A curious shift has been occurring within India’s trade data. Despite the nation celebrating unprecedented foodgrain harvests and increased horticultural production, the latest official figures from the Directorate General of Commercial Intelligence and Statistics indicate that agricultural and allied imports have increased over two consecutive years, rising from $52.67 billion in 2022-23 to $62.52 billion in 2024-25.

In contrast, exports have remained relatively stagnant. As a result, there is a diminishing net surplus in a sector where India should be strengthening its global competitive advantage. The concern is not that India is increasingly reliant on imports across all sectors — some strategic imports will invariably be economically justified — but rather that the trade deficit is tightening specifically in commodities where domestic production capacity exists but remains underutilised. This discrepancy between potential and actual performance encapsulates the core of India’s agricultural paradox, with the data presenting a compelling narrative.

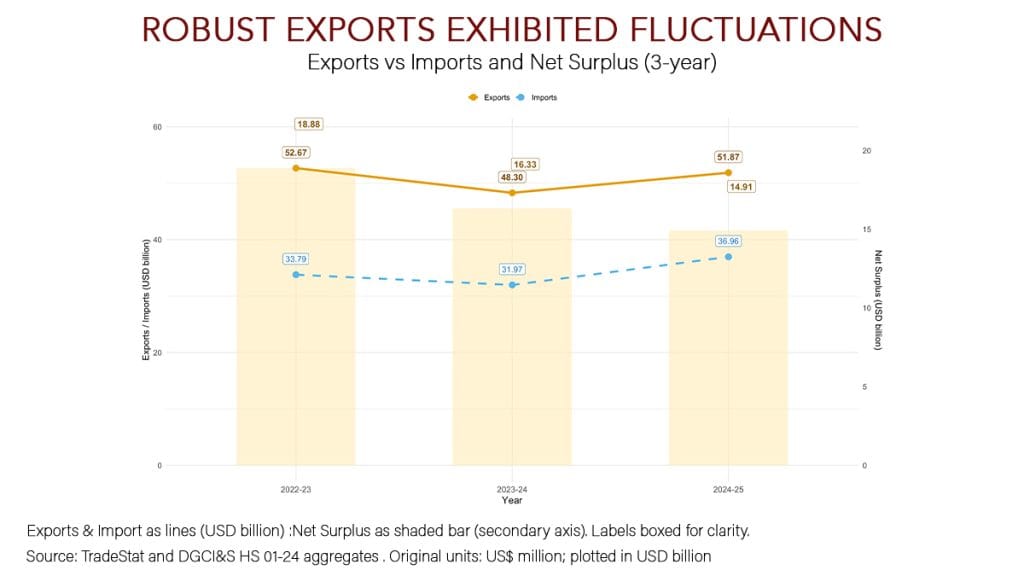

The chart illustrates that while exports have remained robust, they have exhibited fluctuations: approximately $52.67 billion in 2022-23, decreasing to $48.30 billion in 2023-24, before rebounding to $51.87 billion in 2024-25. In contrast, the trend in imports tells a different story. They experienced a slight decline from $33.79 billion to $31.97 billion in 2023-24, followed by a significant increase to $36.96 billion in 2024-25.

Consequently, the agricultural net surplus has contracted from about $18.88 billion in 2022-23 to $16.33 billion in 2023-24, and further to $14.91 billion in 2024-25. In short, although exports showed recovery in the last year, the more rapid and consistent rise in imports has progressively diminished the surplus. What matters is the direction of the trend: imports are increasing at a more rapid pace than exports, even in sectors where India has traditionally enjoyed a natural competitive strength.

Subsidy hunting and the cropping trap

To understand the rationale behind why India imports what it is capable of producing domestically, it is essential to examine policy design rather than merely agricultural practices. For several decades, agricultural policy has prioritised price stabilisation and the protection of political constituencies over fostering long-term competitiveness. This has resulted in a system that incentivises the pursuit of subsidies rather than productivity enhancement. This has resulted in a system that is highly effective in ensuring the availability of staple goods, yet it is less responsive to the rapidly expanding sectors that currently influence both domestic consumption patterns and trade balances.

Minimum Support Prices (MSPs) power subsidies and low-cost fertilisers provide farmers with incentives to focus on a limited range of crops that the state promises to procure. While this clustering is a rational choice for farmers, it incurs a national cost: the underdevelopment of sectors where demand has outpaced supply. Although urban consumption patterns have diversified, cropping patterns have not followed suit. When processors and retailers cannot rely on consistent domestic quality or timely availability, they turn to imports. The import data from the Directorate General of Commercial Intelligence and Statistics (DGCI&S) vividly illustrate this trend, with rising import values for edible vegetables, fruits and nuts, cocoa preparations, milling products and processed foods.

This phenomenon does not stem from an inability of Indian farmers to produce these goods. Rather, the economic incentives associated with subsidy-backed crops are significantly stronger than those offered by the free-market economics of diversification. The political certainty of MSP procurement outweighs the uncertain profits associated with competing in high-value horticulture or food-processing supply chains.

Furthermore, this policy framework is intricately linked with state-level electoral cycles, resulting in slow change. Governments prioritise price stability to mitigate the political risk of food inflation, perpetuating the existing cycle.

Also read: India’s fiscal future depends on credibility, not just growth rate

Imports as a policy safety valve

In response to sharp price increases, governments frequently mitigate import restrictions or reduce tariffs in order to expedite the entry of essential goods into the market. These interventions offer short-term consumer stability and help smooth volatility. However, they come with a trade-off. When imports readily address domestic gaps, there is a diminished incentive for firms and supply chains to invest in enhancing local production, improving storage facilities, or upgrading quality standards. The ease of importing may inadvertently decelerate domestic capacity building.

Over time, this leads to a pattern where imports become the default response to supply constraints. Farmers, prioritising reliability, may find diversification into new crops less appealing, favouring markets with predictable returns. Consequently, India’s import expenditure increases even in sectors where natural conditions and farmer capabilities suggest strong domestic potential. This does not imply that India is incapable of manufacturing these items; it indicates that the existing framework makes it easier to import them than to establish robust domestic supply chains.

This pattern is evident in the data. Edible oil imports remain structurally high despite India’s suitability for oilseed cultivation. Imports of cocoa preparations have increased as demand surpasses domestic capacity. Dairy imports tend to rise in years when domestic production tightens. India’s reliance on fertiliser imports exemplifies a broader trend. According to the Department of Fertilisers, approximately one-third of India’s urea requirements and a significant portion of phosphatic and potassic fertilisers are imported, despite the existence of domestic production capacity in several sectors.

This dependency increases when global prices decrease or when domestic gas supplies become constrained. The convenience of importing, coupled with heavily subsidised retail prices, often results in long-term investment in domestic production and nutrient balance being deprioritised. As the demand for crop diversification grows, ensuring more resilient fertiliser supply chains will be crucial for strengthening India’s overall agricultural competitiveness. These are not isolated occurrences but reflect a broader structural challenge: the system is designed to maintain stability rather than enhance competitiveness.

A forward-looking strategy would aim to retain the stabilising benefits of trade while also bolstering incentives for domestic investment, diversification and value addition. The objective is not to restrict imports but to ensure that India’s inherent agricultural strengths translate into a broader, more resilient export surplus.

Also read: The math is clear — buying Russian oil is now a losing deal for India

The cost of an underperforming trade surplus

The diminishing agricultural trade surplus is a tangible concern, impacting the resilience of India’s balance of payments. Historically, agriculture has served as a reliable buffer against fluctuation in services or manufactured exports. As services exports increase and manufactured exports fluctuate, agriculture was expected to provide stability. However, it is currently losing its footing.

Countries that dominate global food markets, such as Brazil, Argentina and Thailand, utilise their agricultural surpluses as macroeconomic stabilisers. Despite its natural resources, India is relinquishing this advantage. The rising imports of products that India has the potential to produce domestically result in higher foreign exchange outflows and increased vulnerability to global commodity price fluctuations. The opportunity cost is immense. If India had aligned its production potential with competitive supply chains, its agricultural trade surplus could have been two or three times its current level. Such a surplus could have offset energy import expenses or alleviated currency pressures. Instead, India is increasingly importing goods that its farmers could profitably cultivate. The issue stems from a policy design problem rather than productivity.

Fortunately, the path forward is clear. Addressing subsidy distortions, enhancing quality infrastructure, promoting storage and cold-chain investment, establishing predictable tariff regimes, and shifting procurement incentives towards diversification can restore balance to the system. The budgetary emphasis on oilseeds mission programs, and horticulture clusters is a step in the right direction, but sustained commitment is essential. India’s farmers require enhanced competitiveness rather than increased protection. As illustrated in the chart, the country stands at a critical juncture. Agricultural imports are rising, exports have stagnated, and the surplus is diminishing. However, this trend is not destiny; it is a consequence of past decisions and can be reversed by the choices made now.

Bidisha Bhattacharya is an Associate Fellow, Chintan Research Foundation. She tweets @Bidishabh. Views are personal.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)