Two kinds of ideas creep up in India’s political and social discourse. One, the regular denunciation of Macaulay, colonialism, etc. The other claims that India was Vishwaguru, that the Vedas contain modern science, and so on. Both have one common element: Looking backward.

Both criticism and praise are rooted in the past. This means that the present scenario, current challenges in the world or debasements within the country are largely ignored.

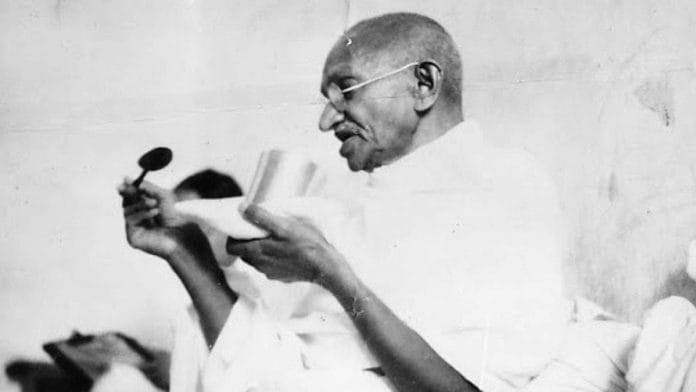

Hindu leaders in general have been backward-looking. MK Gandhi took the lead in displaying this trait, rather proudly, unwittingly strengthening it. His book Hind Swaraj (1909) is full of claims that glorify the Indian past vis-à-vis modern European thought. He even belittled the British Parliament.

The trait is defeatist and fatalist, but poses as being brave and superior. Such has been the main crop of nationalist leaders ever since.

They mostly live in the past. Speak in irrelevant and exaggerated terms. Indulge in habitual bragging, criticising or belittling someone or other. They reveal neither a vision for the future nor for the present. Their preachiness and volubility disguise it, at least to the domestic audience.

For most Hindu leaders, comfort and office have been ends in themselves. Despite numerous failures and blunders, they refuse to step aside and allow others a chance. Thus, institutionalising incompetence, unaccountability, and gerontocracy.

Even in abusing and condemning, they overlook present enemies who can inflict retaliation. They choose safe targets: Thomas Macaulay or Jawaharlal Nehru. Even in the Parliament, they hardly ever discuss a current problem or threat in a genuine manner.

They condemn ‘colonialism’ but do not pay attention to the fact that every year, thousands of young professionals settle abroad. The leaders do not care about retaining and encouraging talented people in the country. On the contrary, they take pride in ‘persons of Indian origin’ who run American companies. They forget that this ‘achievement’ is the result of Macaulay’s vision.

Also read: RSS centenary isn’t a cause for celebration. It’s veered away from Hedgewar’s objectives

Intellectual decline

In view of this attitude, the British Raj in India was definitely better. If foreign rule is acceptable—provided the path to personal security and advancement is open—then that was provided by the British Raj so handsomely. In fact, many great Indians testified that after centuries of atrocities and chaos, British rule provided peace, security, and progress to Indians. Hindus also received, in addition, socio-political equality denied to them under the Muslim rulers.

But to think through everything together in a discerning manner seems beyond the ken of Hindu leaders. They stick to fixed ideas, do routine work, and remain silent on difficult issues. Most leaders of all parties are like this: Weak in thought and hungry for office. Even the so-called ‘party’ work is seen as a ladder for government offices. Which is seen as lucrative, not a place of serious duty. It has been fundamentally different from the ‘colonial’ rulers. That made all the difference.

Check the parliamentary records or media headlines for years together. It would be extremely difficult to find a bipartisan discussion that tackles, in earnest, a social problem or national issue. Everything taken up is mostly an excuse to serve a party interest or blame others.

As collateral damage, all-around intellectual decline is evident. For two decades after 1947, the situation was little different. Leaders and scholars then devoted time to thinking about policies and issues. The reason was also the education and tradition of British rule, which was sincere, largely free from undeclared vested interests. It was under the influence of that tradition that Indian leaders started to make an Indian rule.

Therefore, whatever quality and seriousness existed in parliamentary or literary debate up to the late 1960s may be credited to British educational exposure. Liberalism, constitutionalism, local self-administration, values of equality, voting, democracy, socialism, the entire public education system from school to university, and newspapers, magazines—all were learnt from the British. None of it existed here in pre-British regimes.

Hence, the decline in leaders’ thinking and general intellectual discourse from the 1970s onward is an indigenous Hindu phenomenon. There is hardly any document proclaiming a national vision. Instead, there have been only changing slogans. ‘Socialism’, ‘Sarvodaya’, or ‘Hindu Rashtra’. ‘Anti-Congressism’, ‘Total Revolution’, etc, were merely names to grab government offices. None had any coherent vision.

Now the leaders are not even capable of giving slogans. They manage with inane catchphrases and road shows. All this indicates intellectual emptiness. Now, few leaders seem to possess ideals to which they are loyal.

For the past sixty years, we’ve only seen Hindu leaders having petty squabbles over chairs. Even on foreign tours, they run down their domestic rivals. There is mutual animosity. Provoking and inciting people and thinking of schemes for votes appear to be their main concern.

After the 1970s, when ‘socialism’ and ‘non-alignment’ became obsolete, no thinking emerged in the Indian mind about the country. Everything became centred on harvesting votes through appeasement and casteism. Those who introduced the slogan of ‘Hindutva’ themselves abandoned it as they came close to power. Now they say: ”Development is the solution to all problems.”

In fact, save for the economic sphere, culture, education, and even internal security weakened under Indian rule. Various states deteriorated in their own way. Instead of a real concern, these too became little more than a slanging match between the leaders. When was the last time Parliament collectively thought constructively about any issue?

Also read: Blaming Macaulay for India’s failures is just lazy politics we’ve perfected since 1947

The merits of British rule

British rulers kept an eye on China, Russia, and even the Arab world from the perspective of British Indian interests. They made arrangements, intervened, and acted tough for national interest. Indian rulers, within a generation, mostly became incapable of seeing beyond their own Lok Sabha constituency! Many ministers considered nothing more important than showering favours on their constituency to secure their next election, and keeping the high command in good humour. Indian rule produced mostly such leaders for whom any ‘all-India’ concern was beyond their ken.

An assessment of the proceedings of Parliament and legislatures reveals what kind of discussions took place in the last fifty years—and what did not. Was there ever any deliberation on the collapse of communism, the spread of Islamic terrorism, the cleansing of Hindus from Kashmir, or the gradual academic deterioration in universities? The absence of any national policy on these matters was inevitable.

However unpatriotic this may sound, it was the British rulers who cared for the whole of India. They were the first to unite it politically—something that had never happened in known history! Then they created an integrated economic, monetary, judicial, educational, and a thorough internal-external security system for the entire country. Along with it, a sound administrative structure, with its training institutions, manuals of rules and regulations. This, too, had never happened in the known history of India.

Indian rulers adopted the British-created system in toto. They could not think any better. And they could not even maintain its quality. It deteriorated rapidly. It was no accident. Indian rulers lacked a really ‘national’ vision, loyalty to the higher purpose, a concern for the millions of citizens, and firmness that characterised British rulers. They were inexperienced in governance and warfare anyway. Hence proved unprepared for all contingencies that required a fighting spirit.

In addition, they also lacked the requisite self-respect that places responsibility & accountability above the desire to remain in office. Most Indian leaders regard staying in office as more important than fulfilling their responsibility. This was the exact opposite of the British rulers. Any British ruler would resign or be removed upon failure or a serious mistake. This practice quickly disappeared in Indian rule. It was institutionalised, even before taking the reins of governance, by the top Hindu leader, MK Gandhi, himself.

Thus, along with inexperience and lack of training in battle or governance, the prioritisation of personal interest by Indian leaders rendered governance practically dependent on fate. Most leaders—from Gandhi, Nehru to the present—have been fond of preachiness, imaginary ideologies, and pomp. They lacked a practical approach, sound judgement to match objectives with available means, commitment to state interest, firmness and self-discipline to uphold it—all that were normal features of British rulers.

Compare the Indian universities then and now. Everywhere, one can see a lack of standards and vision. Macaulay’s policy produced among Indians not only clerks, but also scholars, scientists, poets, and thinkers. Indian rulers had the tendency to treat even scholars and poets as clerks. The result was predictable: All the great literary, scholarly and scientific greats India produced were only during the British period.

It is telling, therefore, that even after eight decades of Independence, Indian leaders wail about Macaulay. It is nothing but a self-acknowledged incompetence. They could not devise a policy to supersede Macaulay. Therefore, denouncing colonialism is hollow. Their understanding of ‘national interest’ hardly goes beyond party interest. They use education and culture as mere instruments for it. Macaulay, the assistant of the Governor General Bentinck, was an influential poet and historian. Who have been the assistants of the Indian rulers?

By all indications, Indian rulers have been beating ‘colonialism’ and ‘Macaulay’ for show purposes. They live in past because they have little to offer for the present.

Shankar Sharan is a columnist and professor of political science. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

Of course, article from a product of the ecosystem..what else to expect?

The article essentially represents a strain of thinking that has been critiqued by postcolonial scholars like Frantz Fanon and Edward Said – where colonized subjects internalize colonial narratives and view their own culture and leadership through a colonial lens.