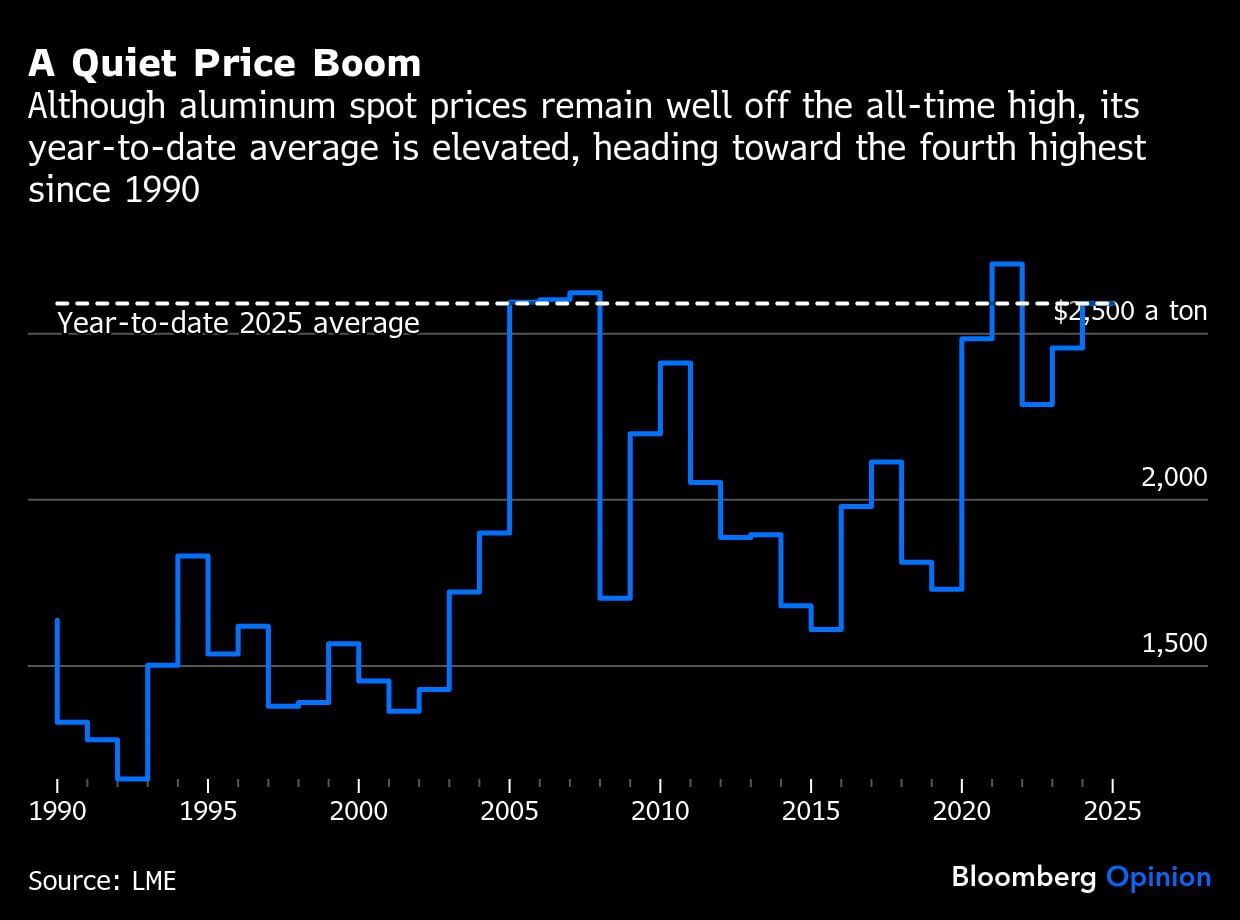

It lacks the effervescence of copper and the geopolitical allure of rare earths – yet aluminum is the metal of the moment. Key to modern life and everywhere in the global economy, it’s entering a make-or-break phase: Either the world is sleepwalking into a supply crisis or further into the hands of China. Or, more worryingly, both. The background is unsettling: Aluminum is trading at a three-year high, near $2,900 per metric ton. Although still far from the record, the current price is historically elevated, in the 5% top end of the 1990 to 2025 price range(1). Look at annual averages, and this year is heading to the fourth-highest ever.

With political leaders’ attention firmly on copper and the likes of germanium and rare earths, aluminum hardly attracts headlines. Still, it’s truly crucial for the global economy. Planes and iPhones, window frames and soda cans, electric cars and appliances all depend on it. One can hardly imagine any further electrification without the greyish metal. With an annual consumption value of nearly $300 billion, it’s the largest of all non-ferrous metals.

Only steel, a ferrous metal, is more widely used.Compared to other commodities, aluminum compounds such as bauxite are copious in the Earth’s crust. But producing the metal in its pure form used to be such so complex and expensive process that until a century ago it was considered a precious metal. Napoleon reserved aluminum cutlery for his most important guests. When the Washington Monument was completed in 1884 in the US capital, it was capped with a 100-ounce aluminum pyramid; at that time, the metal was more expensive than silver. Only two years later, a new refining system was invented, and aluminum become commonplace.

Still, there’s a catch. Producing aluminum is a massively energy intensive process, so much that the metal is often known as “solid electricity.” To produce a ton of aluminum, smelters require the same amount of electricity that five German homes would consume in a year.

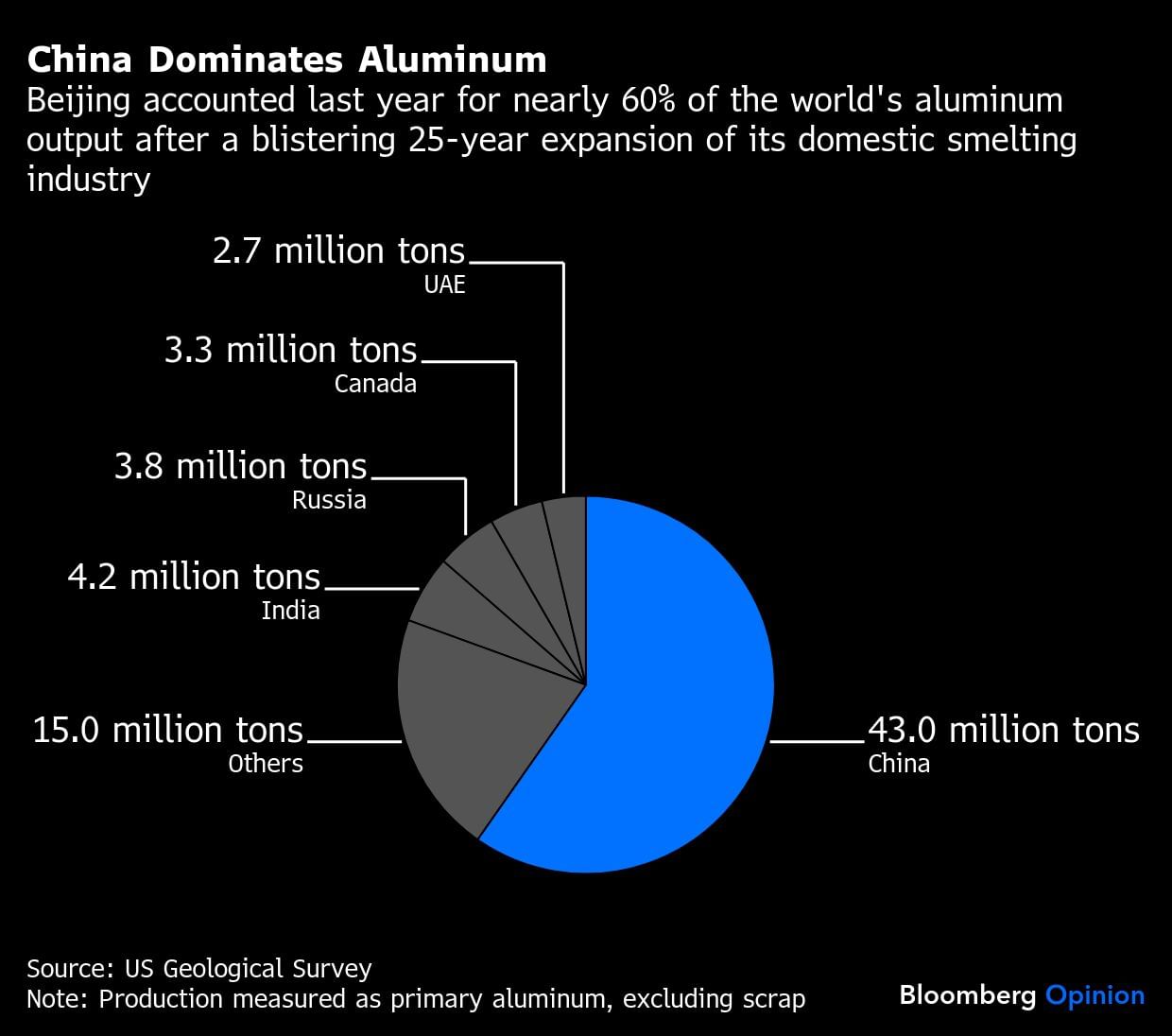

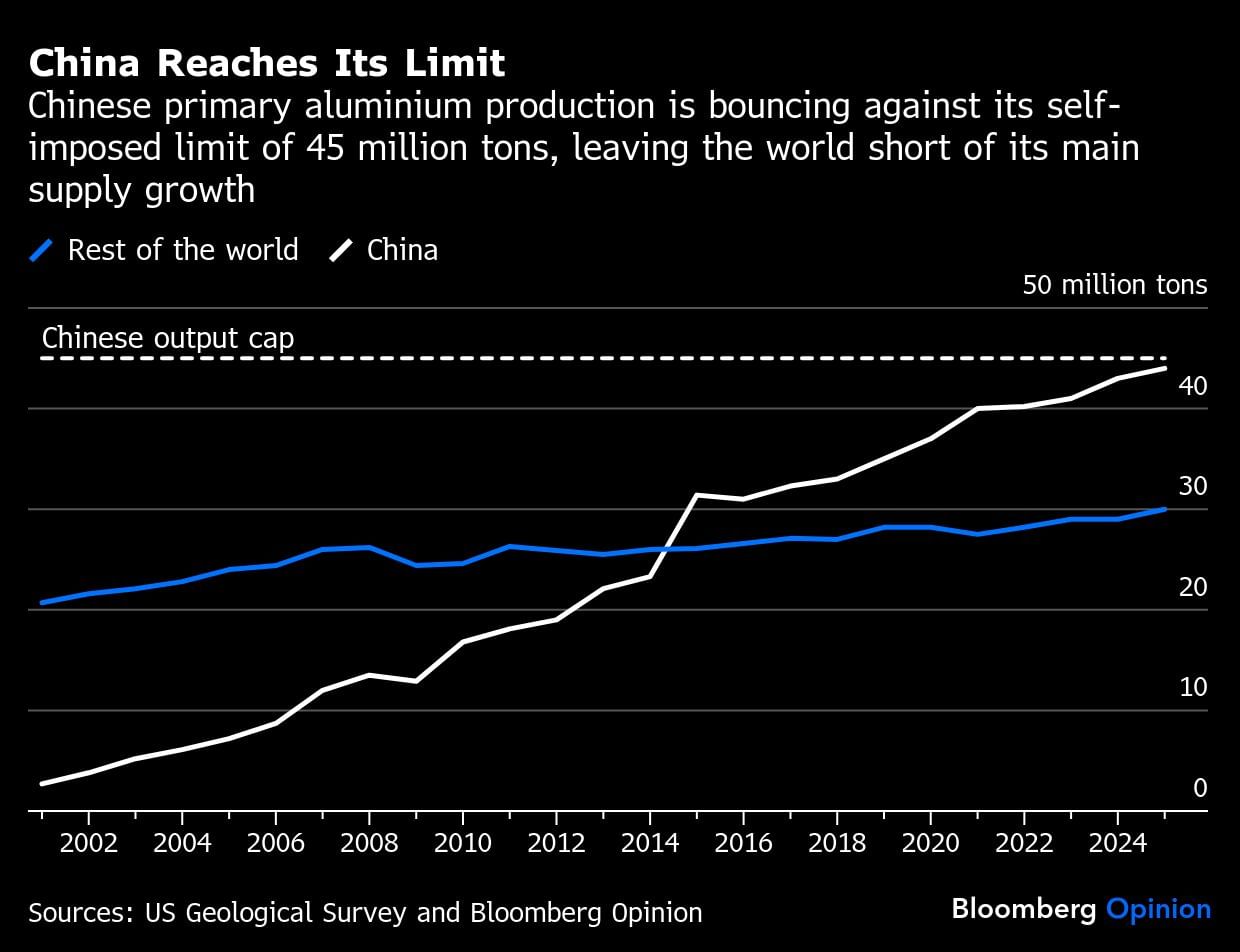

Enter China. Thanks to its coal-fired power stations, the Asian giant has the cheap electricity needed to produce enormous amounts of aluminum. Thus, for the last 25 years, Beijing has single handedly supplied the world’s incremental demand for the metal, which now runs just above 100 million tons(2). Last year, China produced just over 43 million tons of primary aluminum, up from 6 million two and a half decades ago. But its expansion is ending. A few years ago, the Communist Party capped its domestic smelter production at 45 million tons, and in 2025 local output is bouncing against the ceiling for the first time(3). By next year, it will hit it. What comes next is key.

The setting has all the elements for a squeeze. First, demand remains robust, rising every year by about 2-3 million tons. Second, production – notably in Europe – is struggling due to expensive electricity. Despite high aluminum prices, smelters are shutting down in many countries as long-term cheap electricity contracts end. Third, global inventories are historically low.

And fourth, with copper prices at an all-time high, there’s a clear incentive to substitute the red metal with aluminum wherever possible.Unless incremental supply comes from somewhere or an economic crisis cuts consumption, something will have to give. The market is bitterly divided. The bulls see aluminum sleepwalking into structural shortage, with prices climbing toward a record high of $4,000 in a couple of years; the bears anticipate that Chinese companies would manage to produce more, and aluminum would ultimately trade lower.

The key is Indonesia, where top Chinese companies are now erecting the smelters they can’t build at home due to the cap. With plentiful coal, cheap labor, copious aluminum feedstock and little regard for climate policies, Indonesia is now a construction site for the likes of Tsingshan Holding Group Co., China Hongqiao Group Ltd. and Shandong Nanshan Aluminum Co. It echoes a similar Chinese move in the nickel market a decade ago and that transformed Indonesia into a top producer.

If all the new smelters come into production, Indonesian output may rise fivefold by 2030, transforming the country into the world’s fourth-largest producer, behind only China, India and Russia, and keeping the global market well supplied. On top, Chinese companies are also building aluminum smelters in Angola, using hydropower as their electricity source. But past performance in nickel does not guarantee future results in aluminum.For one, the cost of building an aluminum smelter in Indonesia appears to be higher than in China, slowing down the expansion. And the Chinese companies aren’t bringing into Indonesia a technological advance that would change the metallurgy of aluminum in the same way they did for nickel.

Indonesia clearly would become an important supplier – but it’s far from certain that alone it can replace the role that China has played since 2000 balancing the market.For the bulls, the bigger risk is that Beijing caves and lifts the cap – or creates enough loopholes. For example, China could exclude smelters running on green electricity, including those using hydropower, from the ceiling. Or it can allow existing plants to run harder, pushing up electricity flows without physically expanding the production lines.The world faces a binary outcome: Either higher aluminum prices, spilling over the global economy, or a higher reliance on Chinese companies. Perhaps there’s a third outcome – and one that I think is most likely: We get higher aluminum prices but perhaps not as exuberant as the bulls are betting on, while Chinese output, via Indonesia, also increases, but not as much as the bears hope.

(1) In more than 8,000 trading days since 1990, benchmark aluminium has only traded above current levels for about 250 days.

(2) Global supply is composed of two streams: so-called primary metal, produced in smelters, accounting for about 72 million metric tons last year, and scrap, or recycled metal, which is produced in normal ovens which require far less electricity. The amount of scrap recovered every year varies depending of prevailing prices, but in recent years it has topped 30 million tons. Aluminium is one of the most recycled materials on earth, with about 75% of the metal produced recoverd.

(3) China introduced the cap in 2017 after a huge annual increase in smelting production capacity and an effort to both improve the industry’s profitability and rein in electricity consumption.

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Javier Blas is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. He is coauthor of “The World for Sale: Money, Power and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources.”

Disclaimer: This report is auto generated from the Bloomberg news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.