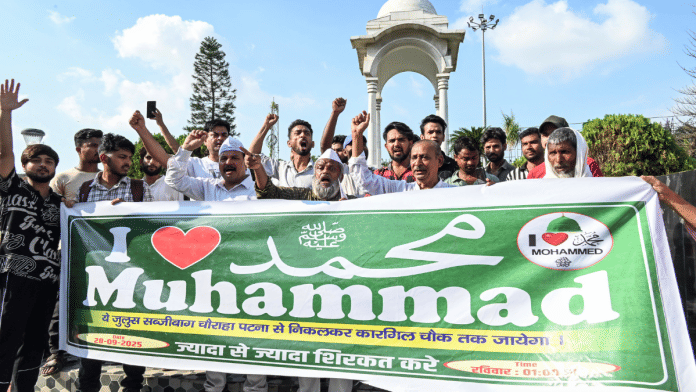

I Love Muhammad”. Is it the Muslim response to “Jai Shri Ram”? If so, how lame! Couldn’t they seek conciliation instead of confrontation? They would find greater resonance if they said, “I Love Ram”. But could they? Would their theology, ideology, religious discourse, political narrative, and societal restrictions let them wear Ram’s love on the sleeve?

The Hindus, on the other hand, as is their sanskar, respect Prophet Muhammad and all other religious figures as much as they respect their own. They never mention the Prophet’s name without a mandatory honorific such as the prefix ‘Hazrat’ and the suffix ‘Saheb’.

There is a long list of Hindu poets who have left a large corpus of Naat, the genre of Urdu poetry that venerates Prophet Muhammad. A couplet by Chandra Prakash Jauhar Bijnori should suffice to illustrate this point:

Main Hindu hoon magar iman rakhta hoon Muhammad par;

Koi andaz to dekhe meri kafir adaai ka.

(I am Hindu, but I believe in Muhammad;

Let them behold the grace of my infidel airs.)

Another poet, Chaudhary Dillu Ram Kausari, published an anthology titled Hindu ki Naat aur Manqabat in 1924. Kunwar Mahender Singh Bedi Sehar, a Sikh, cherished the Prophet in such adorable words:

Ishq ho jaye kisi se koi chaara to nahin;

Sirf Muslim ka Muhammad pe ijara to nahin.

(One may fall in love, they’re helpless against it;

Muhammad is not the monopoly of Muslims alone.)

It’s unimaginable that the Hindu would find anything objectionable in the Muslim’s expression of love for their prophet. And though he is disparaged by Abrahamic religions as polytheistic, the Hindu could be best described as a ‘polymorphic monotheist’. He recognises a single, unitary supreme being manifest in multiple forms, deities, or spiritual realities, rather than a rigid, singular representation. This acceptance of diversity in conceptualising the divine is pithily encapsulated in an aphorism of the Rig Veda, “Ekam sat vipra bahudha vadanti (Truth is one, the wise speak of it in many ways).”

Devotion or war cry?

One of the differences between the Hindu and the Muslim is that the former is not concerned with who believes what and who worships how. The latter, on the other hand, is intrusive about others’ beliefs and worship, and is keen on converting them to his way.

The Hindu recognises every religion to be as true for its followers as his own is for himself. He respects every religious figure and doesn’t denigrate any.

So, who are these ‘I Love Muhammad’ Muslims trying to impress by their public display of affection (PDA) for the Prophet? Is it sincere religiosity or political signalling? If it is political, should it be treated with the same reverence that the Hindus have been culturally accustomed to accord Islamic religiosity? Haven’t they reflexively folded hands and bowed heads when passing by a mosque or dargah, made room for those who wanted to perform namaz on railway platforms or even in the aisle of a train, or been lenient to the employee who has been fasting during Ramzan? Don’t they go into trance listening to qawwalis—most of which are soaked in the veneration of Prophet Muhammad and Islamic spirituality, such as Tajdar-e-Haram, or Bhar Do Jholi Meri Ya Mohammad? Some even have the words of the Quran, depicting the omnipotence of Allah, such as Kun Faya Kun.

And no, this isn’t a tacit admission of the superiority of Islam, as an ordinary Muslim might think. This is the ecumenism of the Indian culture, and the large–heartedness of Hindus.

So, when the name of the Prophet has been so revered by the Hindus as to be above any contention, why this sudden eruption of ‘I Love Muhammad’ processions, demonstrations, banners, stickers, social media posts, and WhatsApp DPs?

One may ask if this purported expression of love is an act of devotion, a profession of faith, or a war cry. Hasn’t “Allahu Akbar”, which simply means “God is great”, been a war cry since the inception of Islam?

Also read: Once you know how UPA handled illegal Bangladeshi immigrants, you see Modi govt’s propaganda

A storm brewing in Muslim hearts

Islam is about Muhammad. There is no Islam besides him. Everyone, every theist, believes in god; but a Muslim is the one who also believes in Muhammad. The book, And Muhammad is His Messenger, by leading scholar of Islam Annemarie Schimmel, has the subtitle, The Veneration of the Prophet in Islamic Piety.

The invocation of the Prophet’s name is a sacred ritual which is performed in solemnity during every namaz. It is recommended that one be in the state of ritual purity, with prescribed ablutions (wazu), when uttering it. Every mention of him is accompanied by Darud and Salam—Adoration and Salutation. His name is not dropped off-handedly, and he isn’t spoken of casually.

So, what does one make of this (sadak chhaap) pedestrian emoji love for him? What is it, if not a cheap politicisation of Muhammad’s name?

Is this #I_Love_Muhammad the proverbial straw in the wind that indicates the storm brewing in the Muslim heart against the government, which they find ideologically impossible to regard as their own, and against which they are ever ready for an insurrection?

Is there another mindless, senseless movement in the making, like the one against the CAA? The Act merely offered expedited citizenship to the people fleeing religious persecution in the neighbouring Muslim countries. It had nothing whatsoever against Indian Muslims.

Is a ground being prepared for the revival of the communal conflict which was endemic to the Secular Raj? After all, it has been a fervent hope of the Hindu Islamists—the Left-liberal reactionaries—to goad Muslims into a major uprising against Modi Sarkar. If a reprisal followed, as it perforce would, the dispensation could be maligned as being majoritarian and fascistic. It could delegitimise the government and pave the path for the restoration of the dynasts of democracy and the royals of the republic.

Desperate for a return to power as they are, the situation seems ripe to them. The toppling of the government in Nepal has given them hope to do the same with an emoji campaign here. They don’t mind if the adventure pits the minority against the majority and leads to civil strife.

A sinister campaign is afoot, sowing the seeds of suspicion about the electoral process with slogans such as ‘Vote Chori’. There is also the tariff warfare against India by the whimsical Donald Trump. Together, they have created an atmosphere in which the anti-Modi forces feel emboldened to go on the offensive, secure as they are in the religious armour.

The Darul Harb mentality

That Muslims harbour a seething resentment against the Modi government is all too visible. But one may want to know if they have any specific grievance that cries for redressal? Is there any systemic discrimination against them, or have they been reduced to lesser citizens? Or is the whole crux of their grievance that this government, elected regardless of their vote bank, doesn’t see the need to be obsequious to them? Earlier, prime ministers and chief ministers paid obeisance to them as kingmakers. If this is their grievance, they should know that the expectation to be appeased is not only undemocratic and unconstitutional, but no longer realistic, either.

Anyone who has studied Indian history would testify that the kind of religious rhetoric that has been building around the ‘I Love Muhammad’ movement was the stock-in-trade of Muslim narrative makers during the pre–2014 Secular Raj. Though Muslim leadership was unctuously feted in the period, their political vocabulary was as steeped in Islamic power theology as it is now—after the overwhelming Islamisation of the consciousness of the Muslim youth.

The drift of their narrative, as much in public articulation as in private conversation, has been anti-state—that is, anti–Indian state. Inevitably so, since in the absence of secularisation of Muslim thought, they can’t help but view the modern through the lens of Fiqh or Islamic jurisprudence. Accordingly, Muslims can’t identify with a state which isn’t under Muslim rule.

It’s a Land of War, Darul Harb, where they remain in a perpetual state of war—psychologically, if not physically. Though this formulation is no longer propounded, its logic runs deep into the Muslim psyche. No surprise, therefore, if the lexicon of their political discourse has remained supremacist, belligerent, and militaristic. Mentally, they are always in war mode against Hinduism and, therefore, against the Hindus and the Indian state. Those who look sympathetically on this condition call it their ‘siege mentality’.

Also read: Israeli society is in collective denial over what is happening in Gaza. Media isn’t helping

Muslim victimhood

The end of the Muslim rule in India, and the eventual establishment of the nation state, has not only made the Muslims dissociate from the sense of belonging to the state, but has also filled them with a profound sense of victimhood. The equality guaranteed by the Constitution is construed as a fall from the pedestal of superiority.

Muslims have internalised a sense of victimhood not because they are actually persecuted, discriminated against, or denied religious freedom, but because India is not a Muslim state. Since Islamic political theory doesn’t accord equality to non–Muslims, its followers are ideologically incapable of appreciating the equality offered by the modern, secular state.

Compelled by circumstances, though, there have been some pragmatic, albeit half–hearted, attempts to dilute the theological antipathy that Muslims hold toward the Indian state. Some jurisprudential improvisations were tried to make the reality somewhat palatable by changing India’s characterisation from Darul Harb to Darul Aman (Land of Peace) or Darul Ahad (Land of Concord). These attempts proved to be incompetent because they lacked conviction and theoretical groundwork. It was a mere window dressing. What was needed was a restructuring of Islamic thought along pluralistic lines, shedding the supremacism of Islam, and recognising the equality of religions. Only then could a reform have some meaning.

A fundamental question presents itself. Why should there be an Islamic gaze on India, and why should the country’s character be judged by the criteria of an exogenous religion? Rather, why couldn’t Islam be seen with an Indian eye and assayed on the touchstone of the Indian notion of dharma? This couldn’t happen because of the centuries of power asymmetry between Islam and India, where Islam had been the ruler and India, the ruled. Islam substantially changed India, but itself remained unchanged. Thus, we have a genre of books such as Tara Chand’s Influence of Islam on Indian Culture (1936), but hardly one with a title such as ‘Influence of India on Islam‘. Interestingly, whatever Indianness did seep into Islam is regarded as bid’at—an innovation which distorts the authentic form of Islam. On the other hand, the supposed influence of Islam on the Indian culture—the concept of egalitarianism being the most advertised one—is celebrated as the redemption of India.

Such asymmetry of power between the entities has continued to this day. The insurrectionary eruptions that we see every now and then are reflex actions to protect the legacy of entitlements—the pension for having once been the rulers. One such entitlement is Islam’s claim on the public space—big mosques by the roadside, namaz on thoroughfares, religious processions winding through the interstices of cities, azan by loudspeakers, scurrilous misrepresentations of Hinduism in Islamic literature, and aggressive rhetoric of identitarian politics.

Don’t weaponise Prophet’s name

The unstated agenda behind the ‘I Love Muhammad’ agitation is about the uncontested claim of Islam on public spaces in India. It’s a legacy of centuries of rule. However, Muslims would do better to think about whether the public performance of religion strengthens or weakens secularism—the idea in which they have the highest stake.

Regardless of what their Left-liberal patrons expect of them, Muslims should introspect on whether it’s a good idea to weaponise the Prophet Muhammad’s name in street politics. If a sanctity is politicised, it will, inexorably, elicit a counter–narrative too, and that will trigger a downward spiral, which will be difficult to control. Even the Islamists, who consider Islam a political religion and regard the Prophet as a political figure, have never been so frivolous as to drag his name into such lowbrow street politics.

For a sincere Muslim, Prophet Muhammad’s name is far too exalted. This is what the Quran (94:4) says about him: “Wa Raf’ana Laka Zikrak (And we raised high your name).” So, dear Muslims, don’t pull it down.

Ibn Khaldun Bharati is a student of Islam, and looks at Islamic history from an Indian perspective. He tweets @IbnKhaldunIndic. Views are personal.

Editor’s note: We know the writer well and only allow pseudonyms when we do so.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)

Mr. Bharati does not hedge. His essays command the reader’s attention from the get-go… The way he gets to the heart of any question that stirs his consciousness is staggering. This article of his, too, like many earlier ones, bears testimony to what a fine mind he is. Armed with a deep knowledge of Islam, its history and of the psyche of the faithful, he presents his arguments so logically and with such authenticity that only those not enough knowledgeable or out-and-out intransigent would have the courage to be on at him.

Mr. Bharati does not hedge. His essays command the reader’s attention from the get-go… The way he gets to the heart of any question that stirs his consciousness is staggering. This article of his, too, like many earlier ones, bears testimony to a fine mind that he is. Armed with a deep knowledge of Islam, its history and of the psyche of the faithful, he presents his arguments so logically and with such authenticity that only those not enough knowledgeable or out-and-out intransigent would have the courage to be on at him.

The central question of the article is trite (“Would their theology, ideology, religious discourse, political narrative, and societal restrictions let them wear Ram’s love on the sleeve?”)

The entire faith begins with a repudiation of everything it defines as outside its axioms as low and unworthy (“There is no god but God”, or by implication, “No deity is worthy of worship but God”). It should hardly come as a surprise, then, that anyone who “testifies” to this “truth” must necessarily, as a corollary, not just opt out of, but actively oppose any “respect,” symbolic or otherwise, for any “other.”