Whilst there are newspapers that I would unreservedly applaud I’m afraid there isn’t a single channel I can say that of without biting my tongue because I know I’m fibbing.

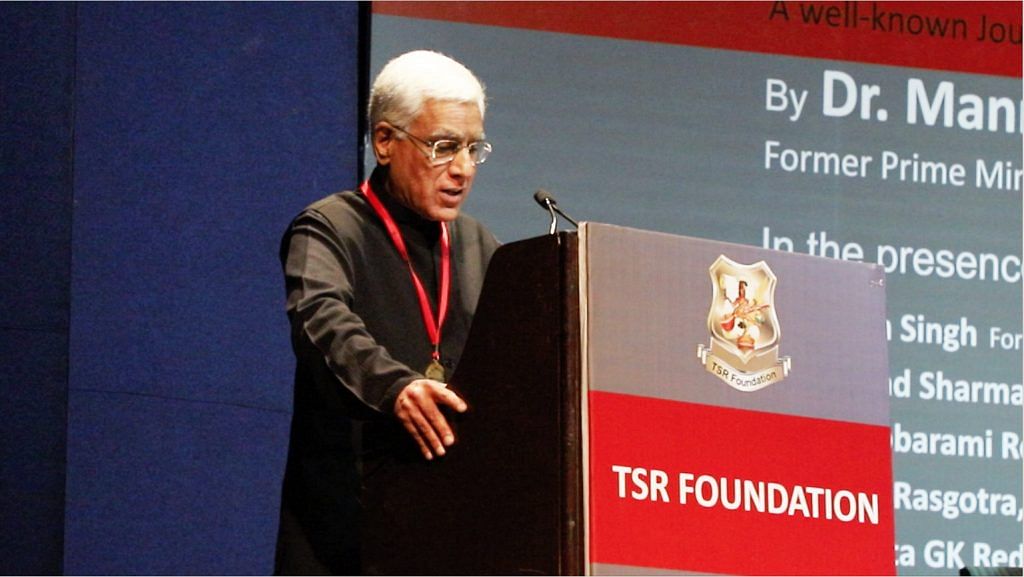

I’m honoured and indeed deeply flattered to be given the G. K. Reddy Memorial National Award and so let me begin with a huge thank you. Arthur Conan Doyle once said that work is its own rewards but it doesn’t need the genius of Sherlock Holmes to realise that a little recognition is a wonderful thing. And what more could any journalist ask for than to be remembered and recognised alongside the legendary G. K. Reddy?

Sadly I did not know Mr Reddy but who is there in my profession that does not know of him? His grasp of Indian politics and, more importantly, his understanding of Indian politicians have rarely been equalled and certainly not surpassed. Even three decades after his death the standard of excellence he effortlessly established remains the bar the rest of us struggle to reach.

There is, however, one small area where I can claim to have something in common with Mr Reddy. He served for many years as a distinguished foreign correspondent in Great Britain. During this time his weekly letter from London was widely read and greatly appreciated. I’m told he grew fond of the country and an admirer of the British people. I began my career in the same city and it’s always had a special place in my affections.

Today it may sound paradoxical but it is an amusing truth: I began my career as a journalist because of a fortuitous accident or, at least, good luck. In 1980, whilst struggling over my PhD thesis at Oxford, I wrote to 6 newspapers offering myself for employment. Four did not bother to reply. One simply said no. But the 6th, in the shape and form of Charlie Douglas-Home, then deputy editor of The Times, invited me for lunch.

Charlie was Scottish and he took me to the Caledonian Club. Pretending to be offé with food I was unfamiliar with I ordered Haggis. “Are you sure you want that?” Charlie asked. Sensing I’d done something silly I felt my honour demanded I stick to my choice. Little did I realise Haggis was the inside of a sheep’s stomach. Its taste is revolting.

“Serves you right,” said Charlie, when he saw I was gagging over the dish. He made me eat all of it. As I did, Charlie asked ceaseless questions and let me go on and on until he suddenly interrupted: “You seem to have a way with words even when you don’t know what you’re talking about. I guess that means you could be a journalist!”

But what clinched it was a rare error by Charlie. As we walked out of the club he said: “You’ve done the opposite of Norman St. John-Stevas”. “No” I shot back. “I’ve done the same”.

St. John-Stevas was a colourful minister in Mrs Thatcher’s government who had done his first degree at Cambridge before moving to Oxford for a PhD. So had I.

“Let’s go to my office and check,” Charlie insisted. “If I’m wrong the job’s yours”.

I’m not sure what would have become of me if Charlie had been right!

My life in television began a few years later. But, once again, luck played a big part. This time the credit for what I’ve learnt about interviewing goes to a very different sort of man. Unlike Charlie, John Birt was strong, silent and a structural analyst. As Director of Programmes at London Weekend Television, he was my boss. His glory days as Director General of the BBC were a few years further into the future.

“There are only 4 possible answers to any question” John used to say. “Yes, no, don’t know and won’t tell. Your job as an interviewer is to collapse don’t know and won’t tell into either yes or no”. Unfortunately, that’s easier said than done.

It is John I hold responsible for the fact many of you think I’m often aggressive or even rude.

“If a question is worth asking” John maintained “it’s worth ensuring it gets an answer. So if your guest evades or prevaricates, waffles or changes subject it’s your duty as an interviewer to bring him back on track. If you fail not only will he run away with the interview but it’s an insult to the audience who are waiting to hear the answer to your question.”

John, therefore, advocated firmness but he also equally stressed that the interviewer must always be polite. That, I fear, is a bit of his advice I sometimes forget!

All of that happened not only in another country but almost in another world. John worked in an environment where ratings were not the prime consideration for judging current affairs programmes. Content was always more important. Alas, it’s often the other way around in India today. If enough eyeballs are glued to your programme you can virtually get away with anything. Most of the people I know believe the media frequently does.

Which brings me to the question what would G. K. Reddy have made of Indian journalism today? Would he applaud his successors? Or would he cringe with despair? Would he feel the flower has brightened and blossomed? Or would he sense it’s starting to shrivel up and even rot?

The answer lies perhaps in two great changes that have occurred since the 60s, 70s and 80s, which are the decades when G. K. Reddy was compulsory reading in the Times of India and Hindu.

First, the reputation the media once enjoyed for reliability, balance and accuracy has suffered. Today you often hear the put down just because it’s in a newspaper doesn’t mean it’s true. Social media may have spawned fake news but the fact people rely on Twitter or WhatsApp to find out what’s happened suggests they no longer trust a paper or news channel to tell them the truth or the full story.

Connected to this is the claim the media could once make of being objective and fair. Few people are prepared to believe that today. Without double checking or giving a person a right of reply and often without knowing the full story the media judges individuals and finds them at fault. I don’t deny there are occasions when we’re right but every time we’re wrong we condemn an innocent person and leave him with little opportunity to correct the prejudiced image we’ve created.

The truth is whatever you make of the promise of achhe din, these are not good times for the Indian media. Most people I know have formed an irrevocable impression that it’s become pusillanimous. Where once newspapers and television channels boasted of challenging and exposing the government we now flinch from doing so. Worse, when our voices are raised it’s against the government’s opponents and critics – particularly those who have the gall to question the Prime Minister or the Army Chief. Instead of watchdogs that should growl at the authorities, even if occasionally mistakenly so, the media behaves like guard dogs, who seek to protect, or pet dogs, who just wish to be liked.

The saddest part of all this is that it’s the electronic media, of which I’m a part, which is widely thought to be the most to blame. Whether it’s our interviews of the prime minister, where we refuse to challenge and sometimes even to seriously question, or our panel discussions, where volume and heat is deliberately preferred to substance and light, or the crude hashtags we deploy on the screen, which are like drumbeats designed to marshal or dragoon the desired response, the net result is we fail to speak truth to power but also treat viewers like dumb animals who cannot see through our tricks and will not demand better.

We’ve even reached the stage where the Chief Justice of India in open court has had to admonish the electronic media and instead of standing up in our defence newspaper editorials have agreed with him.

This is what the Business Standard had to say on Monday: “There is little doubt that the abandonment of fact-checking and of even a pretence to fairness by the electronic media have put into jeopardy not just freedom of speech but also the smooth working of democracy itself.”

Of course, television, as we know it today, did not exist in G. K. Reddy’s day. In his time Doordarshan was the plaything of our rulers and rightly reviled. Today we have over 500 independent news channels and Mr Reddy might perhaps be flabbergasted at the number. But if he were to ask a simple question I wonder how many would stand up to that critical test: Is there a channel India can be truly proud of just as the British are justifiably proud of the BBC or the Americans of CNN? I’m not sure what his answer would be and, to be honest, I’m scared to find out yours. But let me end by sharing mine. There are some channels I’m proud of some of the time, some programmes I’m proud of most of the time but there are also a few channels and programmes that make me cringe all the time. Whilst there are newspapers that I would unreservedly applaud I’m afraid there isn’t a single channel I can say that of without biting my tongue because I know I’m fibbing.

But this is not the hopeless situation it might seem. After all, the media changes every day. Each edition of a newspaper and each bulletin of a news channel is a chance to begin afresh. A new reporter, a different anchor, a better editor and everything could change very quickly. Perhaps more than any other profession journalism can draw hope from the fact tomorrow is another day.

Ladies and gentlemen, I thank you for indulging me and I’m deeply grateful to the G. K. Reddy Memorial Award Committee for this opportunity to share my views.

Karan Thapar’s speech while accepting the G.K. Reddy Memorial National Award for Journalism at Teen Murti Bhavan in New Delhi, 22 March 2018.