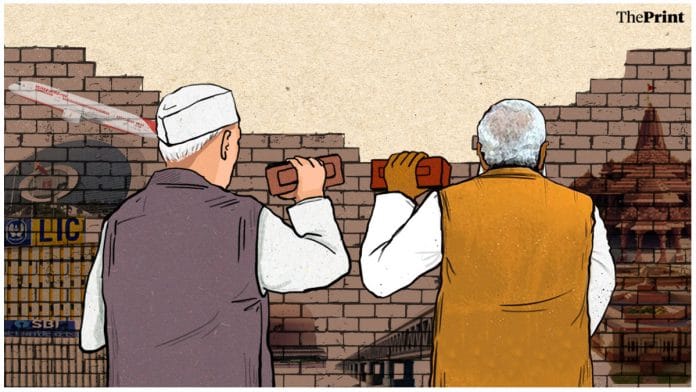

Narendra Modi has emerged as a builder whose multifarious projects have imprinted themselves on the physical map of India, and its mental space, as perhaps no one has done since Jawaharlal Nehru. Whether it is refashioning government structures at the heart of New Delhi, building a new Parliament House, and constructing the world’s tallest statue, Modi has embarked on projects that have symbolic and demonstration value. For good measure, he has implanted himself firmly in the Hindu qua Hindu mind by laying the foundation stone for the Ram temple at Ayodhya, inaugurating the Kashi Vishwanath corridor in Varanasi, and pushing through the Char Dham road projects to better connect ancient places of pilgrimage in the Himalayas.

More substantively in terms of resources, his government has committed vast sums to the country’s physical infrastructure: Linking the Ken and Betwa rivers (the first on an unreal list of 30 such), new highways and expressways, a “bullet train”, high-speed freight corridors, new airports, and major bridges for better connectivity in the northeast that include the country’s longest rail-cum-road bridge (4.9 km) and the longest bridge (19 km).

These multifarious projects invite comparison with the country’s first prime minister. Modi, on his part, has straddled the physical as well as cultural-religious spheres — the latter in order to establish a larger-than-life image for himself while cementing his party’s position in its core support base. In comparison, Nehru focused on building what he called the temples of modern India. The result was major hydro-electric projects (Bhakra-Nangal, Hirakud, Rihand, and the Damodar Valley Project); a base for heavy industry with a remarkable range of new enterprises to make steel, thermal power plant equipment, steam and diesel railway locomotives, railway coaches, battle tanks, and much else; and the city of Chandigarh.

He also built more than physical structures, since he founded the space and atomic energy programmes, set up the institutes of technology and new agricultural universities as well as a range of research institutes, and created a modern statistical system. Through nationalisation and consolidation, he set up strong corporate entities like the State Bank of India, the Life Insurance Corporation, Indian Oil Corporation, the Oil and Natural Gas Commission, and Air India (which was very well regarded during the Nehru era, even helping Singapore to set up its international airline).

Also Read: Twitter gets Indian CEO? Meh. Not all desi success stories call for song & dance

Similarities and contrasts

Perhaps the comparison is unfair to Modi since he has been in office for less than half of Nehru’s 17 years. The counter would be that much of Nehru’s initiatives and projects belonged to his first decade as prime minister, in a country handicapped at the time by infinitely smaller resources, a population more than 80 per cent illiterate and with life expectancy in the mid-30s. Impressively, Nehru raised by 50 per cent the level of savings and investment (in relation to GDP) while quadrupling the economic growth rate.

The equivalent for Modi in terms of institutional capacity-building would be the creation of the digital infrastructure that has enabled the digitisation of the financial sector, mushrooming of start-ups, and better targeting of government benefit programmes. He has also moved to re-orient the economy to deal with climate change, and is committing big budgets to incentivise a fresh burst of industrial development.

The two records have similarities and contrasts. Both have been modernisers, but Modi is also a revivalist. Both (have) under-emphasised the foundations laid by more successful east Asian countries: Quality universal school education, and basic standards of health and nutrition. Modi’s critics will say that he has put up cement and steel structures but weakened the institutions of governance whereas Nehru strengthened them. Also, that while the infrastructure that Modi is building will knit the country closer together, he has divided people communally. Against this, big dams are no longer seen as a great idea, but nor is river linking. And Nehru’s stress on the public sector, while understandable because India’s private sector was small at the time, did not work out well in the end.

By special arrangement with Business Standard

Also Read: Why Coimbatore, Indore & Surat will decide success of India’s urbanisation. Not Mumbai & Delhi