The swearing-in of Tarique Rahman as Prime Minister of Bangladesh signals a new chapter in the neighbouring country’s history. His 17-year self-imposed exile in London coincided with the 17-year rule of Sheikh Hasina, the bête noire of Rahman’s mother and former prime minister Khaleda Zia. What began as a feud between Hasina’s Awami League and Zia’s Bangladesh Nationalist Party turned into an ego clash between two individuals.

For India, Rahman’s victory and the return of the BNP mark the end of nearly two decades of close ties with the Awami League, which had brought the two countries closer on several regional and security issues. Hasina’s sudden and forcible exit after the July Uprising took New Delhi by surprise and set in motion the process of sheltering her. As Hasina took refuge in Delhi and the BNP remained in disarray, Jamaat-e-Islami—a radical Islamist party that opposed Bangladesh’s 1971 liberation—took the lead in shaping public opinion in its favour.

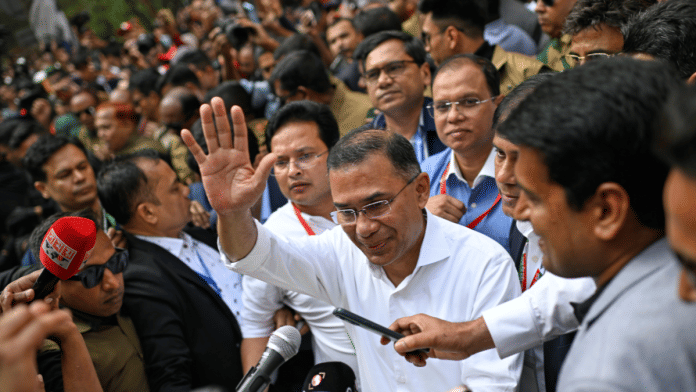

Rahman’s return after Zia’s death in December provided Bangladesh with a much-needed and acceptable alternative to the political chaos under the interim government led by Chief Advisor Muhammad Yunus. The BNP—founded in 1978 by Rahman’s father, General Ziaur Rahman—secured 209 seats in the 299-member Jatiya Sangsad (Parliament). New Delhi now has a window of opportunity to reset ties with Dhaka, which had deteriorated under Yunus as radical elements emerged.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s telephonic conversation with Rahman, and his statement that he is “looking forward to working with the new PM to strengthen our multifaceted relations and advance our common development goals,” signal a course correction in bilateral ties.

That said, both countries will have to take several steps and address key challenges before India-Bangladesh relations can return to the “good old days of bonhomie”. The new prime minister has been cautious in pressing demands for Hasina’s extradition but would expect India to restrain her political activities. New Delhi, which did not publicly engage with the BNP during Hasina’s rule, would do well to avoid overt displays of support for her party.

Similarly, Rahman could bolster his democratic credentials by lifting the ban on the Awami League and allowing it to resume legitimate political activity.

An unwanted legacy

Dhaka will have to deal with the burdensome legacy left behind by the Yunus administration. His foot-in-the-mouth statement on India’s northeastern states last year—“India’s landlocked Northeast faced the prospect of becoming an extension of the Chinese economy”—was followed up with mention of “seven sisters” and Bangladesh acting as their “guardian of the ocean”. These statements go contrary to what the new PM intends to do. If Yunus and his advisors wish to leave Bangladesh for good, Rahman should facilitate their exit with a big thanks.

Since 2017, more than a million Rohingyas have fled Myanmar’s Rakhine state following a military crackdown as a result of conflict with Buddhist settlements. Just as Bangladesh, India and China began dealing with the refugee crisis, several armed groups involved in drug smuggling and human trafficking infiltrated the refugee camps in Bangladesh and vitiated the atmosphere.

With increasing resistance from Myanmar’s military junta, dwindling international aid, and growing global apathy towards the crisis, the issue has become a persistent bone of contention. Meaningful negotiations can begin only after the restoration of normalcy in Myanmar and stability in Bangladesh.

Dhaka will need New Delhi’s support to contain further influx, manage the camps, and neutralise criminal networks. India, in turn, will have to tackle this challenge without inviting accusations of interference in Bangladesh’s internal affairs or eroding Myanmar’s trust.

Also read: Tarique Rahman’s first address as Bangladesh PM had 3 warnings

The Turkey challenge

Barely two days after Rahman was sworn in as prime minister, Bilal Erdoğan, son of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and German international footballer Mesut Özil landed in Dhaka for a scheduled visit to the Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar and to attend the first Iftar of Ramadan with the refugees. They also reportedly visited projects funded by the Turkish government.

Both New Delhi and Dhaka should remain alert and remember that Turkey’s expanding role in Bangladesh’s defence capabilities goes against India’s security and strategic interests, besides adding to regional imbalance. Both the BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami had promised to “build a strategic partnership” with Muslim-majority countries in their respective manifestos.

Earlier in February, Jamaat clarified that “strengthening relations with countries of the Muslim world shall be a key foreign policy priority”. A Turkey-Pakistan-China axis gaining a foothold in Bangladesh would significantly increase New Delhi’s discomfort even as it extends an olive branch to the new prime minister.

Dhaka urgently needs to stabilise its economy, and this can best be achieved through cooperation with India and through developmental projects centred around the Look-East-Act-East framework and the BIMSTEC platform.

An economically strong and politically stable Bangladesh will not only help the country come out of the present woes but also help in maintaining regional balance and contribute positively towards New Delhi’s efforts to build a strong South-South cooperation network.

Seshadri Chari is the former editor of ‘Organiser’. He tweets @seshadrichari. Views are personal.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)

The lure of money made India and Pakistan play cricket recently. Imagine the magnitude of money that can be generated by trade with Pakistan and Bangladesh. That money can be used to develop our economy and security.