On a bright sunny morning, Lakpa, the forest guard, had come running to see us. Such was his excitement that he did not even care to park his scooter, which he left lying in the middle of the road. “There is a red panda on the tree,” Lakpa shouted repeatedly while rushing to get within earshot. This was in 2009, and we were at the gate of the Barsey Rhododendron Sanctuary in West Sikkim, preparing to leave for our day’s field work. Excitedly, we dashed into the car and drove to the spot where the red panda had been sighted no more than five minutes ago. Lakpa quickly got off the vehicle and scanned the treetops and the ground below. As a local resident, Lakpa knew these forests like his backyard. However, this familiarity with the natural surroundings had not diminished his interest in wildlife even a tad bit.

There was no sign of the panda. It was gone, and with it, my first chance of catching a glimpse of this hard-to-sight creature in the wild. Lakpa was more disappointed than all of us put together. He had made it his mission to show us the red pandas that he had grown up seeing. He understood what the sighting would mean for us in our quest to understand the animal better. He knew the significance of the red panda as an indicator species and that the sighting of one was a sign that all was well. Besides, there is no greater joy for a forest guide than the one derived from the experience of a shared sighting. Little did we know then that it would be our last forest trip together, and Lakpa’s dream of gifting us a red panda sighting would remain unfulfilled, for our young forest guide passed away a year later.

Working for conservation is as much about the animals and forests as it is about the people who live around them and those who work to protect them.

Also read: India’s green energy goals have a serious problem – the Great Indian Bustard

Beyond chasing numbers

The red pandas live in the high altitudes of the Himalayan range and are listed as ‘endangered’ in the IUCN Red List.

So, how many red pandas are there in Sikkim? The question is simple, the answer not so much. It is difficult to tell one red panda from another; therefore, a visual count is out of the question. Add to this, their extremely shy nature, and the task of coming up with exact figures becomes next to impossible. Genetic methods can identify individual red pandas from the DNA extracted from their scats and are slowly being deployed to estimate the species’ population. But even with these at hand, adequately sampling red panda habitats remains a challenge due to the rugged mountainous terrain. In India, red pandas are found in the three Himalayan states of Sikkim, West Bengal (Darjeeling and Kalimpong districts) and Arunachal Pradesh. But beyond chasing exact population figures, there are other elements for conservation planning that merit greater attention.

WWF-India has been working in the Sikkim landscape on red pandas for the last 10 years. The work has mainly focused on understanding the extent of the animal’s habitat within the state and digging deeper into the animal’s ecology. These critical pieces of information help develop future interventions that would enable forest managers and communities to ensure the long-term conservation of the species and its habitat.

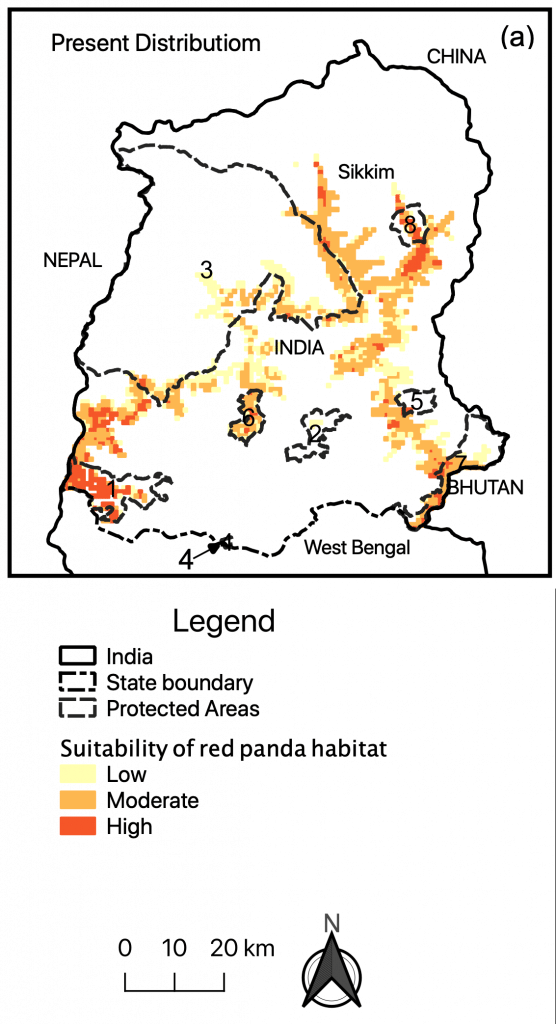

Field research teams spend countless days and nights in forests scouring for red pandas or their evidence in the form of droppings or pugmarks. The presence and absence of the red panda signs coupled with information on dominant tree species, shrubs and herbs, availability of water and topography help develop a bigger picture. This helps us understand the habitat use and preferences of the red panda, their distribution and factors that explain their presence or absence in different areas. Modern analytical tools allow a fairly accurate mapping and prediction of the species’ potential habitat for Sikkim based on the information collected by the field teams.

Also read: Red pandas in India are being trafficked into extinction. And laws stand in the way

Beyond protected areas

Protected areas are demarcated with the hope that some measure of conservation is achieved in these patches. But animals know no boundaries and occupy spaces that can go far beyond protected areas. Sikkim has eight protected areas (PA) that spread across its four districts. Except for the Kitam Bird Sanctuary, all of these PAs are located at elevations that are suitable for red pandas. While most of these protected areas in Sikkim harbour red pandas, our research findings show that as much as 66 per cent of their habitat extends to contiguous forests that are beyond the PAs. This has been arrived at by combining data from extensive fieldwork gathered by the teams with modelling exercises.

But on the ground, how good are these potential habitats that have been identified through modelling approaches? The field teams get into action again. Locations on the map showing potential red panda habitats are identified. They walk the forests looking for red pandas or their signs to validate what the map indicates. Encountering red panda signs or, in rare cases, the red panda itself proves that the potential habitats hold populations.

Field studies in the forest ranges outside of the PA network in the North District have yielded valuable evidence of red panda presence. Camera trapping exercises have captured photographs of red pandas around the Naga-Singhik range suggesting extensive use of these habitats by the species in the winter months. Red panda evidence was collected from areas contiguous to Shingba Rhododendron Sanctuary, indicating their presence in these forests.

But it is from the field sites of East Sikkim that the team guided by locals from the village of Yali had the most rewarding experience. Much to the surprise of the community members, who were of the firm belief that the forests below Kyongnosla held no red pandas, the team encountered one at very close quarters on a cold November afternoon. Red pandas had not been sighted in these forests for so many years that the animal had achieved a somewhat mythical status, a creature that lived only in the memories of the older folks. Therefore, the sighting was received with much joy and great hope by the community.

Also read: Rhino, snow leopard, red panda — the endangered species Modi govt wants to protect

Shrinking spaces

Crowning the top of the hill on the opposite side of Gangtok town is the Fambonglho Wildlife Sanctuary. Surrounded by settlements that are ever-expanding, the sanctuary is rapidly losing its connectivity to other contiguous forest patches. Once housing a thriving population of red pandas, recent studies have yielded very little to no evidence of the animal’s presence.

These shrinking and fragmented spaces define the state of forests everywhere. With developmental priorities taking centre stage more than ever before, there is an urgent need to identify areas that should remain inviolate.

After my missed opportunity in 2009 in Barsey, I got a chance to sight the red panda in 2012 right from my car window. One dusky evening in August, as we approached the village of Lachen in North Sikkim, a pair of unmistakable white-tipped ears stood out from behind a small rock just by the roadside. Could this be our moment? A flash of red, a striped tail, and all our doubts was laid to rest. We immediately stopped the car and jumped out to see the back of the animal vanishing into the bamboo thicket below the road. Much to our dismay, the joy of the sighting was short-lived, as the area was littered with plastic waste, and the animal, in all probability, was feeding on some leftovers.

Priority spaces that lie outside the protected area network critical for the future of red pandas need to be safeguarded from all kinds of disturbances. While interventions through community-led initiatives to reduce habitat degradation will give long-term results, the larger developmental projects also need to be looked at critically. This has become more pertinent in the wake of recurring disasters that serve as grim reminders of the fragility of our mountains.

Safeguarding these priority spaces for the future by ensuring a high level of protection is the only way forward. For when we safeguard the red panda’s habitat, we protect the forests, we protect our water sources, we prevent avoidable disasters, we protect our future. The precious gift of a red panda sighting is one that we must pass on to our children.

Priyadarshinee Shrestha is Team Leader, WWF India, Khangchendzonga Landscape. Priyadarshinee has been working with WWF India for the last 14 years, managing the programme for Sikkim and Darjeeling Hills. Views are personal.

(Edited by Neera Majumdar)