India’s merchandise export profile is often described as being overly reliant on the United States. But a closer look at the data signals a more nuanced story. Although the US remains India’s single-largest export destination, it only accounts for about one-fifth of India’s merchandise exports. That means roughly 80 per cent of India’s goods exports continue to go to other markets, keeping India relatively insulated from US tariff shocks.

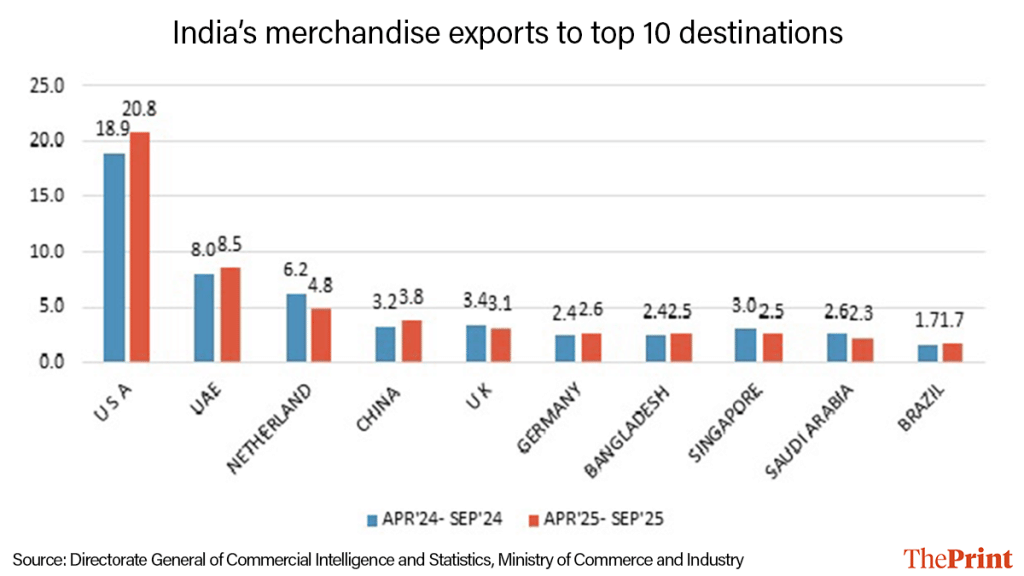

Between April-September 2024 and April-September 2025, the share of exports going to the US rose from 18.9 per cent to 20.8 per cent, helped partly by front-loading ahead of tariff uncertainty (Figure 1). But this does not change the broader pattern: India’s export base remains spread out. The combined share of the top four export destinations declined and remains flat at about 20 per cent, while the share going to other key partners dipped only marginally.

India’s efforts to build trade ties with Africa, Latin America, and ASEAN have yet to yield a significant increase in their shares, and exports to the UK have not picked up meaningfully even after the recently concluded trade agreement, except for textiles. Meanwhile, the UAE has emerged as an increasingly important destination, especially for sectors such as gems and jewellery.

Sectoral breakdown

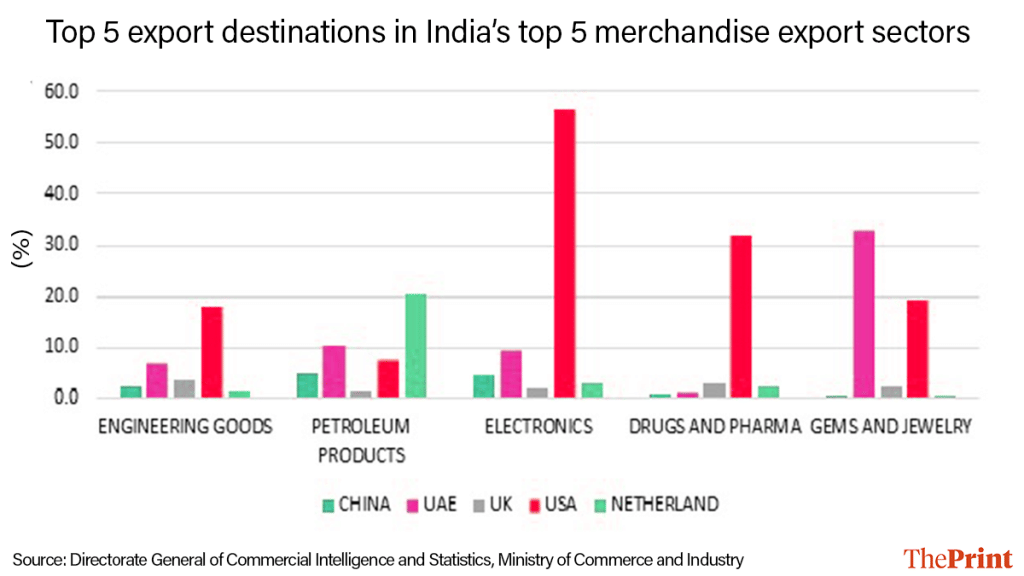

A closer look at sectors reinforces the point. Engineering goods remain India’s largest export category and are spread across markets: the US takes about 18 per cent, while nearly 70 per cent go to destinations other than the top five countries (Figure 2). Petroleum goods follow, as only 8 per cent goes to the US; however, the top third sector — electronics — though being currently exempted from steep tariffs, faces vulnerability as the semiconductor manufacturing accelerates in the US under the 2022 CHIPS ACT.

Pharmaceuticals look less vulnerable to the 100 per cent tariff because almost 90 per cent of India’s exports are generics — not the patented medicines being targeted. In contrast, textiles and marine products, particularly shrimp, remain concentrated in the US and therefore are more exposed.

The standout diversification story comes from gems and jewellery, where the UAE now accounts for nearly a third of India’s exports.

The bottom line: Concentration exists in some sectors, but the system is not excessively dependent on one market.

Where the real vulnerability lies

The story looks very different on the services side — and this is where India faces its biggest exposure.

More than half of India’s services exports go to the United States. Despite services getting expanded beyond IT to include consulting, analytics, design, fintech, professional services, and new AI-linked work, the geographic footprint has not broadened meaningfully.

This concentration now comes with heightened policy risks. The US has raised H-1B visa fees to $10,000 and proposed the HIRE Act, which would impose a 25 per cent outsourcing tax. Both measures would significantly affect India’s services exporters, especially small and medium firms. At the same time, the US is striking selective bilateral deals that prioritise its industrial goals — from critical minerals to high-tech manufacturing — leaving India with limited leverage in negotiations. India’s willingness to discuss sensitive areas like agriculture and dairy simply to keep talks moving underscores this imbalance.

India’s long-term trade success hinges far more on services than on goods. The services surplus has consistently stabilised India’s external sector, and services are the country’s most competitive and globally integrated export engine.

Yet India’s trade agreements remain disproportionately goods-centric. India’s services-focused CEPA strategy must prioritise smoother mobility for skilled workers, mutual recognition of professional qualifications. It should also support MSME services exporters—including design, animation, and legal-tech firms—while promoting interoperability of digital systems, an area where India can leverage its strong digital public infrastructure.

Also read: That one sentence from US central bank changed gold prices

A shift is underway

To reduce its reliance on the US market, India has been expanding its trade diplomacy. After the Gulf Cooperation Council bloc-wide deal stalled, India signed a CEPA with the UAE and is negotiating with Qatar, with Saudi Arabia likely to follow. Negotiations with the European Union, the Eurasian Economic Union, and Latin American partners such as Chile and Peru are also in progress. These moves represent an important shift toward broader economic partnerships.

India’s merchandise exports are diversified enough to weather tariff shocks and global uncertainty. But India’s most reliable, high-growth export engine — services — rests on a narrower base and faces growing policy risks.

If India wants to build lasting leverage in a turbulent world, it must put services at the centre of its trade strategy. A dedicated Services CEPA Strategy is not just desirable — it is essential for India’s long-term resilience and influence in the global economy.

The author is an assistant professor at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi. Views are personal.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)

It would have been nicer if the author had also talked of India’s textile and apparel sector, which is among those hit hardest by the 50% tariff imposed by the United States on Indian goods, effective August 27. The US is the single-largest market for India’s textile and apparel items, with around 28% of these Indian goods being sold in the world’s No. 1 economy. India’s textile and apparel exports to the US in the financial year 2024-25 stood at nearly $11 billion.