On 17 April 2020, India’s Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade — DPIIT — announced new limitations to existing foreign direct investment rules. It said that any company, located in a country that shares a land border with India, will require government clearance before it can invest in India. These rules will also apply to owners of firms, who are the citizens of such countries, and might benefit from such investments. As a result, companies based out of Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bhutan, Nepal, Myanmar and China will have to abide by these rules.

Also Read: With FDI move, India can now trade with China from a position of strength

China on India’s radar

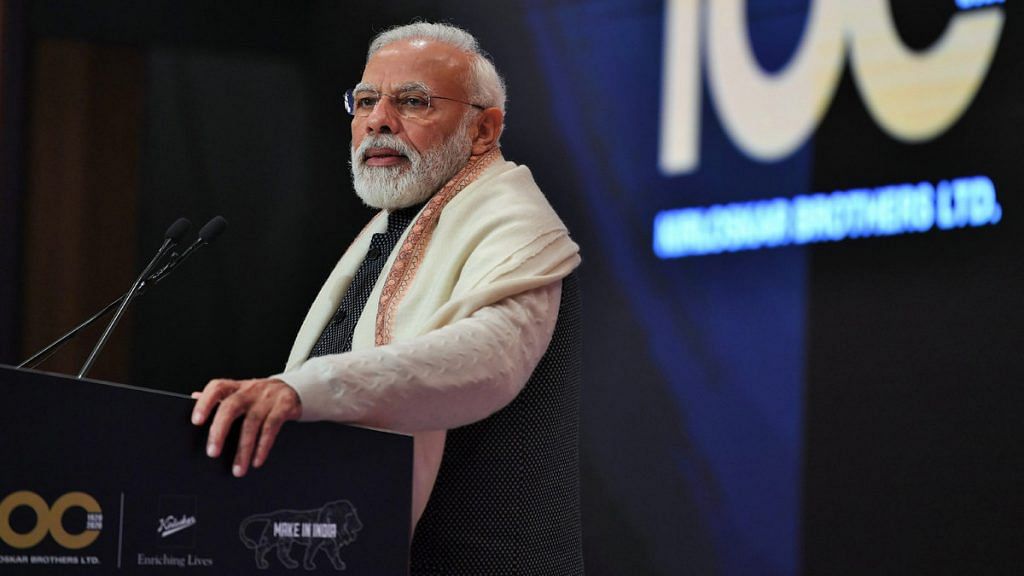

Out of the SAARC countries, these restrictions were already applicable to Pakistan and Bangladesh. Investments by Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Nepal and Bhutan in India were negligible. So, it is quite clear that these revised foreign direct investment (FDI) rules are an expression of the Narendra Modi government’s disappointment towards China, which has mastered the art of exploiting capitalism.

Over the past couple of weeks, authorities in India examined Chinese investments with a microscope. Last week, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) asked custodians to disclose, at extremely short notice, all investments from China. Both the primary and secondary deals were covered. SEBI’s notice came after the People’s Bank of China raised its stake in HDFC Ltd from 0.8 per cent to 1.01 per cent in the March quarter.

Government officials have also indicated that these revised rules will be interpreted broadly and will also apply to Hong Kong, even though its governance and economic systems are separate from mainland China.

The revisions will come into effect once they are notified under the Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA), 1999. In its present form, the DPIIT note does not distinguish between majority/control investments or minority/passive investments from China. It is applicable to all sectors and not just telecommunication, banking, and insurance, which were considered sensitive. The revision to these FDI rules do not require current Chinese investors to apply for government approval. These will be applicable only on their future investments

Other countries too have enacted laws that give governments greater powers to scrutinise FDI inflows. The Australian Government announced that the dollar threshold for FDI screening will be zero (A$0) from the night of 29 March. It has also increased the timeline for processing FDI proposals to six months. On 17 March, the Spanish government enacted a Royal decree amending a 2003 law, which makes it mandatory to obtain prior government authorisation on any FDI proposal. Any investments without such permission will have no legal effect.

Even before the coronavirus pandemic debilitated the Indian economy, authorities had raised concerns about China’s growing influence in it. Ajit Doval, India’s national security adviser, has reportedly flagged concerns over China’s dominance in India’s technology sector. He pointed out worrying possibilities of Beijing’s state-funded apparatus controlling startups here through opaque corporate structures.

Also Read: E-commerce curbs and China FDI rules: Is Covid-19 making India more protectionist?

Impact on tech sector

The revised FDI rules will slow down the pace of Chinese investments in India’s technology-driven businesses. In 2018, these stood at $5.6 billion — a five-fold increase from $668 million in 2016. The Financial Times reported that two-thirds of India’s start-ups, which are valued at more than $1 billion, now have one Chinese venture capital firm as an investor.

However, the revised FDI rules will act as the proverbial speed-breakers that halt the march of Chinese investments in India’s technology. Companies will now have to navigate multiple bureaucratic hurdles and adhere to stricter compliance norms in order to invest in India. The country is in the grip of Covid-19 pandemic and government offices are functioning at a reduced capacity. In such a scenario, nobody quite knows how long it will take for FDI proposals to get approved.

Under the automatic route, companies could invest in India without placing proposals before the government. By introducing these revisions, the government has created one set of rules for certain geographies and another set of rules for its neighbours. In other words, an American company can invest in India without placing its proposals before the government. But a company from China will have to jump through hoops to do the same.

Also Read: China wants India to revise new ‘discriminatory’ FDI policy, says it violates WTO norms

Unanswered questions

The DPIIT note does not distinguish between greenfield and brownfield investments. The former requires a foreign investor to set up a company in India, while the latter involves the purchase of an existing firm or a merger with it. Since the government’s intent is to prevent opportunistic takeovers, this lack of distinction is confusing.

A striking feature of this revision is that all types of investors — private investors (entity or individual), financial institutions, or venture capital funds — will be treated alike. This may create more problems than solve them. For instance, venture capital investments are made by funds registered in offshore jurisdictions with multiple partners worldwide. How will the government determine the nationality of such structures?

Another concern is temporal — while the intention may be to prevent opportunistic takeovers, why do the rules not include a ‘sunset clause’ — the date beyond which the rules will not apply?

Also Read: Govt revises FDI policy over fears of Chinese takeover of Indian firms amid Covid-19 crisis

Need for cogency

The Modi government’s short-term revision of FDI rules, though well-intentioned, may fail to protect India’s long-term strategic interest. To address these concerns in future, India will have to adopt a more cogent approach. It can take a leaf out of the European Union’s book, which passed a regulation to strengthen its foreign investment screening process on the grounds of national security or public order, in 2019. India could also look towards the United States, where the Committee on Foreign Investment screens foreign investments on national security grounds.

In its quest to become an influential global power, India will need investments that help the country import intellectual and technological capital like artificial intelligence, cybersecurity tools, semiconductors and robotics. Therefore, policymakers would be well-advised to create frameworks that factor in India’s long-term strategic interests rather than address short-term emotional impulses.

The authors work at Koan Advisory Group, a technology policy consulting firm. This article is part of ThePrint-Koan Advisory series that analyses emerging policies, laws and regulations in India’s technology sector.

Read all articles in the series here.