In his blog, Swaminomics, in The Times of India, Swaminathan S Anklesaria Aiyar admonishes those who look back at India’s pre-Islamic past as a golden economic period, asserting instead that India was actually much poorer than other countries on a per capita basis and that we should look to the next few decades as the real golden period in India. In making his arguments, he cites statistics from the famous work by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development economist Angus Maddison, Contours of the World Economy 1–2030 AD: Essays in Macro Economic History.

Below are the key points made by Aiyar

- As of 1 CE, India’s per capita income was half that of Italy and even slightly lower than the world average (32 per cent of the world’s GDP vs 33.2 per cent of its population)

- India’s GDP and per capita income stagnated from 1 CE to 1000 CE at $33.75 billion and $450 per annum, respectively

- Under Muslim rule between 1000 and 1700 CE, GDP tripled to almost $90.7 billion, while per capita income improved slightly to $550 per annum

- During the British period between 1700 and 1950, annual GDP rose to $222.2 billion and per capita income to $619

Aiyar cites these numbers to conclude that it was the Hindu period that was one of stagnation while both Islamic and British colonial periods were eras of relative growth and that both these eras were left in the dust by our growth since Independence. India actually wasn’t made poorer by the British, it was left behind by the pace of European growth driven by the industrial revolution.

While Europe certainly benefited greatly from the industrial revolution, Aiyar misleads readers about India’s history by selectively citing statistics without relevant context. In my view, the flaw in Aiyar’s thesis is that he is simply comparing India over millennia with little to no global context. When compared over 2000 years, and in blocks of several centuries, any country will tend to get better with time, in terms of mortality rates and economic performance as civilisation in general advances. A more reasonable analysis requires a comparison against other countries during each time period. I focus my analysis on per capita GDP since that is what Aiyar uses. My source is the same as Aiyar, specifically Table A.7 titled “World per Capita GDP: 20 Countries and Regional Averages, 1–2003AD (1990 international $)”. Let us take each of Aiyar’s assertions in turn.

Also Read: ‘Indians never invaded’ is a myth. Guptas, Cholas, Lalitaditya Muktapida were conquerors

Assessing the Hindu period

In the year 1 CE, India’s per capita income was $450 while Italy’s was indeed almost double at $809. What Aiyar leaves out is context. Most of Western Europe, and virtually all of the rest of the world, is actually in the $400-450 range (France and Spain are slightly higher at $473 and $498, and the world average was $467). The whole world was broadly equal in terms of per capita income. Italy, the example Aiyar chooses, was an exception. Why was that? Italy, in 1 CE, was the centre of a massive empire that drained resources from vast regions, including parts of Western Europe, the Balkans, Eastern Europe, the Middle East and much of North Africa from Egypt to Morocco. India thankfully was never a colonising nation. Notice what happened to Italy by 1000 CE. After the Roman Empire collapsed, it declined right down to $450, exactly where India stood in 1000 CE, again conveniently omitted by Aiyar.

As for his second claim, Aiyar pooh-poohs India’s history by citing that per capita income stagnated for 1000 years during the Hindu-ruled period. What Aiyar leaves out is that European per capita GDP declined by a whopping 29 per cent during this millennium. In comparison, India and China, which remained flat, outperformed Europe dramatically. The only part of the world to show some increase in per capita GDP during this millennium is West Asia by about 19 per cent, because of Islamic colonial loot that accumulated in this region starting in the 7th century (including from the Northwestern parts of India).

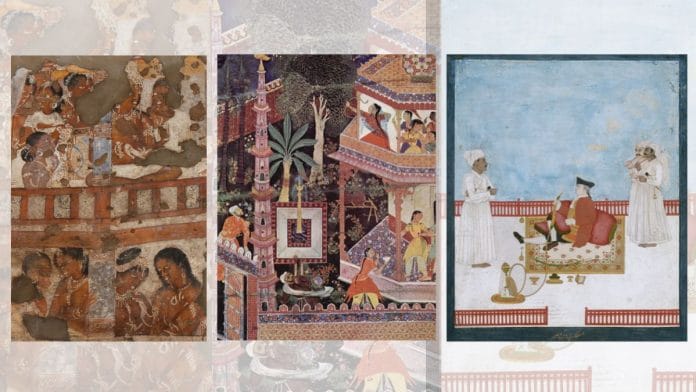

Summing up the Hindu period, it is true that India did not have a per capita income that was enormously higher than other countries. But that is not what was implied by “sone ki chidiya” or golden bird. India back then was the land that exported luxury goods — spices, ivory, pearls, perfumes and high-quality textiles — highly sought-after across the world. India wanted to be paid only in gold. In 77 CE, Pliny the Elder, a Roman senator complained that the fondness of Roman women for luxury goods from India and called India “the sink of the world’s gold”. Hence the phrase “sone ki chidiya”. It was first coined by Romans with later references in the Arabian Nights as well. Gold was also seen as auspicious in Hindu culture. Prosperity is always relative, and when the country with the world’s largest GDP (India) also remains flat over a millennium during which Europe declined by 29 per cent, “sone ki chidiya” does assume a larger meaning.

In addition, we are all well aware of the massive temples built by the Cholas in the south (temples in the North largely did not survive Islamic conquests) as well as international universities such as Takshashila, Nalanda, Vikramashila, Odantapuri etc that flourished in North India and attracted students from numerous countries. India led the world at that time in math and science as well. These are clear evidence of the nature and economic might of Indian society during the first millennium. Historian AL Basham’s book The Wonder That Was India, chronicles this period of history.

Also Read: Some Hindus even praised Khilji in Sanskrit texts — Medieval India’s complex power games

Assessing the Muslim period

Aiyar’s third claim is that India performed better during the Muslim period than during the Hindu one, since per capita income grew by 22 per cent to $550 by 1700 CE from $450 in 1000 CE. Again, the relevant comparison is how other countries performed during this period. Since this is just before the Industrial Revolution, one can compare it with Europe as well. During this period, western Europe went from $427 to $997, a 2.5-time jump in per capita income. China saw a 33% increase from $450 to $600. The US saw a similar 32 per cent increase from $400 to $527. Mexico, too, did better, with a 42% increase from $400 to $568. Indeed, India has among the worst growth records in the world during this period, with the global average increasing 37 per cent from $450 to $616. So much for India doing better under Muslim rule. In fact, it is telling that we don’t hear of a single major university being established during the Islamic period.

But we hear stories about the enormous wealth of the Mughal courts. Wasn’t India rich? The Mughal court was indeed enormously wealthy, but that was just the court and the nobility, not the country. While one cannot identify every factor that affected economic outcomes back then, the underperformance in per capita GDP noted above is further magnified by the extreme concentration of wealth and resources with the kings and nobility. Starting with the conquest of Sindh in the early 8th century by the Umayyad caliphate and through the Delhi Sultanate period upto the mid-16th century, Muslim-occupied parts of India, untold riches and countless slaves were given as tribute to the capitals of various Islamic caliphates in the Middle East or Central Asia or to the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina, writes MA Khan in Islamic Jihad: A Legacy of Forced Conversion, Imperialism and Slavery.

While the Mughals were large enough to declare independence from foreign empires, vast transfers of wealth continued in the form of hiring nobles from abroad (over 70 per cent of nobles in the court were from the middle east or central Asia, even during Akbar’s time), gifts to foreign kings and lavishly sponsored Haj trips for thousands annually. In contrast to Hindu rulers who taxed farmers around 16 per cent of production, the Mughal tax rate was 30-50 per cent, wrote Irfan Habib in his book The Agrarian System of Mughal India, 1556–1707. The lion’s share of which went to just a few hundred nobles in the kingdom while the populace lived in penury.

Francois Bernier, who visited India during Aurangzeb’s reign, writes in his book Travels in the Mogul Empire (1658-70), that it is “a tyranny often so excessive as to deprive the peasant and artisan of the necessaries of life, and leave them to die of misery and exhaustion”, that “…in Delhi for two or three who wear decent apparel, there [are] seven or eight poor, ragged and miserable beings”. One shudders to think about rural India. He continues: “It is owing to this miserable system of government that most towns in Hindoustan are made up of earth, mud, and other wretched materials; that there is no city or town which, if it be not already ruined and deserted, does not bear evident marks of approaching decay.” That explains the performance of India’s GDP during the Mughal period, which was a reign by and for a few Muslim nobles over vast destitute masses.

Also Read: Turks weren’t barbarians. They appreciated Hindu temple architecture

Assessing the British period

According to Aiyar, Indian GDP and population growth “intensified in the British period”, though he admits per capita income increased “only marginally” to $619 by 1950, a 12 per cent increase over 250 years. This is spin par excellence. Any “intensification” has to be seen in the global context. During this period, western Europe went from $997 to $4,578, a five-time increase, and the US from $527 to $9,561, or about 20 times. But let us exclude these as benefiting from colonial plunder and the Industrial Revolution.

Even the colonised world left India vastly behind. Eastern Europe and the USSR more than tripled their per capita GDP from around $600 to more than $2,000, and all of Latin America from $527 to $2,503, a 5-time growth. West Asia tripled from $591 to $1,776. Africa doubled from $421 to $890. That puts India’s 12 per cent increase, and the magnitude of the British loot of India, into context.

Aiyar’s overall thesis is that GDP and per capita income stagnated, along with population, during Hindu rule. During the Islamic and British periods, GDP grew but the population also grew rapidly, causing per capita growth to grow by much less than the GDP, though still better than the Hindu period.

I have shown above that in terms of per capita GDP, India (and China) outperformed the world during the Hindu period and lagged badly in the Islamic and especially British periods. Could that be solely driven by India’s population trends? Not at all. In fact, table A.2 in the Maddison report shows the opposite.

During 1-1000 CE, India showed zero population growth (Europe and China were also zero) while the world average was 0.02 per cent. So India’s superior per capita performance did not owe to falling population or to the rest of the world growing much faster in population. During the Islamic and British periods, India’s population growth has actually been lower than the world average (and the key regions being compared). During 1000-1500 India, Western Europe, China and the World grew at 0.08 per cent, 0.16 per cent, 0.11 per cent and 0.10 per cent, respectively. For 1500-1820, those numbers stand at 0.2 per cent, 0.26 per cent, 0.41 per cent and 0.27 per cent, respectively. Maddison provides population growth for smaller blocks of time after this but the message is the same. Other regions saw faster per capita income growth despite higher population growth rates.

One can be legitimately dismayed that a commentator of Aiyar’s stature would choose to imply that India did better under the Muslim and British periods than during the Hindu period. It is fine to decry political violence or to politically oppose the current Indian government. But it is certainly sad that he is taking to disparaging India’s Hindu past.

While Aiyar is right in stating that “India’s golden era is now”, the country’s per capita income is likely to remain well below today’s rich nations even after 20-30 years. India has a long way to go before it achieves the pre-eminent position of the first millennium.

Swaminathan Venkataraman is a graduate of IIT Madras and IIM Calcutta. He works as a financial analyst in New York and serves on the board of the Hindu American Foundation. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)