When a former chief economic advisor persists with a question, it is typically because the answer still matters. With the publication of his new book and a fresh round of interviews, Arvind Subramanian has revisited an argument he initially presented in 2019: that India’s reported GDP growth in the years following the 2011 methodological revision may have been overstated by as much as 2.5 percentage points a year.

The claim is not new; however, the context in which it is resurfacing is. Nearly six years after the original paper incited official rebuttals and academic discourse, the fundamental question remains unresolved: Does India possess a reliable mechanism to validate its growth figures in an economy undergoing rapid transformation?

What Arvind Subramanian actually argued

Subramanian’s original argument was often oversimplified as a mere discrepancy between GDP and a few traditional indicators. In reality, it was based on a more structured empirical approach. In his 2019 paper, Subramanian asked whether India’s GDP began exhibiting different behaviour following a specific breakpoint—the 2011-2012 rebasing and methodological overhaul—compared to its historical performance and that of other countries. To address this, he employed what economists refer to as a difference-in-differences style approach.

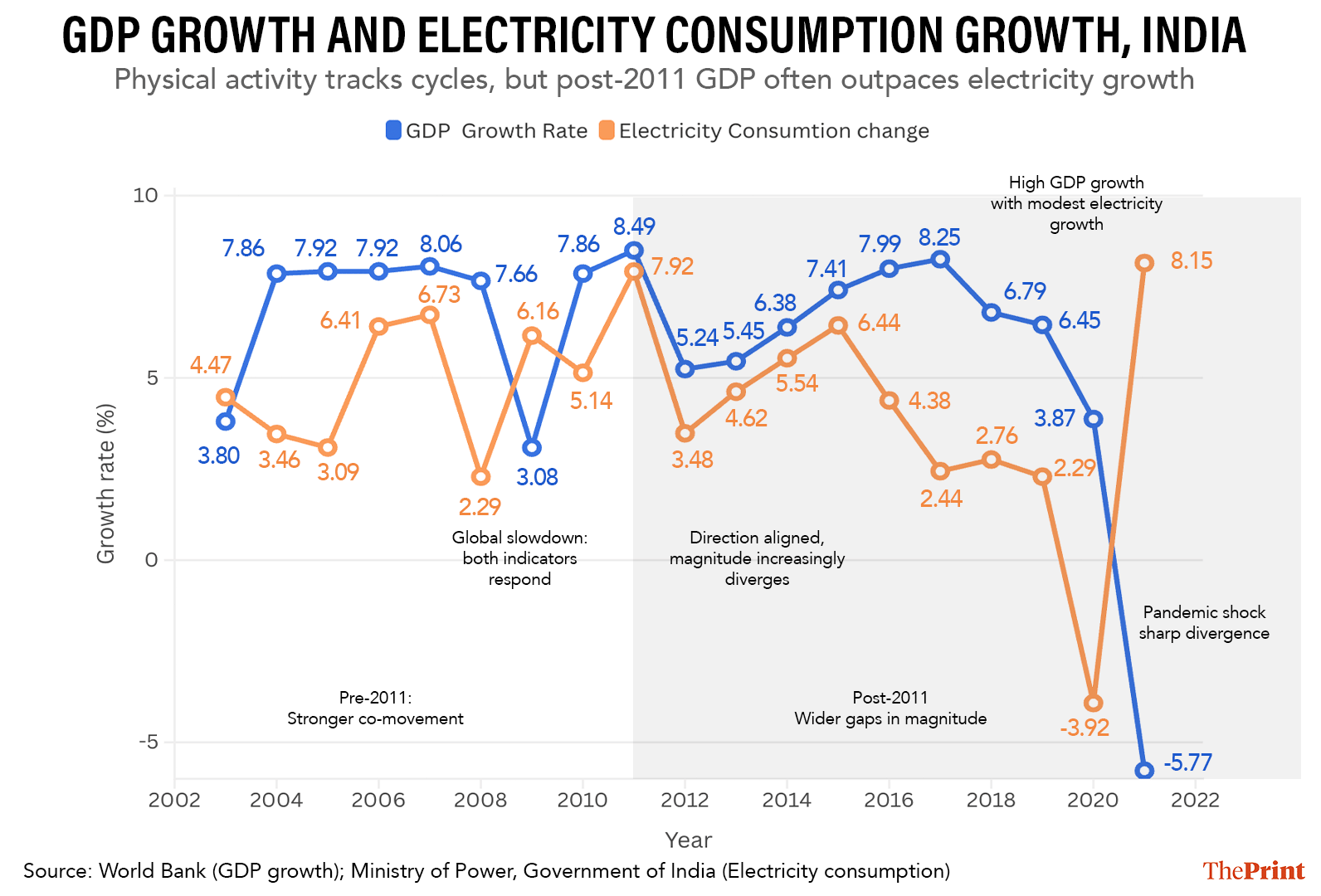

When stripped of jargon, the logic is straightforward. Initially, it is observed that before 2011, India’s GDP growth generally aligned with indicators such as electricity consumption, trade flows, credit growth, railway freight and petroleum use. Subsequently, it is noted that post-2011, GDP growth remained robust despite a weakening in many of these indicators. Finally, this change is compared not in isolation but against the experiences of other economies during the same period.

If global forces, such as slower trade or energy efficiency gains, were responsible, similar divergences should be evident elsewhere. Subramanian identified that India’s divergence was unusually pronounced. That “extra” divergence formed the basis of his estimation that growth may have been overstated.

The non-stationarity defence

This was not presented as a definitive conclusion but as an anomaly—something statistically unusual that deserved explanation. Nevertheless, the response was swift and sceptical. Government economists and several academics contended that the method relied on a fragile assumption: that the relationship between GDP and these indicators should remain stable over time.

This brought a technical concept into focus: the non-stationarity of correlations. In simpler terms, it implies that the relationship between economic variables does not remain constant as an economy evolves. Indicators that were effective in a manufacturing-heavy economy may lose relevance as services, digital activity, and intangible output expand. Critics argued that electricity use, freight movement, and fuel consumption are goods-biased measures. If growth increasingly stems from software, finance, healthcare, logistics platforms, or digital services, it may leave a weaker physical footprint. A breakdown in correlation, therefore, does not automatically imply mismeasurement; it may reflect genuine structural change.

Although physical activity continues to be influenced by economic cycles, the period following 2011 indicates that GDP growth has increasingly surpassed electricity consumption. This trend suggests that traditional proxies alone are no longer sufficient to validate economic growth.

This is a serious and valid critique. Economies do not merely grow; they transform. Treating historical correlations as permanent benchmarks would be erroneous. In this sense, the non-stationarity defence is not an evasion; it is an important reminder of the significance of economic structure.

However, this response remains incomplete, as well.

Structural change may weaken relationships, yet they seldom eliminate them entirely and simultaneously. The divergence observed post-2011 manifested across various unrelated indicators, such as energy, trade, transport and credit, simultaneously. While growth driven by the services sector may be less energy-intensive, it still leaves traces. Offices consume electricity, firms engage in borrowing, workers commute, and consumers spend. A sustained acceleration in growth should be evident beyond the confines of national accounts.

Also read: Why India needs more mining to power its manufacturing future

The missing piece: alternative validation tools

More critically, the argument of non-stationarity elucidates why traditional indicators may be inadequate, yet it fails to propose suitable alternatives. And this is exactly where the discourse has stagnated. Rather than advancing toward improved validation tools, India remains stuck in a binary debate: either fully trust the GDP or entirely distrust it.

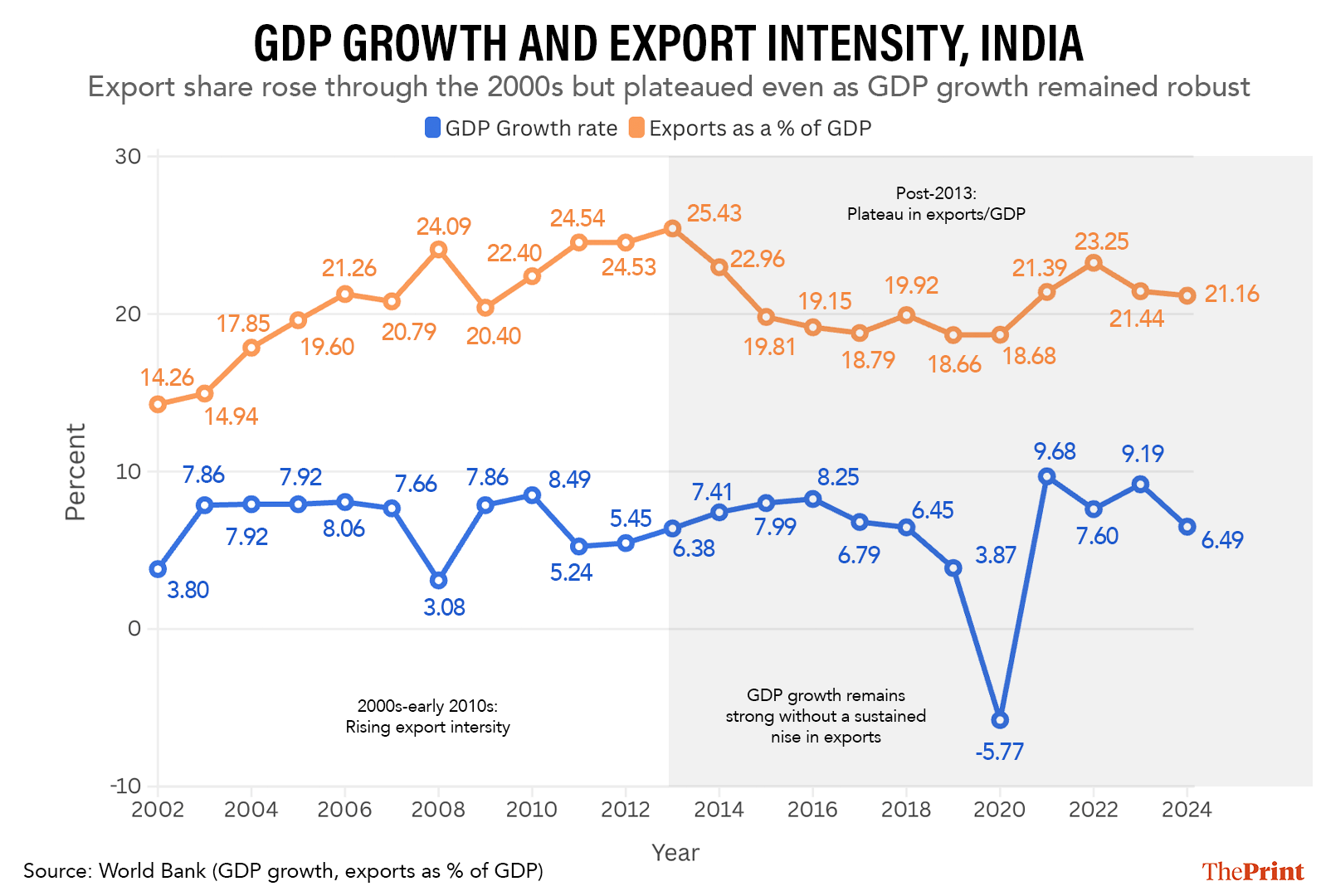

During the 2000s and early 2010s, India’s export share of GDP experienced a steady increase; however, it subsequently plateaued and declined post 2013, despite the fact that GDP often remained robust. This indicates that recent economic expansion has not been strongly reflected in the intensity of the tradeable sector.

This is an erroneous framework. If India’s economy has indeed evolved beyond reliance on freight wagons and electricity meters, then growth should be observable in indicators that reflect a modern economy. If growth is neither entirely manifested in physical activity nor tradable goods, where and how it should be substantiated. The solution is not to discard traditional measures but to augment them with a more comprehensive and representative set of indicators.

First, indicators of the services-sector must take centre stage. The services sector now constitutes a substantial portion of GDP, yet it remains inadequately represented by physical proxies. Metrics such as the services Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), telecommunications data usage, airline passenger traffic, hotel occupancy rates, and financial-services volumes offer a more accurate depiction of the momentum within the sectors driving economic growth.

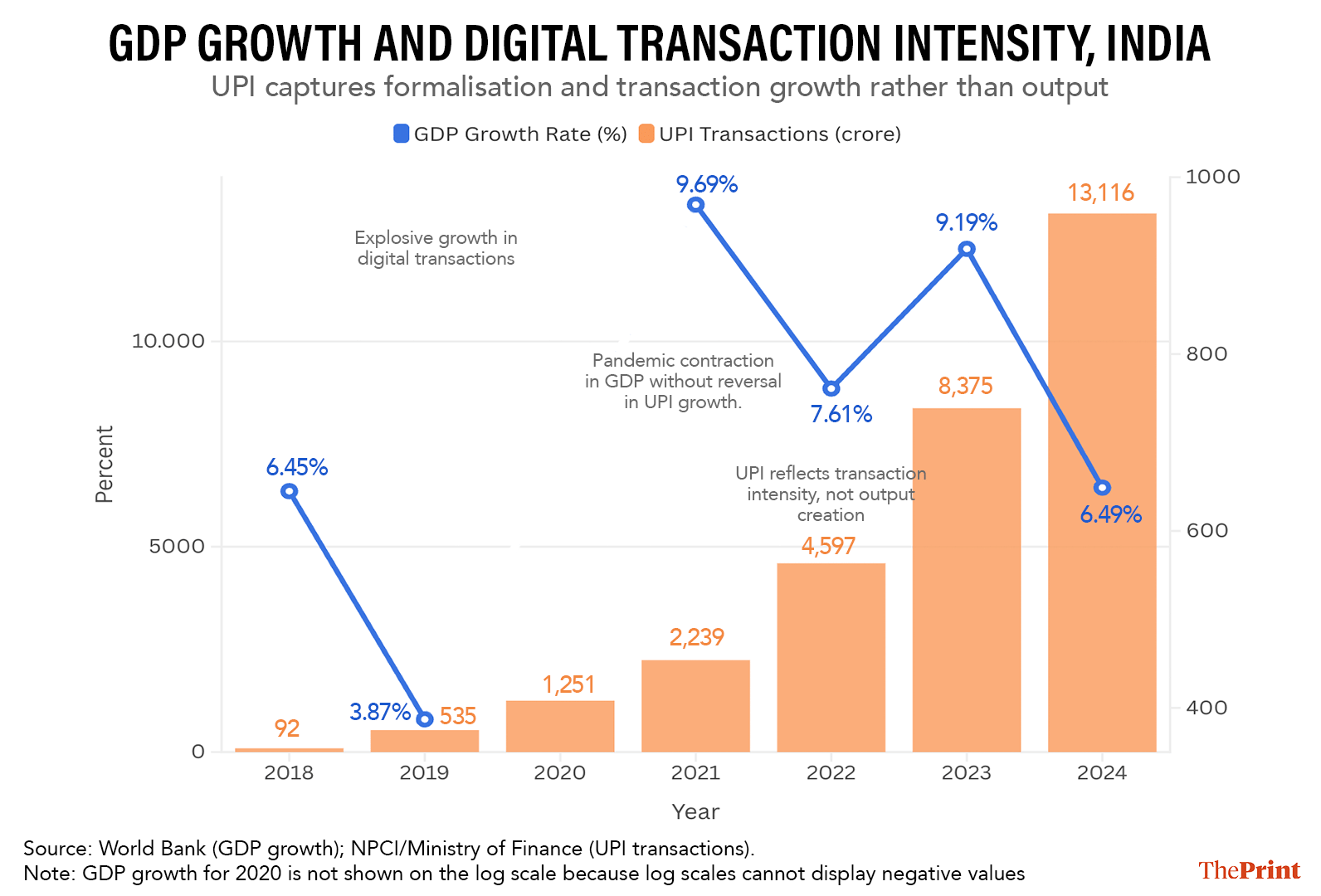

Second, signals from the digital economy should no longer be regarded as merely anecdotal. The expansion of digital payments, e-commerce, logistics platforms and online services has fundamentally altered the mechanisms of value creation and exchange. Indicators such as Unified Payments Interface (UPI) transaction values, Goods and Services Tax (GST) e-way bills, and platform-based activities—meticulously adjusted to prevent double-counting—provide insights into economic intensity that traditional data sources may overlook.

Since 2018, UPI transactions have experienced exponential growth, even as GDP growth has remained within a relatively narrow range and briefly contracted during the pandemic. This divergence neither validates nor invalidates GDP growth; rather, it underscores how an increasing portion of economic activity now manifests in forms—formalised, digital, and services-led—that do not leave strong physical nor tradeable footprints, highlighting the necessity for a broader validation framework.

Third, if growth is increasingly formalised, it should be reflected in firm-level and tax data. Trends in GST filings, corporate tax collections, payroll registrations and company profitability can serve to validate whether output growth is accompanied by formal economic activity.

Fourth, labour-market indicators deserve greater consideration. Sustained high growth should manifest in employment, real wages or hours worked, particularly within the services sector. Growth that consistently fails to translate into job creation or income generation raises legitimate concerns, even if it is statistically recorded.

Finally, independent sources such as satellite-based night-time lights and urban expansion patterns can function as impartial cross-verification tools. While these indicators are imperfect and somewhat rudimentary, their value lies in their independence from the official statistical system, thereby enhancing the credibility of any validation exercise.

No single indicator can conclusively resolve the debate. However, collectively, such a dashboard would achieve what the current system does not: assess whether headline GDP growth aligns with the tangible economic reality. Viewed in this context, Subramanian’s renewed intervention is less an attack on institutions and more a reminder of unfinished business. The credibility of growth statistics is not solely dependent on methodological sophistication but also on transparency, replicability, and corroboration. If growth is genuine, it should be observable across multiple dimensions. If it is not, early acknowledgment allows for policy adjustments.

The objective, therefore, is not to defend or contest previous estimates, but to modernise the methodology for validating growth in a rapidly evolving economy. India’s statistical system has consistently adapted to structural changes; extending this adaptability to the validation of growth would enhance, rather than diminish, confidence in the data. A government that leads this initiative would transform a longstanding doubt into a sustainable institutional asset.

Bidisha Bhattacharya is an Associate Fellow, Chintan Research Foundation. She tweets @Bidishabh. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)