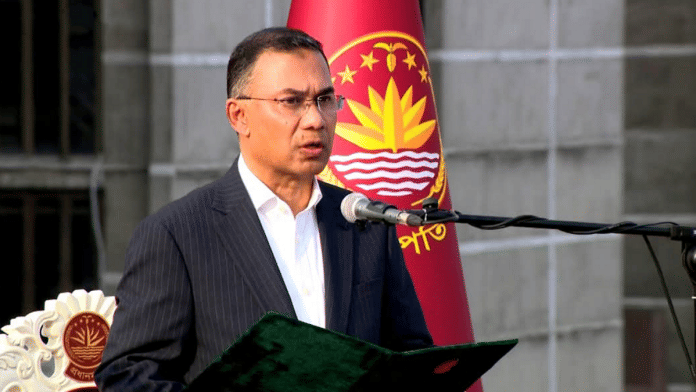

The newly elected Prime Minister of Bangladesh, Tarique Rahman, is only the second elected and empowered male to assume this office in the country’s history. The first was the nation’s founder, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. All other male prime ministers or chief advisors either served military strongmen or led caretaker governments. One of them—Rahman’s immediate predecessor—held the dubious distinction of being an interloper who was parachuted into office by exigent circumstances. If Rahman’s ascent to Prime Ministership has been arduous, having spent nearly 17 years in exile in the United Kingdom, his term in office is not going to be less challenging. He inherits a Bangladesh buffeted by great power rivalry, regional rivalries, an ailing economy, and a troubled political environment. Add to this the threat of radical Islamists trying to hold the new government hostage to their pernicious agenda. Clearly, Rahman has his task cut out for him.

The people of Bangladesh have delivered a clear verdict in favour of his party, handing it a two-thirds majority in the Jatiya Sangsad (JS), which should work as a shot in the arm. Yet this overwhelming mandate also brings with it heightened expectations of good governance and economic prosperity. Rahman cannot make any excuse about being hobbled by a coalition or lacking the legislative strength to adopt the reforms required to bring political stability and economic growth.

Before the elections, many political pundits made the assessment that while the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) was best placed to win the most seats, there were doubts about it getting a simple majority in the JS. One reason for this was the strong performance by the Jamaat Islami (JI) in opinion surveys, closing the gap with the BNP. The spectre of a hung parliament or a government with a slender, simple majority, or worse, a Jamaat Islami-led government was hanging over Bangladesh’s political firmament.

A coalition or even a slender majority would seriously constrain the BNP from undertaking bold initiatives and reforms. There was also an apprehension that the Islamist alliance led by JI could emerge in pole position. Add to this the looming uncertainty surrounding the “July Charter” (which some wags call the Jamaat Charter) planted by the Mohammad Yunus regime. It was clear that Rahman or whoever else cobbled together a majority would be hamstrung in running the country. A two-thirds majority has, however, carved out adequate political space for Rahman and his party to break the shackles that Yunus and his backers tried to impose on future governments in Bangladesh. The referendum and its more egregious and objectionable clauses will no longer be a limiting factor for the new government.

But despite receiving a resounding mandate, Rahman will face strong opposition, especially from the resurgent JI. With nearly a third of the popular vote, the Jamaat has moved from the margins of Bangladeshi politics onto the centre stage. As the principal Opposition party, the JI will seek to expand its political space. Not only will its presence in the parliament give it the platform to push its agenda, but it will also use its street power to exert pressure on the government. The JI’s capacity to influence institutions—educational, legal, media, military and bureaucracy—will be enhanced by its political and street power, potentially expanding itsinfluence greater than what it has been able to exercise so far. Although the BNP has the numbers not to be marginalised by the Islamists, it will nevertheless come under a lot of pressure because of the populist positions that the Jamaat and its allies will take on India, on Islam/Shariah, on economic issues, and on minorities.

Faced with the political pressure from the Islamist radicals and right-wing forces, Rahman could take one of two paths. He can take the path of least resistance and appease the Jamaat. He could also try to appropriate Jamaat’s agenda—for instance, taking a strident stand against India to burnish his nationalist credentials with an Islamist tadka (tempering). But such as apolitical strategy could easily backfire because the odds of it playing on the Jamaat’s pitch and winning are stacked against the BNP. In the absence of the Awami League (AL), the Jamaat occupies the opposition space and will be seeking to expand its political base. Rahman cannot afford to cede any space to the Islamists, as any such concession will come at the expense of the BNP.

He can never be more Islamic than the Jamaat or any of the other Islamist organisations; nor can he outdo the Islamists in anti-India rhetoric. Moreover, embracing the anti-India sentiment could be a double whammy: continued hostility with the Jamaat and strained relations with India. In other words, Rahman will ultimately have to confront the Jamaat and cut it to size, for his own political survival. A friendly or even normal relationship with India will only help, not harm him. If Rahman were to do some out-of-the-box strategising, he would realise that the smart thing to do would be to allow AL space to function as an opposition party, if for no other reason than to restrict the space of Islamists and JI.

While the domestic front will be challenging, on the international front too, Rahman will have to tread carefully, keeping in mind the economic, security, and political vulnerabilities of his country. The world and the regional dynamics have changed in the two decades that BNP has been out of power. Tarique himself would have changed. The expectation is that the moniker ‘Dark Prince’ he had earned when his mother, Khaleda Zia, was Prime Minister in the early 2000’s no longer describes him. He appears to have matured and become more sober, reflective and contemplative, and will not be prone to reckless actions that gave him notoriety 20years ago. The new realities confronting him can only be ignored at his and his country’s peril. It was one thing for an unelected and temporary Yunus regime to flirt with dangerous ideas and elements, quite another for an elected and responsible government to do the same.

Bangladesh will have to walk the tight rope between China and the US. If events of the last couple of years and the allegations, or “conspiracy theories” swirling around are anything to go by, the US is no longer ready to allow China to expand its footprint in Bangladesh. Statements by US officials and leaks in the American media make clear that Rahmanwill have to ensure he doesn’t allow Bangladesh to become China’s playground. The fact that the Americans are ready to do business with radical Islamists like Jamaat should ring alarm bells in BNP circles. If anything, this is a clear signal to the new government that the Americans will not hesitate to engage with the Jamaat should BNP do anything against American interests. Perhaps the American thinking is back in the 1970s, when they saw the Islamists as allies to counter the communists and nationalists. How Rahman approaches the American demands will hold consequences for Bangladesh’s economy. The Trump administration is ever ready to weaponise its financial and trade clout to achieve strategic objectives.

On the India front, too, Rahman cannot afford to adopt a cavalier approach. Both Bangladesh and India will have to work together to repair the damage done during the Yunus administration. The BNP government will also need to dial down some of the rhetoric regarding India. It is one thing to do electoral grandstanding and announce a review, even cancellation, of all the agreements with India, and quite another to reverse them once in government. Many commercial and investment deals would have in-built safeguards, including arbitration clauses, making abrupt withdrawal both costly and complicated. Rahman will also realise that the economic linkages developed by the Hasina administration with India were mutually beneficial. Severing them will not be easy. Bangladesh needs good relations with India to develop, just as India needs a close relationship with Bangladesh because of the security, economic and connectivity benefits that come India’s way. To be sure, neither side will get all it wants. There will always be issues on which there will be differences. Even under Hasina, there were issues of friction—river waters, political (CAA law), state of minorities, legal (extradition), economic, connectivity, security, trade terms— but both sides managed the bilateral relationship by finding workarounds and kept moving forward.

There has been considerable speculationabout how the BNP will balance relations between India and Pakistan. Clearly, much of this is overstated. Any objective analysis of Bangladesh’s relations and interests will make clear that there is no comparison between what India brings to the table and what Pakistan offers. If “balancing” means that Bangladesh will engage Pakistan more than what prevailed under the AL government, it is something India can live with. But if this engagement is a way to signal hostility toward India and cross established security red lines, either by allowing links with insurgents in India’s Northeast or by turning a blind eye to Islamist terror organisations’ activities in India, then it will invite a severe response. Prime Minister Modi made it clear in 2025 that the new Indian security doctrine announced after Operation Sindoor is not limited to Pakistan.

Given the circumstances under which the elections took place in Bangladesh, the results thrown up are the most favourable that India could have expected. These are good for Bangladesh because they hold the promise of political stability and certainty, and they are good for India, which has a credible partner to work with. There are no naïve expectations in India of a return to halcyon days in bilateral ties. There is also no blind trust or any letting down of the guard. But there is cautious optimism on a decent working relationship, which could smooth out many of the rough edges that crept into the relationship over the last couple of years. A lot will, however, depend on how Rahmanplays his cards. If he doesn’t do anything to hurt India’s security interests and rein in the open season declared on minorities by the Yunus regime, both India and Bangladesh will move forward. If not, then there will be turbulent days ahead.

Sushant Sareen is a Senior Fellow at Observer Research Foundation.

This article was originally published on the Observer Research Foundation website.