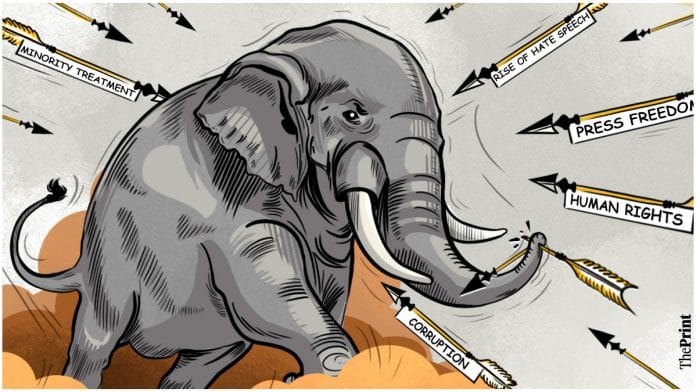

The government’s prickly responses to international commentary on the country’s press freedom, human rights, corruption, treatment of minorities, etc reveal a blunt unwillingness to accept a deteriorating situation on most such issues.

Any independent observer can see that media freedom has suffered under the Narendra Modi government. It is equally obvious that the regime has facilitated the creation of a public space that has given rise to hate speech (like public calls for lynching Muslims), the overwhelming of the social media by hostile troll armies, street killings, and the like. None of this is news to Indians, who don’t need international ratings to tell them what the reality is.

What bears noting are the government’s different responses to criticism. Domestic criticism is treated with a combination of disdainful silence, off-camera pressure, curbs on the right to information, action under draconian laws, and prosecutorial action where the process becomes the punishment. Such disdain is altogether missing in the responses to criticism from overseas. What is on display then is a defensive aggression typical of quasi-autocracies. This betrays a sensitivity to international (usually Western) opinion, however much that may be denied.

Where the government and those speaking for it have a valid point is when it comes to India’s place in global rankings, many of which show India performing worse than it actually does. When Reporters Without Borders says that press freedom in India is less than in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, the loss of credibility is not India’s but that of the organisation doing the ranking.

When India is shown to have a high level of stunting (i.e. low height for age) among children, it is as well to point out that the benchmarking of what normal is has no Asian countries (where people tend to be shorter than Europeans or some Africans) in the sample.

Similar deficiencies have been pointed out with regard to rankings on democratic credentials. Even with credit ratings, India has had a long-term issue with how it is classified. Today, the US government (fighting yet another Congressional battle over the debt ceiling) is more likely to default on payment obligations than India’s government. And when it comes to rankings on competitiveness, it is notable that the fastest-growing economies, or those with the fastest export growth, are never ranked as among the most competitive.

One could reasonably argue that these reflect either defective methodologies or plain bias. That facilitates sweeping denialism as a response, and assertions that the global powers are hostile to India’s rise.

The facts on this last are plainly to the contrary. Especially in the context of a rising China, almost the entire Western world and key countries in the Asia-Pacific region welcome India’s growing strengths. Besides, India’s global ranking on corruption might improve if contractors and others did not talk in Karnataka about 40 per cent commissions demanded by politicians.

The Western conceit lies in the questionable binary that some markets are “emerging” while others have presumably “emerged”. Anything that goes wrong in the former provokes comment about “systemic” defects. Not so with an emerged economy where anything that goes wrong is merely an aberration, a departure from the norm.

Naturally, one can’t be blind to India’s systemic imperfections: Gautam Adani as an example of the business-politics nexus, and the IL&FS collapse as a pointer to the failings of managements, auditors, rating agencies, and regulators. But was the financial crisis of 2008 any less of a systemic American failure — of big banks, insurance companies, regulators and lawmakers?

Consider how regional American banks are toppling over like dominoes. Or the lies told in British politics that led to a suicidal Brexit. And the rigging of the London inter-bank money market, part of the continuing flow of scandal: Credit Suisse, Wirecard, FTX, Deutsche Bank, and Volkswagen, quite apart from the late pedophile Jeffrey Epstein’s connections to top-level bankers.

And which are the banks that hurried to limit their risk in the wake of the Hindenburg Research report on Adani? Barclays, Citibank, and other storied names. But it is only “emerging” India’s systems that are weak?

Everyone needs to look in the mirror, prickly India included.

By special arrangement with Business Standard.