It’ll be unfortunate if India’s next steel king is decided not on the wrestling mat — but via walkovers.

Want to screw up a good law? Just try to make it a great one.

That’s what India did last November when it added a number of restrictions on who could bid for assets in a bankruptcy. The idea of the new regulations was to make it hard for errant owners to regain control of businesses without first settling their dues.

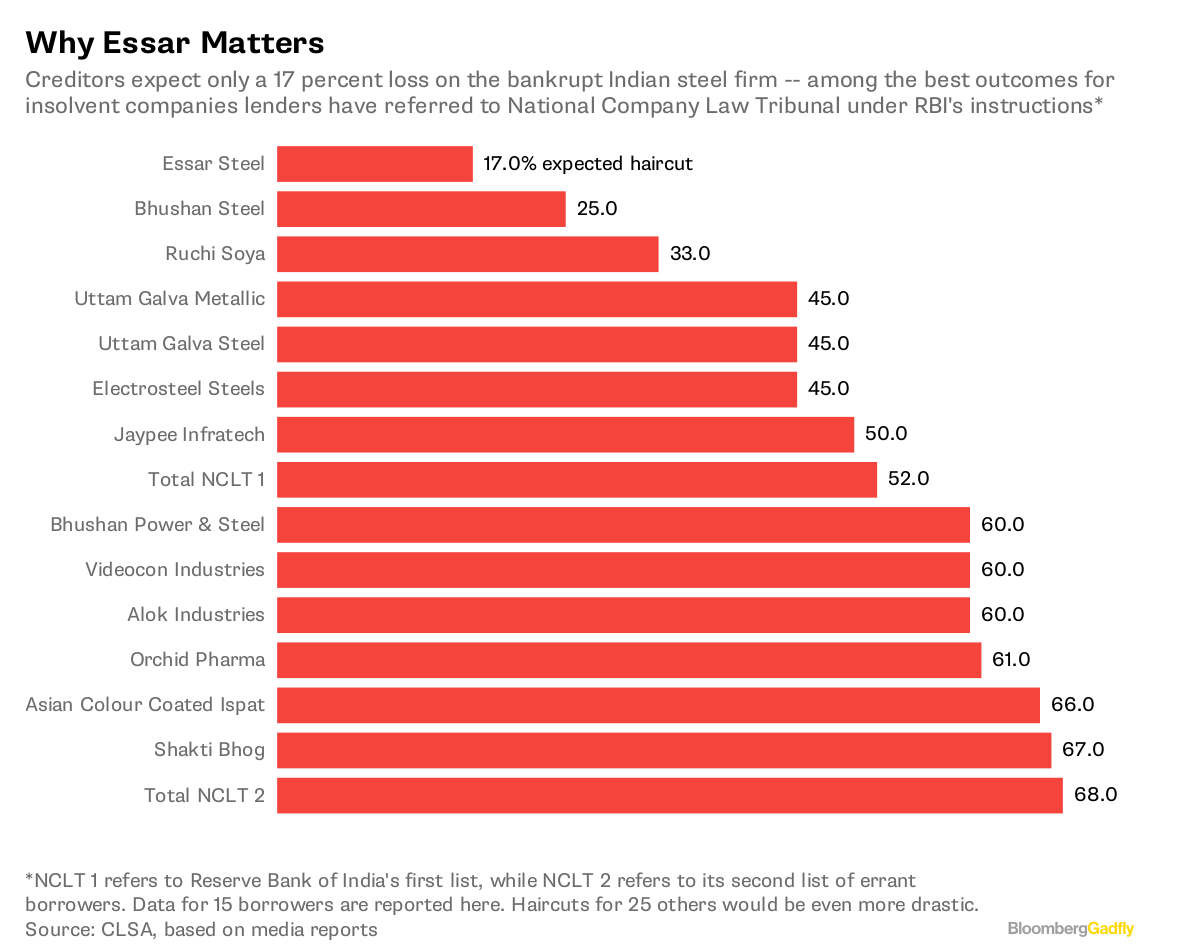

But the morality was legal overkill; and that’s now evident in the farce that the insolvency of Essar Steel India Ltd. has become.

Rather than helping creditors with the best possible recovery for the $8 billion that’s trapped in a 10-million-tons-a-year metals business, the bidding war has disintegrated into a contest to prove rivals ineligible. It’ll be unfortunate if India’s next steel king is decided not on the wrestling mat — but via walkovers.

Rival investor groups led by VTB Capital and ArcelorMittal were the two contestants in the first round. But the creditors’ committee deemed both buyers to be ineligible, and went for a second round of bids. However, in a surprising twist, the National Company Law Tribunal on Thursday held the second round, in which Vedanta Group and JSW Steel Ltd. had also jumped into the fray, to be invalid. Creditors now have to reconsider the VTB and ArcelorMittal proposals.

Blame the confusion — and crucial time wasted in litigation — on 29A. The section, which the government slipped into the bankruptcy code in November, introduced four layers of ineligibility for potential bidders. That’s a delight for losing sides’ lawyers trying to trip up the winner, but a frustrating outcome for lenders whose only wish is for a big check quickly from a new owner who knows the steel business.

Now that they’re back to reconsidering the original offers, creditors will have to cast a fresh glance at the VTB bid, which is problematic for two reasons. One, the consortium has a minority participation by the billionaire Ruia family, the original controlling shareholder of Essar. Preventing previous owners from making last-ditch attempts to hold on to their prized assets was supposedly the main intention of the government in introducing 29A.

Ruia’s bidding buddy also comes with its own baggage. There’s no convincing answer as to how a unit of VTB Bank PJSC, a Russian lender whose chairman made it to a U.S. sanctions list this month for worldwide malign activity, could be considered fit to own a major Indian steel business.

So what has Section 29A really achieved? Well, for one thing, it’s become an instrument of virtue signalling. Take Indian steel tycoon Sajjan Jindal’s JSW, which stepped in as VTB’s second-round partner, replacing the Ruias, just in case the latter were deemed unfit. Rather than telling creditors what they could do for Essar that the other party couldn’t, Jindal and ArcelorMittal had a public showdown about their relative piety.

Whether ArcelorMittal’s sale of shares in another nonperforming asset has cured it of ineligibility to bid for Indian stressed assets, or whether Jindal’s sister’s previous involvement in another bankrupt steel firm makes him less than pure somehow, ought to be irrelevant to resolving Essar’s insolvency.

Yet these were precisely the points in a Twitter fight between Jindal and ArcelorMittal. It would provide some comic relief from India’s $200 billion bad-loan problem… if New Delhi’s bankruptcy law didn’t turn the tragedy into such a farce.

The 270-day deadline for resolving Essar’s insolvency is set to expire at the end of the month. The tribunal judges on Thursday added another month to the process to compensate for time lost in litigation.

That’s of little consolation to creditors. India’s banks have waited for more than a decade for a modern bankruptcy code. Now that it’s finally there, an overdose of morality is crippling it.

Essar looks like it’s headed for a lengthy day in the courts; in smaller bankruptcies, where there isn’t much value left, the lenders aren’t even bothering to accept offers lest government agencies accuse them of corruption later. Those businesses, like ABG Shipyard Ltd., may be heading for liquidation. An unnecessary culling in a country that doesn’t have enough jobs for its young workforce, and all in the name of purity. —Bloomberg Gadfly

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.