Earlier this week, the Union government notified India’s next population census, which will include a caste census: the first time caste-based data will be collected since the 1931 Census. This enumeration of castes will have momentous political consequences. The fact that it is being conducted reveals much about India’s political climate and how the state sees its obligations to its citizens.

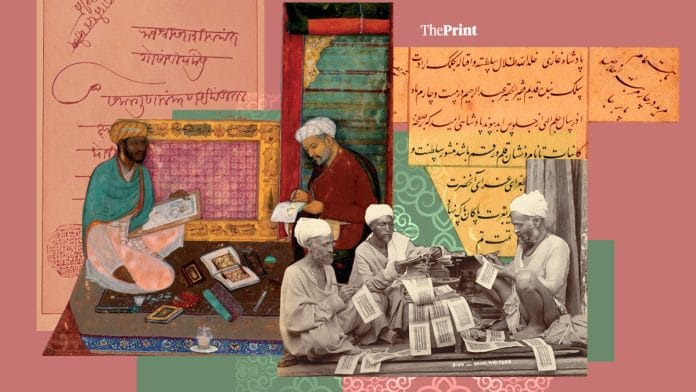

Throughout history, data collection has been the means by which rulers understood the people they governed. But the methods, depth, and objectives of censuses have evolved over the centuries: from alliance-building under medieval kingdoms such as the Cholas, to balancing caste and economic dynamics under the Mughals, Rajputs, and Marathas, to racist ethnography and ideological control under the British Raj.

The history of Indian caste censuses is, in many ways, the history of Indian statecraft.

Revenue, rights, and caste in ancient India

From the beginnings of Indian statecraft in the Arthashastra (3rd century BCE – 3rd century CE), rulers and political theorists emphasised both revenues and caste order as important to an orderly kingdom. In Book 2, Chapter 35, the text’s authors laid out the duties of revenue officers, who had to record cultivated lands, exemptions, and grants, and to list households “of the four social classes.” Of course, the quality of such data couldn’t be taken for granted, so secret agents were to verify all information. The state described in the Arthashastra derived revenue not just from industry and agriculture, but also from fines imposed on offenders. In Book 3, fines and punishments were listed according to caste, upholding the social hierarchy envisioned by Brahminical texts.

We have no idea to what extent early Indian states actually implemented the Arthashastra, but inscriptions from the early centuries CE suggest another reason rulers might have wanted to keep an eye on castes. Groups such as bankers, merchants, weavers, scribes and artisans in the Gangetic plains were forming caste-like collectives and participating in city administration. As historian Chitrarekha Gupta writes in ‘The Writers’ Class of Ancient India’, such collectives were a significant political and social force. Throughout the medieval period, between roughly 600 and 1100 CE, they developed across the subcontinent. States had to deal with city assemblies, village assemblies, occupational assemblies, and caste assemblies—all with their own laws, traditions, and claims to rights.

The Chola empire, the most centralised early medieval state, ordered multiple land surveys to fix tax rates, but occasionally ran into headwinds from organised assemblies of cultivators and landowners. In the early 11th century, when the empire was on the ascendant, this wasn’t too much of a problem. In fact, land surveys helped the Cholas build alliances with communities by ensuring that temple endowments were recorded and maintained. But by the late 11th century, as the tide of conquest slowed and the court weakened, inscriptions show that “super assemblies” like the Chittirameli-Periyanadu alliance—composed of cultivators, landlords, and Brahmins—began to make their own decisions on what revenues to pay the state. By the 1300s, such alliances were also asserting authority over social and political hierarchies and lobbying for rights and privileges. For any medieval Indian ruler, measuring land and monitoring caste were absolutely essential.

Also read: Explainer: Caste Census – history, politics, and its significance today

Mughals, Marathas, and limits of caste data

While few revenue records survive from the early medieval period, the picture improves drastically from the 1500s, as new gunpowder states, like the Mughal empire, invested in larger bureaucracies. We have a fairly good picture of Mughal administration from the Ā’īn-i-Akbarī (“The Institutions of Akbar”), written by the courtier Abu’l Fazl. He recorded estimated revenues from districts, apparently based on measurements taken by local bureaucrats. Interestingly, he also paid attention to North India’s many castes, making note of Thakurs, Rajputs, Jats, and other landowning communities.

However, while the Mughal bureaucracy produced mountains of statistics, the data quality was extremely dubious. In ‘Rethinking the Economy of the Mughal Empire’, historian Sumit Guha critically examined Mughal revenue documents. He found that assessed tax revenues were infrequently updated: after all, accurately estimating harvests would have required bureaucrats to revisit villages across seasons and years—something they simply did not have the resources or inclination for. Akbar’s successor, Jahangir, cited the same revenue statistics in his memoirs as those in the Ā’īn-i-Akbarī—by then, 20–30 years outdated.

Mughal bureaucrats also fabricated revenue estimates for restive or unconquered provinces to make political claims. Where they did have control, they demanded extortionate shares of the harvest, between a quarter and a third. In Beyond Caste: Identity and Power in South Asia, Guha also points out that some caste data were recorded at the village level, so that revenue demands could be made on caste headmen. Unsurprisingly, village scribes often fudged numbers to avoid taxes; local zamindars bribed officials; and officials fabricated data to seem competent. If caught by inspectors, brutal punishments were inflicted. But since Mughal officials didn’t have accurate revenue estimates in the first place, they sometimes flogged or imprisoned scribes, collectors, and village heads who—for justifiable reasons—couldn’t meet their expectations.

Guha writes: “…not only corrupt officials but also merchants, bankers, and, indeed, small farmers striving to avoid starvation had every incentive to conceal information… [Data] were generated out of a constant struggle between peasants, local chiefs and officials…. a torrent of unrecorded bribes and a wealth of recorded [inaccurate] statistics were the result.” Corruption became embedded at every level of the state; European travellers frequently complained about the bribes demanded by Mughal officials.

Yet there was something to be said about the underlying idea: of detailed local data, responsive to different communities and conditions. To tackle this problem, writes Guha, when Maratha king Shivaji defeated the Mughals and established rule in the Deccan from 1656 onwards, he reprimanded corrupt officers, appointed new village accountants, and ordered accurate revenue settlements. Other Indian states also sensed the need for better data. In ‘Cents, Sense, Census: Human Inventories in Late Precolonial and Early Colonial India’, historian Norbert Peabody examined the Marwar ra Parganam ri Vigat, a survey of the Marwar kingdom between 1658–64 by Munhata Nainsi, an Oswal merchant and minister to Maharaja Jaswant Singh Rathor.

Nainsi’s survey, a khanasumari, enumerated households by caste in every district capital: perhaps the first true ‘caste census’ in India. Other kingdoms in Rajasthan conducted similar khanasumaris and village surveys called yaddastis; but the concept of aggregating rural and urban data did not develop. While Nainsi privileged his own Oswal community in his listings, he otherwise acknowledged that each locality had distinct caste hierarchies. Nor was he overly preoccupied with religion. That, however, was soon to change.

Also read: The Centre must use the caste census

The British takeover—colonial caste surveys

By the 18th century, writes Guha (Beyond Caste), many Indian states—especially in Maratha dominions—had developed fairly detailed caste enumerations (by households), used to regulate social hierarchies and impose differential taxation and privileges. Populations remained relatively mobile, responding to incentives offered by competing states. Into this bewilderingly complex system came the British, with their own (mostly imagined) ideas of how Indian society functioned, along with a hard-headed approach to revenue.

The British, somewhat justifiably suspicious of locally reported data, sent salaried officials to conduct their own surveys. Unlike Indian states, writes Guha, the British counted individuals, not households. They also insisted on permanent addresses and borders, as they were suspicious of migration. This devastated itinerant traders, such as the Banjaras, as well as pastoralist communities. Perhaps most damagingly, the British imposed their own categories and political needs on India’s shifting mosaic of identities.

In 1845–46, after battling insurgents from forest tribes, the Bombay government insisted on categorising people by religion rather than caste and separately identifying “Wild Tribes.” After the 1857 rebellion, the British grew even more obsessed with religious categorisation. Following Queen Victoria’s proclamation that the Raj would not interfere with Indian customs, the British consulted upper-caste Indian elites—primarily Brahmins—to define those customs. The results were deeply skewed.

As historian Nicholas Dirks notes in Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the Making of Modern India, HH Risley, who oversaw the 1901 Bengal Census, relied extensively on scriptures such as the Manusmriti, which most castes didn’t actually follow. Risley also bought entirely into racial theories linking caste to ‘Aryan’ descent, and endorsed upper-caste norms, such as child marriage and the prohibition of widow remarriage, that Hindu reformers were fighting against. He used this racially weaponised data to argue for the Partition of Bengal and for separate electorates for Hindus and Muslims.

Indian elites quickly adopted these British categories, since they appeared ‘scientific’ by the standards of the time. There was as yet little understanding of how misshapen colonial theories about India were. Racial theories and binary religious identities—Hindu and Muslim—were absorbed wholesale. Caste organisations flourished, connected by railways and the telegraph. Hindu and Muslim elites found that they had much to gain from consolidating a once-diverse kaleidoscope of caste groups along religious lines. The eventual demand for Partition was the culmination of decades of identity formation built on data collected by a self-interested colonial empire.

Since Independence, generations of Indian statisticians and sociologists have drastically improved the quality of data collection, allowing for much more humane policies and planning. But history shows that good data isn’t guaranteed—nor are good intentions or good policy outcomes. Indian rulers have always recognised that data is power.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of ‘Lords of Earth and Sea: A History of the Chola Empire’ and the award-winning ‘Lords of the Deccan’. He hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti and is on Instagram @anirbuddha.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Prashant)