Where is it cheaper to buy rice? At a village market in India, a country where 377 million people live below the poverty line? Or on the trading screens of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange?

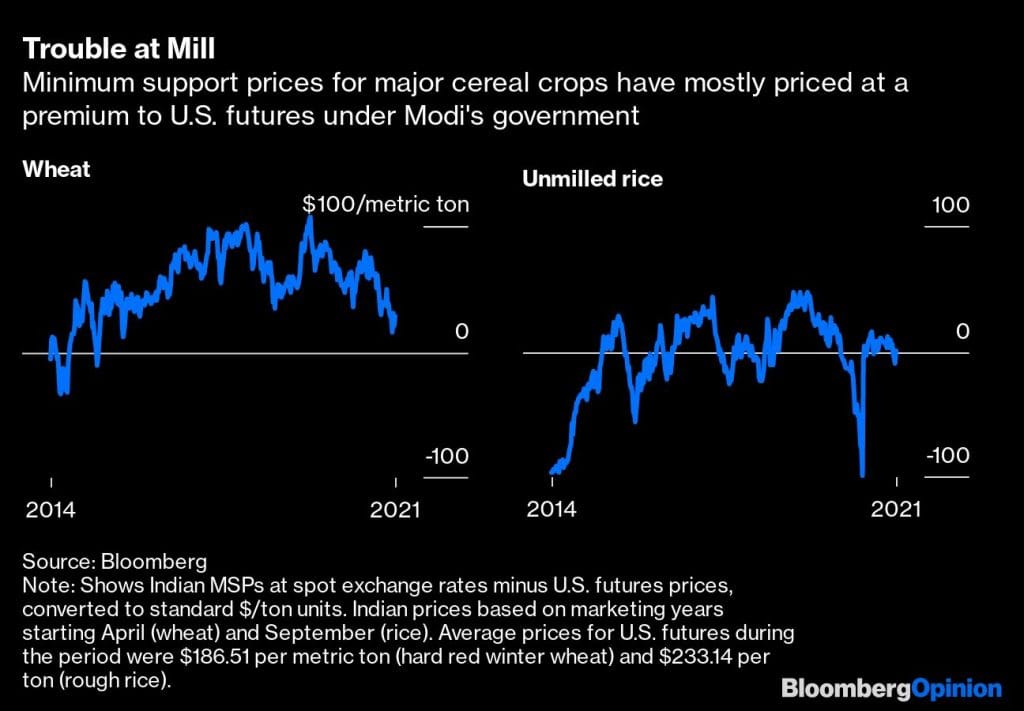

Shockingly, it’s often the latter. Rough rice futures on the CME averaged $12.63 per hundredweight since the start of September and traded as low as $11.85, equivalent to about $233 a metric ton. Meanwhile, the minimum support price at which India’s government buys unmilled rice from farmers has been fixed at 1,868 rupees per quintal in the same marketing year, or $254 a ton at average exchange rates.

The gap is even wider for wheat, whose minimum support price has averaged a 25% premium to soft winter wheat futures in Chicago in the current marketing year:

That disparity stems from distortions. Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of post-colonial India, repurposed Soviet state planning for a democratic setup, and from 1956 invested heavily in sectors that made machines to produce industrial goods. By the mid-1960s, though, it became apparent to Nehru’s successors that a shortage of basic consumption items — mostly farm output — was getting in the way of hiring and paying India’s abundant labor. That’s when minimum support prices came into being, as a way to coax farmers to feed a rapidly growing population.

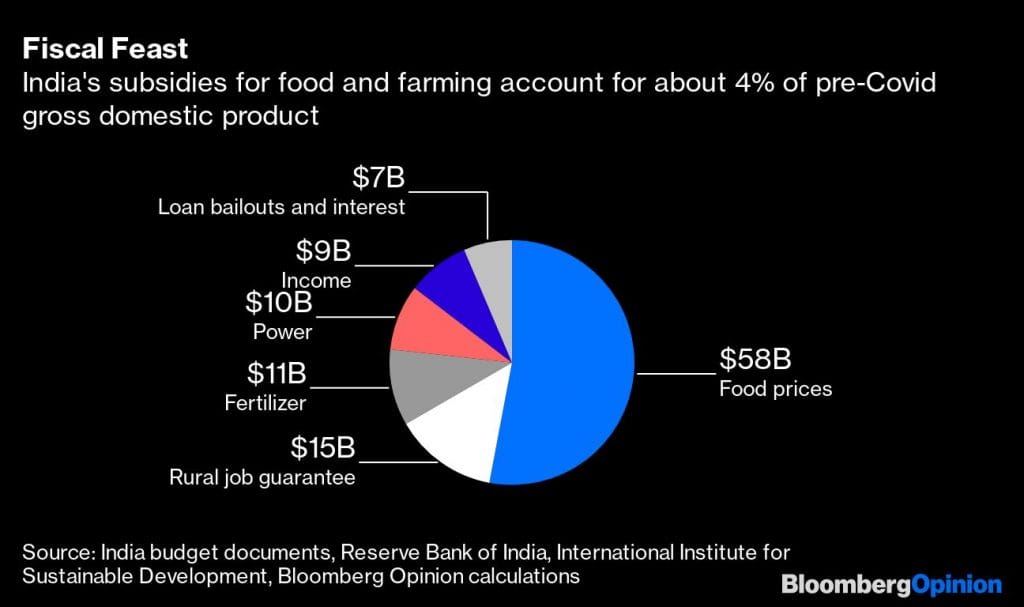

But in a poor country, high prices assured to growers can’t be passed on to consumers. When both are subsidized, the cost can be as high as 4.2 trillion rupees ($58 billion) in a pandemic year — and even half of that otherwise. Also, nine out of 10 farmers who own less than five acres have been largely left behind by post-1990s reforms that have widened the productivity gap of non-farm labor over agricultural workers to 5.5 times, among the highest in the world.

More than three-fifths of the 1.3 billion population is stuck on the farm, and kept there with a $11 billion fertilizer subsidy; $9.5 billion in unmetered electric power; about $4 billion annual expenditure on periodic loan waivers; and of late an $80-a-year income supplement, which adds up to $9 billion. For the landless, there’s a rural job guarantee, which cost $15 billion after migrant workers lost their urban jobs to the Covid-19 lockdown and returned to their village homes.

Also read: Farmers not aiming at any change in power but solution to their problems, Rakesh Tikait says

Viewed in this context, protests against new agricultural laws by farmers amassed at New Delhi’s borders are the long overdue birth pangs of a more urbanized nation. The reforms that are making farmers anxious have been deliberated since the early 1990s. When it comes to making them palatable, the missing ingredient even now is skilled midwifery: Farmers need to be able to trust both the intent and execution capacity of political leaders to fashion a new deal with taxpayers and consumers. It’s not enough to say that giving a free rein to markets will automatically make India’s farmers productive and prosperous. Someone has to explain what new organizational arrangements will replace the extensive state support that exists today.

A new bargain with farmers is needed for India to have a shot at reclaiming past glory. In 1750, the Mughal Empire accounted for about a quarter of the world’s industrial output, and cotton textiles from Bengal and Kerala were traded worldwide.

Imperialism and the British industrial revolution devastated that trade. Britain’s higher wages for textile workers forced its mills to adopt inventions such as the spinning jenny and flying shuttle to compete with Indian cloth. Protected by tariffs on Indian imports, the productivity of these technologies quickly became so great that the Lancashire textile industry was able to reverse the inherent disadvantages of more expensive labor and raw materials. Labor costs per unit went from more than double those in India in 1770 to less than a third in 1820, impoverishing India, which was reduced to being a supplier of commodity cotton to its colonial overlords.

It’s unlikely any of this would have happened had it not been for the rapid and early decline of England’s rural workforce. By the mid-18th century, agricultural employment already accounted for not much more than a third of the total. As a result, the country hit its Lewis turning point — the moment when excess rural labor supply is soaked up, resulting in wage rises that eventually improve the productivity of both urban and rural businesses — earlier than anywhere else on the planet.

That moment is finally coming near in India, too. As a share of total jobs, farming is about to drop below the 40% levels at which so many other countries saw growth take off. That feeds into the food price debate. A decade ago, when most Indians worked in agriculture and were more likely to be sellers than buyers of food products, it made sense for the government to prop up prices in what’s known as mandi markets, and seek to manage the cost of urban living with consumer subsidies. A kilo of rice, which has an economic cost of 37 rupees to the taxpayer, is sold to two-thirds of the population for 3 rupees.

It’s an unsustainable equilibrium. Instead of overemphasizing heavy industries like steel-making in the 1950s, if India had adopted an indigenous model that had advocated creating surpluses in so-called wage goods — rice, tea, everyday cotton clothing, matchsticks and so on — those extra earnings of rural and semi-rural households could have spread incomes more widely and laid a more solid basis for industrialization and urbanization. The $100 billion-plus being spent annually on subsidies and income support could have been redirected to infrastructure, services like healthcare and education, and perhaps a basic minimum income for all.

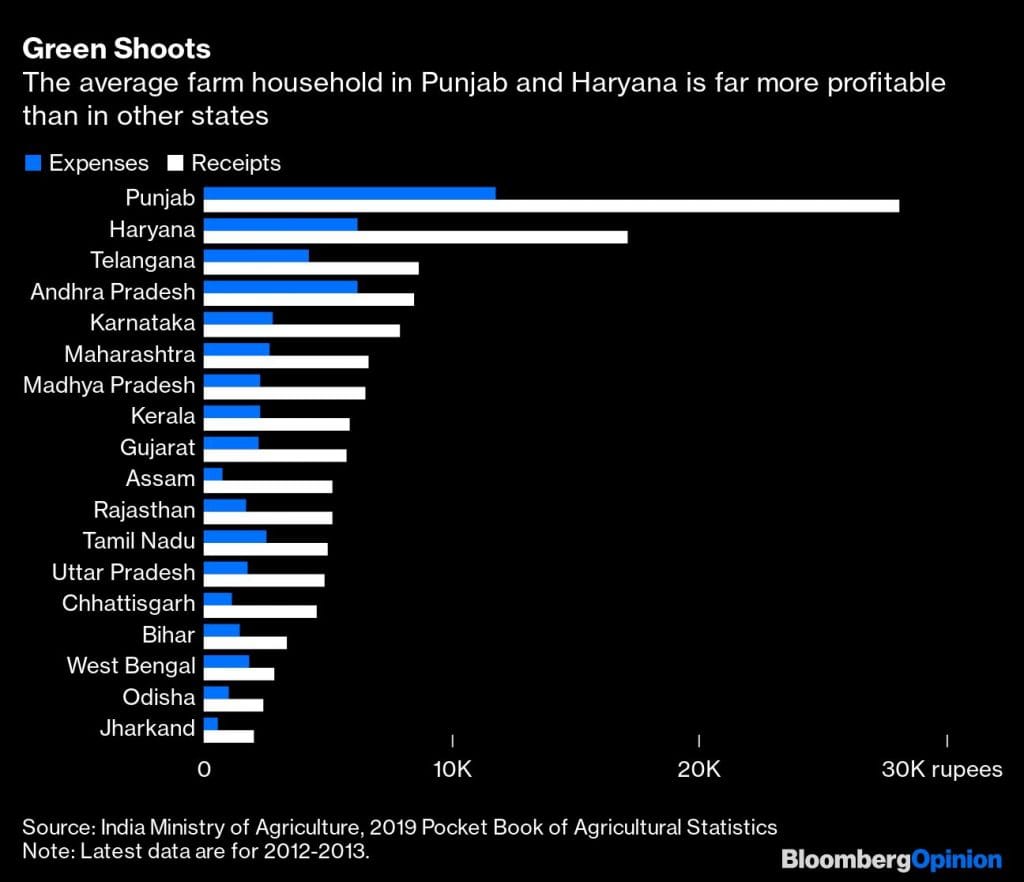

The mandi system has certainly benefited a class of farm workers, especially in the northern grain basket states of Punjab and Haryana. In many ways, those states have the most sophisticated farming industries in all of India, with the highest share of land under irrigation, the highest incomes from crops, and some of the lowest levels of rural poverty.

But paying each of Punjab’s 1 million farmers $1,600 a year in subsidized fertilizer and free power to pump groundwater is a drag on the economy and the ecology. In farm productivity, the states that have diversified beyond rice and wheat — the only two commodities for which minimum support prices really matter — are far ahead. Punjab, meanwhile, is sitting on depleted aquifers and environmentally unsustainable cropping patterns. Hazardous pollution in northern India is hurting the urban poor.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government has tried to introduce reforms by stealth, saying that the mandi or the minimum support prices aren’t going anywhere. Farmers, he says, will have more choices of private buyers; they will earn better prices. However, Punjab’s cultivators can intuitively guess that their 1960s bargain with the state is ending. The powerful arhtiyas, or aggregators who bring crops to the mandi, know that their commissions would wither away.

That, too, has its parallel in the history of the industrial revolution. Britain’s landed gentry sought to protect its wealth and prerogatives by demanding high tariffs and bans on grain imports, resulting in the Corn Laws imposed from 1815 to 1846. Those laws got repealed only after manufacturing-led urban interest groups became powerful in their own right, helping tilt the balance.

In India, a pushback to farm reforms was expected because of the manner in which the laws were rushed through parliament. Modi supporters are making the unrest worse by branding Punjab farmers as Sikh secessionists. The West, which has always complained about Indian farm subsidies at the World Trade Organization, can’t but be supportive of pro-market reforms. But cutting off internet access at protest sites has ignited a rebuke from the U.S. State Department. Pop star Rihanna and climate activist Greta Thunberg have internationalized the agitation. Delhi has been barricaded with barbed wires. The space for a compromise is shrinking, and that’s a shame.

A year before his death in 1964, Nehru was getting tired of relying on food aid from America that was given without much grace, and received without much gratitude. “If we fail in agriculture,” he said, “it does not matter what else we achieve — how many plants we put up — our economic development will not be complete.” That’s true even today. Although the two leaders couldn’t be more dissimilar, if Modi can manage the crisis honestly, modern India may finally grasp the industrializing vision of Nehru.- Bloomberg

Also read: How farmers’ protest has made Haryana khaps, infamous for honour-killing diktats, relevant again