out. We need to make sure that going fwd no one holds a gun to our heads and our economy and security are robust