Centre-state relations are currently showing acute strain. Just last week, governors of three non-BJP-ruled states—Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Karnataka—walked out without reading, or reading only partially, the inaugural assembly speeches prepared by the state governments.

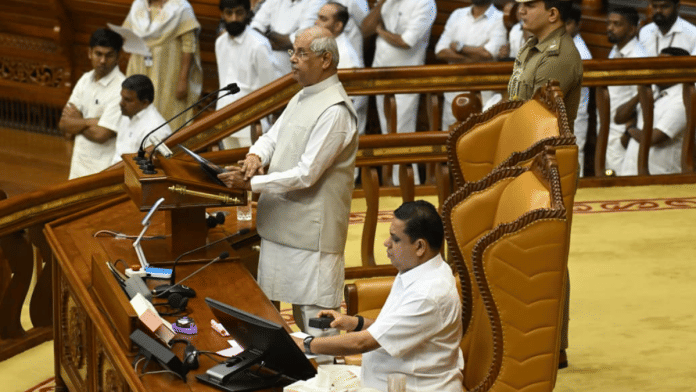

In Chennai, Governor RN Ravi walked out of the Assembly without delivering the speech on the ground that it was “laced with unsubstantiated claims and misleading statements”. In Thiruvananthapuram, Governor Rajendra Vishwanath Arlekar omitted parts of the speech which he wanted removed but had been retained in the text. In Bengaluru, Governor Thawar Chand Gehlot wrapped up what was to be a 43-page address in three lines and left. The speech had references to “injustice to the state in tax devolution and several other central schemes”, and was critical of the Centre for “repealing” MGNREGA.

Then, recently, there was a standoff between the Union government and the state of West Bengal over the alleged obstruction by Chief Minister Mamata Banerji, the state DGP, and the Kolkata Police Commissioner in the Enforcement Directorate’s probe in a PMLA case against the political consultancy firm I-PAC. The Supreme Court said it “raised a serious issue” relating to investigations by central agencies and “interference by the state agency”. It added that “larger questions are involved”, which if they stay undecided would “further worsen the situation” and lead to “lawlessness”.

“True, that any central agency does not have any power to interfere with the election work of any party. But if the central agency is bona fide investigating any serious offence, the question arises whether in the guise of taking shield of party activities, agencies can be restricted from carrying out duties,” the court said.

These events are not one-offs. Earlier, in Bengal, there were disputes over the role of the Governor, and the refusal of the state to grant general consent for CBI investigations there.

Tamil Nadu, too, has had an uneasy relationship with the Centre irrespective of which party ruled in New Delhi. In recent years, tensions have intensified over the imposition of NEET, perceived encroachments through the National Education Policy, and persistent delays by the Governor in granting assent to Bills passed by the state legislature.

Kerala presents another case of sustained friction. The state has challenged the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, objected to restrictions on its borrowing powers under the FRBM framework, and clashed repeatedly with the Governor over appointments in universities and delays in clearing legislation.

Punjab’s confrontation with the Centre during the farmers’ agitation against the now-repealed farm laws demonstrated another dimension of federal stress. The state government accused the Centre of bypassing the federal principle by legislating on matters affecting agriculture and markets, areas that are traditionally within the state domain.

India’s Constitution establishes a federal structure with a strong Centre, designed to preserve national unity while respecting regional diversity. Over the years, however, tensions between the Union government and the states have become frequent, and increasingly acrimonious. These recent developments point to a deeper malaise in India’s federal functioning. They raise fundamental questions about the balance of power, the role of constitutional authorities, and the future of cooperative federalism in India.

Also Read: Indian police need urgent reforms. 2006 SC order yielded no results

Causes of the federal strain

Several factors have contributed to this persistent confrontation. First, there is a growing trend of centralisation of power. While there may be some justification for it in the context of separatist and fissiparous tendencies in parts of the country, it is resented by the states. The Constitution provides for a strong Centre, but the excessive use of that strength, especially through central investigative agencies, has generated distrust among the states, particularly those ruled by opposition parties.

Second, the politicisation of constitutional offices has eroded conventions that once acted as informal safeguards. Governors, envisaged as neutral constitutional heads, are often perceived as agents of the Centre, interfering in legislative processes, delaying assent to Bills, or making political statements.

Third, institutional mechanisms for dialogue have weakened. The Inter-State Council, constitutionally mandated under Article 263 to resolve federal disputes, meets infrequently. As a result, political disagreements increasingly find their way to the judiciary.

Fourth, fiscal federalism has become a major fault line. States complain of shrinking fiscal space, conditional transfers, delayed GST compensation, and restrictive borrowing limits. Financial dependence accentuates political subordination.

Finally, there has been a steady erosion of constitutional morality—the unwritten conventions of restraint, accommodation, and mutual respect that are essential for a federal system to function smoothly.

Also read: Governor walkouts in Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka have turned ceremonies into conflict

Revive cooperative federalism

The Seventh Schedule of the Constitution places ‘police’ and ‘public order’ in the State List. Perhaps it is time to review the existing arrangement. Internal security has, over the years, acquired a new dimension. Terrorism, cybercrime, organised crime, and inter-state criminal networks do not respect state boundaries. Investigating these requires seamless coordination between the states and central agencies. The present arrangements often depend on political goodwill, which is not there in times of confrontation.

Madhav Godbole, a former Union Home Secretary, expressed himself strongly in favour of ‘police’ and ‘public order’ being shifted from the State List to the Concurrent List. Similarly, Fali Nariman, the noted constitutional expert, while addressing an annual meeting of the Indian Police Foundation, argued that just as ‘forests’ were brought from the State List to the Concurrent List to protect them from devastation, ‘police’ and ‘public order’ should also be moved in view of state governments blatantly misusing the police for partisan objectives.

However, transferring ‘police’ and ‘public order’ to the Concurrent List will be fiercely resisted by the states. It may be easier and more practical to place what the Second Administrative Reforms Commission called ‘Federal Crimes’ in its fifth report—terrorism, organised crime, major crimes with inter-state ramifications, acts threatening national security, serious economic offences, and the like—in the Concurrent List. That would allow for uniform standards, better coordination, and a more effective national response to emerging internal security challenges.

It is also essential to revive cooperative federalism in letter and spirit. The Inter-State Council should meet regularly, and major policy initiatives affecting states should involve prior consultation. The role of governors needs to be redefined in line with the recommendations of the Sarkaria and Punchhi Commissions. Fiscal federalism also needs recalibration.

Finally, constitutional conventions must be honoured. Frequent references to the judiciary are no solution. Political maturity, dialogue, and respect for the federal spirit are indispensable.

Centre-state confrontations undermine governance, politicise institutions and burden the judiciary. The answer lies in restoring trust, strengthening institutions and practising cooperative federalism.

The writer, a retired Director General of Police, has been campaigning for police reforms for the last three decades. His X handle is @singh_prakash. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)