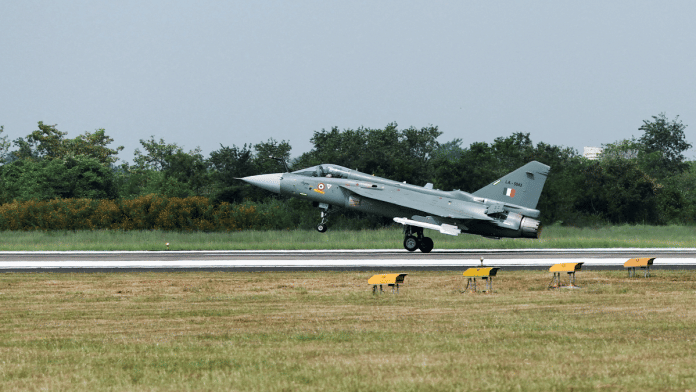

India’s aerospace sector confronts a grim reality, with scant light on the horizon. Two flagship projects designed and substantially ‘made in India’—the Tejas fighter and the Dhruv helicopter—are both under a cloud following fatal accidents that are under investigation.

Tejas deliveries to the Indian Air Force (IAF) lag severely, hampered by delays in the US–sourced F-404/414 engines. Meanwhile, the maritime version of Dhruv has been grounded for 11 months amid probes into a potential design flaw.

The industry has ambitious plans for two fifth-generation successors to the Tejas: the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft and the Twin-Engine Deck-Based Fighter. Yet, both projects remain at the blueprint stage with no prototypes built, possibly stalled by indecision over imported engines. Compounding these delays is the stalled indigenous GTX-35VS/Kaveri engine, under development by the DRDO’s Gas Turbine Research Establishment (GTRE) since 1986. First tested in 1996, this project has made erratic progress over 39 years, plagued as much by design and performance shortfalls as by a lack of vision and resolve on the part of the DRDO.

Historically, every major aerospace power has mastered airframe as well as aero-engine design, enabling sovereign control over aircraft projects. India must aspire for the same.

Institutional inertia

It is ironic that India, the world’s second-largest arms importer, also happens to possess one of the world’s largest defence technology and industrial bases (DTIB). This comprises the DRDO—with its large cadre of talented scientists and a network of 50 laboratories—backed by the production facilities of 16 defence public sector undertakings and ordnance factories. For seven decades, this ecosystem has churned out “indigenous” hardware, fostering a national illusion of self-sufficiency. In truth, much of it involves merely assembling imported kits or licensed production with royalty payments, masking a deep import dependence.

Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL), India’s aerospace giant, exemplifies this. Since the 1950s, HAL has delivered approximately 3,000 aircraft and 5,000 aero-engines of British, French, and Russian lineage. Despite decades of licensed manufacturing and overhauls, HAL’s engine divisions failed to grasp the essentials of metallurgy, precision engineering, tooling, or machining. This reflects institutional inertia and a myopic vision that lacks the drive for technological independence.

India’s political establishment must also carry a share of the blame. Since the 1960s, the country has poured billions of dollars into Soviet/Russian, American, French, and Israeli coffers for weapon purchases; in some instances, saving their companies from plunging into bankruptcy. Other sectors, such as civil aviation, energy, and heavy industry, too, are big spenders abroad. But no government has tried to leverage these huge transactions to compel foreign vendors to part with advanced technology for India’s laggard DTIB.

Contrast this with China. From a 1950s baseline, akin to India’s, China revolutionised its military-industrial complex through ingenuity and resolve. Upon its founding, the People’s Republic of China received massive infusions of arms from a fraternal USSR. But as ideological rifts emerged, Moscow curtailed aid. Foreseeing the split, Chinese leaders retained Soviet hardware and blueprints. Post-rupture, Mao Zedong decreed a national campaign of “guochanhua”, which was a reverse-engineering blitz. In two decades, China indigenised Soviet hardware, from rifles to jet fighters, tanks, warships, submarines, and missiles. Sans licenses, these efforts often yielded flawed designs and resulted in accidents, but the Chinese were not risk-averse and persevered.

Recognising the pivotal role of aero-engines in military aviation, Deng Xiaoping initiated a jet-engine project as far back as 1986. After spending billions and encountering many failures, China succeeded in producing the WS-10 aero-engine, based on the French-American CFM56, under licensed production. Improved versions of the WS-10 now power the bulk of the burgeoning People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) fighter fleet. It is also speculated that these engines power the prototypes of the recently unveiled sixth-generation J-36 and J-50 fighters.

Against this backdrop, the IAF faces formidable operational challenges in a potential two-front war scenario against the PLAAF and Pakistan Air Force. Currently fielding 29 squadrons—far below its sanctioned strength of 42 squadrons—the service will have its hands full, countering the threats from diverse azimuths and geographies. While deliveries of Tejas Mks 1 and 1A are delayed due to production lag, foreign acquisitions remain stalled amid bureaucratic processes.

Also read: How China reads US National Security Strategy—a return of America First in new language

Closing tech gap with China

Achieving “atmanirbharta” or self-reliance remains a profoundly worthy aspiration, but without a visionary roadmap—milestones, timelines, and strict oversight—it remains but a slogan. To unlock the promise of its aeronautics industry, India must unshackle it from the apathetic Department of Defence Production and permit the involvement of private-sector dynamism, innovation, and efficiency. Foreign procurements—Rafales or Sukhoi Su-57s—are mere palliatives and cannot help us close decades-old technology gaps. New Delhi must aggressively harvest global expertise from wherever it can.

Apart from industrial espionage in the West and disregarding intellectual property rights, China has instituted a “Thousand Talents Plan”, using financial incentives to poach minds from abroad to boost its research and development (R&D) efforts. In a rare flash of inspiration, India had also acquired the services of German designer Kurt Tank in 1956, who helped HAL design its first successful jet fighter, the HF-24 Marut.

The recently concluded Labour Mobility Agreement between India and Russia offers New Delhi a strategic window of opportunity. As India helps mitigate Russia’s dire demographic void by exporting skilled labour, it must seek something in return. As a quid pro quo, India should demand the services of top Russian experts on long-term contracts in fields where it faces technological challenges. Such an arrangement could help New Delhi leapfrog its R&D hurdles and make up for lost time in the global technological race.

Arun Prakash, a naval aviator, is a former Chief of Naval Staff and Chairman, Chiefs of Staff Committee. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)

Incisive and apt

Adm Prakash has rightly pointed out the lacunae in our defence preparedness. We are reasonably up to date in air defence and guided missile systems. But we are way behind in advanced fighter aircraft systems. Even after our AMCA becomes operational by 2035 , we will still be 10 to 15 years behind others like China who are already testing 6th gen fighters.

Catching up will need an extreme Innovation group who will convert the existing AMCA and tejas platforms into 6th gen ones and start trials in the next 2 to 3 years.